A Strategic Foresight and Warning Issue for National Security

In the light of the 31 january 2012 “Unclassified Statement for the Record on the Worldwide Threat Assessment of the US Intelligence Community for the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence” by James R. Clapper Director of National Intelligence, which identifies Water Security in the chapter on Significant State and Nonstate Intelligence Threats (p.29), this is an updated version of a post initially published on The Water Chronicles, December 8, 2011.

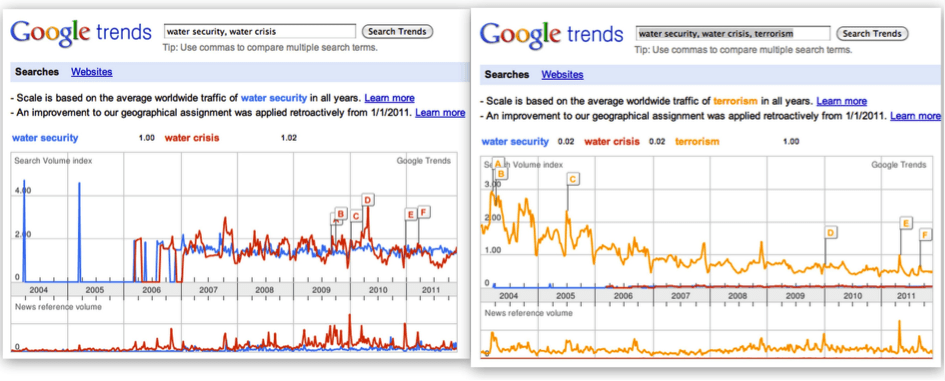

The emergence of a global water crisis seems to be a fact that is reaffirmed across actors almost everyday, even if the overall web worldwide traffic devoted to the topic is still marginal compared to terrorism for example, as shown by the two graphs below.

Witness to this double characteristic of importance and relative lack of awareness, the National Geographic, for example, in 2005, had a whole section devoted to the water crisis or more precisely freshwater crisis to contribute to raise interest: the National Geographic’s Freshwater Initiative. It remains (2021) as The Freshwater crisis.

This global water crisis would spare no country, from the most powerful, as underlined again in the December 4, 2011 Tomgram: William deBuys, The Parching of the West for the U.S. to richer ones such as Singapore, for example, which faces a “lack of natural water resources.” Meanwhile Mapelcroft identifies in 2011 Bahrain, Qatar, Kuwait and Saudi Arabia as “the most water-stressed countries in the world,” – each ranking respectively in terms of wealth, 3rd, 34th, 1st, 14th, 41st, IMF 2010. Emerging countries are not spared: for example, India faces many water problems from pollution to water depletion, while poorest countries sometimes face further desertification. This wide and unremitting geographic scope also further questions the fading developed-rich/developing-poor countries cognitive model inherited from both the self determination period and the three-worlds Cold War world view, asking from us to revisit our perceptions if we are to understand contemporary challenges and crises and ever hope to solve or more modestly mitigate them.

Meanwhile, various related research programs in universities and think tanks throughout the world have been developed. As indication, Academia.edu references 100 programs, 53 universities and 39 academic journals focused on water. Among others, since 1991 a World Water Week has been organised, initially by the Stockholm Vatten AB, the municipal water and wastewater provider, on behalf of the City of Stockholm (SIWI, history). It led to the creation of the Stockholm International Water Institute in 1997. According to its organisers the World Water Week has become “the annual focal point for the globe’s water issues.”

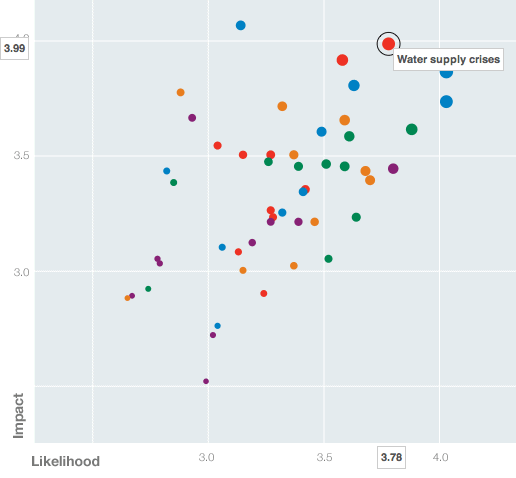

Furthermore, water related risks have been identified by the Global Risks Reports of the World Economic Forum (WEF – Davos) under one label or another since 2007. The 2012 Global Risks Report underlines the severity of the water threat, which belongs now to the top 5 risks: water supply crises rank 5th in terms of likelihood, and 2d in terms of impact. An encompassing “water security” had been already singled out in the 2011 Global Risk Report as “the top 10th risk by likelihood and impact combined.” The risk was deemed to be not only very likely but also to have a perceived impact approaching 500 billion USD. Compared with the 2010 perceived impact (then for water scarcity – risk 22 – and not water security) the perceived impact skyrocketed from an estimate of less than 40 billion USD.

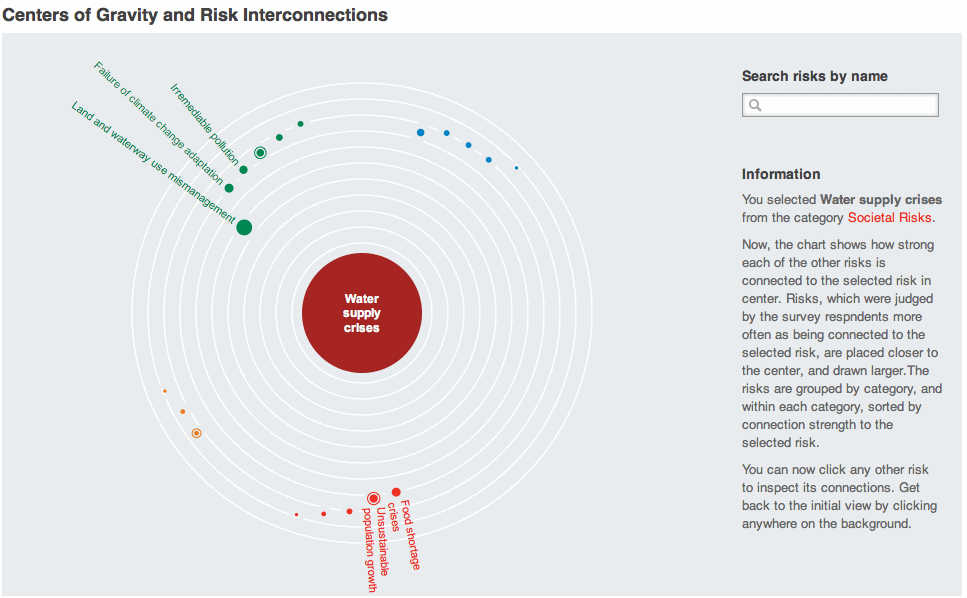

Furthermore, in 2011, the water security risk is seen as interconnected with eight other risks and in 2012 water supply crises are linked to nineteen risks, as shown on the figures realised thanks to the very interesting interactive way the reports are presented online. The water-food-energy risk nexus is amply detailed in the 2011 report and benefits of a specific initiative: http://www.weforum.org/water. Water is on the Agenda of the Global Councils of the WEF since 2008.

Meanwhile, and as expected from the interconnections shown by the Global Risks Report 2011, water is widely seen as a cause of strife and conflict, as recalled by a recent New York Times blog by Rachel Nuwer, “The power politics of water struggles,” focusing notably on the idea of hydro-hegemony, a framework for analysis of trans-boundary water conflicts, conceptualized by the Canadian Dr Mark Zeitoun of the University of East Anglia. As explained in an article by Zeitoun and Warner, “Hydro-hegemony is hegemony at the river basin level, achieved through water resource control strategies such as resource capture, integration and containment. The strategies are executed through an array of tactics (e.g. coercion-pressure, treaties, knowledge construction, etc.) that are enabled by the exploitation of existing power asymmetries within a weak international institutional context” (2006).

Indeed, the Water and Sustainability Program of the Pacific Institute, in its World Water Conflict Chronology Map presents an exhaustive chronology of 225 water conflicts displayed on an interactive map, showing both their global historical and geographical scope. Conflicts identified in the project start with the c. 3000 BC deluge also told by Sumerian myth, which underlines another potentially crucial dimension of the water issue, its relation to myth, symbolism and the sacred, within a larger cultural dimension as specified on other grounds by Roberto Melville and Claudia Cirelli (2000). The last updated conflict relates to 2010 violent water protests in India thus showing the influence of water on domestic issues, while more conventional disputes with potential for escalation and war are not forgotten, with the example the India-Pakistan Indus dispute (1947-1960s).

We thus have present as elements of this global water crisis: wars and perception of foreign enemies, break down of order and protests, threat to food security, and more generally life, as well as symbolic and customary meaning. Those are nothing else than potential and emergent symptoms that could lead to failure to ensure security, which is the mission of the ruler. Indeed, Moore (1978, 22) “defines the mission of security of authorities as comprising three elements: protection from foreign enemies, foreign being defined by what does not belong to the sphere of the ‘we,’ maintenance of peace and order, and contribution to ‘material security,’ or ‘security against supernatural, natural and human threats to the food supply and other material supports of customary daily life’” (Lavoix, 2010). As we still live, for the great majority, in nation-states, this security is nothing else than national security (conventional security tends to refer to strictly military matters, while unconventional security is being used for any other relevant issue).

To avoid such security failures that would not only have direct dire consequences but also impact in terms of legitimacy, rulers (andmore boradly all actors that could be impacted or are players) have at their disposal a process and analytical tool that helps them anticipating uncertain changes and thus preventing them, mitigating them at best or taking advantage of them when theose changes are opportunities. This process is called Strategic foresight and warning (SF&W). It “is an organized and systematic process to reduce uncertainty regarding the future (Fingar, 2009). It aims to allow policy-makers and decision-makers to take decisions with sufficient lead-time to see those decisions implemented at best (Davis; Grabo 2004; Knight, 2009). It must thus helps us in identifying the frontiers of plausibility within which changes in our surroundings are most likely to take place within a specific period of time, so that we can best coordinate our activities for our society’s security, in the light of those coming alterations” (Lavoix, 2011).

———-

References

Davis, Jack, “Strategic Warning: If Surprise is Inevitable, What Role for Analysis?” Sherman Kent Center for Intelligence Analysis, Occasional Papers, Vol.2, Number 1, accessed June 28, 2010.

DeBuys, William, Tomgram: William deBuys, The Parching of the West, Tomdispatch.com, December 4, 2011.

Fingar, Thomas, “Anticipating Opportunities: Using Intelligence to Shape the Future,” and ”Myths, Fears, and Expectations,” Payne Distinguished Lecture Series 2009 Reducing Uncertainty: Intelligence and National Security, Lecture 3 & 1, FSI Stanford, CISAC Lecture Series, October 21, 2009 & March 11, 2009, accessed June 28, 2010.

Government of Singapore, PUB Singapore’s National Water Agency.

Grabo, Cynthia M., Anticipating Surprise: Analysis for Strategic Warning, edited by Jan Goldman, (Lanham MD: University Press of America, May 2004).

Knight, Kenneth, “Focused on foresight: An interview with the U.S.’s national intelligence officer for warning,” McKinsey Quarterly, September 2009, accessed June 28, 2010.

Lavoix, Helene, “Enabling Security for the 21st Century: Intelligence & Strategic Foresight and Warning,” RSIS Working Paper No. 207, August 2010.

Lavoix, Helene, Ed. Strategic Foresight and Warning: Navigating the Unknown. Singapore: RSIS-CENS, 2011.

Mapelcroft, “Maplecroft index identifies Bahrain, Qatar, Kuwait and Saudi Arabia as world’s most water stressed countries: Key emerging economies and oil rich nations export water issues to ensure food security through African ‘land grab’,” 25/05/2011.

Melville, Roberto and Cirelli, Claudia, “LA CRISIS DEL AGUA. Sus dimensiones ecológica, cultural y política.” (LA CRISE DE L’EAU. Ses dimensions écologiques, culturelles et politiques), Memoria # 134 en abril del año 2000; further translations.

Moore, Barrington, Injustice: The Social Bases of Obedience and Revolt, (London: Macmillan, 1978).

National Geographic, National Geographic’s Freshwater Initiative.

Nuwer, Rachel, “The power politics of water struggles” New York Times blog, 28/11/2011.

Pacific Institute, World Water Conflict Chronology Map

Stockholm International Water Institute, “History”

The World Economic Forum,

- World Economic Forum Global Risk Report 2006.

- World Economic Forum Global Risk Report 2007.

- World Economic Forum Global Risk Report 2008.

- World Economic Forum Global Risk Report 2009.

- World Economic Forum Global Risk Report 2010.

- World Economic Forum Global Risk Report 2011.

- World Economic Forum Global Risk Report 2012.

Wikipedia, “List of countries by GDP (PPP) per capita.”

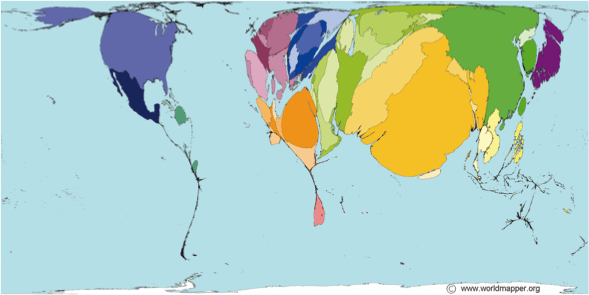

World Mapper, “Water Depletion Map,” Water series, Map 323,

Zeitoun, Mark, and Warner, Jeroen, « Hydro-hegemony – a framework for analysis of trans-boundary water conflicts,» Water Policy Vol 8 No 5 pp 435–460 © IWA Publishing 2006 doi:10.2166/wp.2006.054.