Farmers’ protests have spread throughout Europe (notably France, Germany, Hungary, the Netherlands, Poland, Romania…) since at least mid-2023 with escalation at the start of 2024, as well as in India although for different reasons. In this light, we republish two articles that address the issue of protests and how they should or could be answered.

The first article explains how and why protest movements spread, through which dynamics. This article is the second part and focuses on the role of governments and political authorities in stabilising or escalating movements. It locates protests movements in a larger more encompassing dynamic that is at work since at least 2010.

This article seeks to show how to assess the future of a protest movement with the example of the Yellow Vests and of the situation in France in 2018-2019. It looks at the way the actions of political authorities can stabilise a protest movement. Then it applies this understanding to the French movement. It can be used and applied for other protest movements, such as the farmers’ movements of 2023-2024.

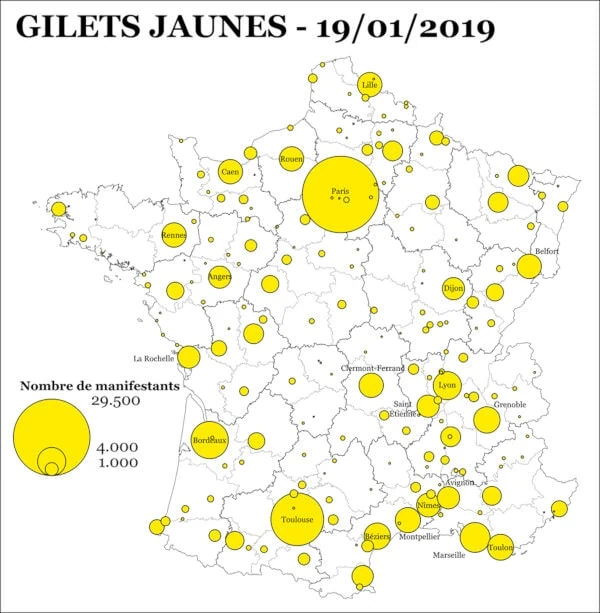

Indeed, if protests in France continue, Saturday 26 January 2019 would have seen a decrease in mobilisation. According to the much debated figures given by the French Ministry of Interior, the number of protestors involved went from 287 710 people (17 November 2018), to 84 000 (19 January 2019) and 69 000 people (26 January), i.e. minus 17.85% in one week. Alternatively, the movement itself tried to develop its own way to count the participants, “Le Nombre Jaune“. The figures here went from 147 365 people on 19 January to 123 151 on 26 January, i.e. minus 16.43%.

Thus are we in a stabilising process?

Needless to say, the impact of a revolutionary France would be huge. Indeed, France has a permanent seat at the UN Security council, and is the 6th largest economic power (Business Today, 22 Nov 2018). It also has a crucial place and weight in the EU. It is thus imperative for all actors to closely monitor the events in France. Indeed, the basic rule of risk management or strategic foresight is to pay attention to high impact events, even if the probability to see such an event taking place is low (below 20%). And, in the case in France, as we shall show below, this likelihood is not that low, even if it is not highly probable (above 80%) either.

This article builds on a first part, where we focused on the birth and spread of a protest movement. It uses knowledge obtained from the past to decrypt the present and the future.

The Yellow Vest movement is part of a wider pattern of protests, which has been spreading globally since 2010. As we expected when we started monitoring these dynamics, the current global protest movements spreads, multiplies and recurs. Thus, globally, the situation is escalating. Nonetheless, each movement also displays its own idiosyncrasies, while it learns from previous protests. For each protest, when the political authorities do not stabilise the movement from the start, then the situation becomes escalating. This is exactly what has been happening so far in the French case.

In this article, we are thus concerned with national or country-wide protests. We first point out that the initial blind response of political authorities is escalating. Then we identify three stages that “rulers” can follow to stabilise a movement. For each stage, we assess the French situation, what needs to be monitored and briefly outline possible futures.

Blind first response: escalating a protest movement

As previously, to identify the phases of responses of the political authorities, we use the past case of the 1915-1916 peasant movement in Cambodia. That protest involved up to 100.000 people, which represented approximately 5% of the population. In the case of France, 5% would mean that approximately 3 million people would be in the street.

Then, the political authorities initial feedback actions occurred as soon as the movement appeared, in November 1915. They were not stabilising but escalating, as they did not end the protest but, on the contrary, increased it. Indeed, the answers dealt with only one part of the multiple motivations for escalation. They only considered the 1915 prestations (corvées) and ignored all the issues that created the rising inequalities, as well as the related resentment and feelings of injustice. The response then was built upon a complete lack of understanding of the situation. Furthermore, they incorporated the belief in a potential plot, rather than considering the real causes for grievances.

We had a similar dynamic in France. The timing is, however, worse for the French political authorities (references at the end of the article). When the first protest took place on 17 November, the government hardly reacted until 4 December 2018. Despite these three weeks, the French political authorities did not take the measure of the problem. The Prime Minister only answered on the trigger of the protest, the oil tax. He ignored all other demands, which the process of demonstrating without answer revealed. Note that the French protestors’ demand are, in essence, very similar to those expressed in 1915 in Cambodia.

The Cambodian case shows that stabilising actions must be related to the reasons for escalation. Furthermore, it points out that partial solutions are not stabilising. The French case confirms this finding. As a result, what is crucial is understanding the protest movement. The 1915 belief in a plot also underlines the difficulty to obtain a realistic analysis, when one is prey to biases and when one does not have time to reflect but must act immediately. In the French case the situation indeed looks worse as, despite an absence of immediate reaction, understanding did not improve. The French political authorities may not benefit from a proper monitoring system or from a proper analytical framework to understand what is happening. This could be inherently escalating.

Stabilisation phase 1: Listening and immediate feasible redress

In 1915, the first phase of the stabilising actions was to increase the authority’s understanding of the protest movement and of the situation. Meanwhile, the authorities took immediate measures to show they had heard and taken seriously the protestors. Throughout January 1916, the peaceful and mainly non-violent demonstrations in Phnom Penh and the dual authority (both Cambodian and French as this was a Protectorate) willingness to listen and understand allowed for real communication (i.e. exchange and listening truly to others, not communication campaigns created by advertisers and spin doctors). As a consequence, understanding arose. The only exception took place in Prey Veng. There, the anti-German fears and related belief in a foreign plot of the Resident forbade communication.

The authorities took note of the various reasons for discontent. They gave immediate satisfaction to the protestors on the feasible and most urgent points, such as the buy-back of prestations done by a 22 January 1916 Royal Ordinance. By 1st February, the number of demonstrators reaching Phnom Penh had decreased to a few hundred.

In France, on 10 December 2018, the President announced measures that could partially answer the demands of the people. He also declared the start of a Great National Debate. Yet, the measures hardly actually solve the fundamental purchasing power problem of the French protestors. Meanwhile, nothing addressed their feeling of injustice. Communication seems to have improved, but only marginally. Furthermore, the many disparaging comments of elements of the elite and of the political authorities let the Yellow Vest believe that real communication is not indeed complete. The announce of the Great National Debate, however, may be seen as the promise of a real communication.

As a result, the mobilisation, actually, did not substantially decrease. If we take as benchmark our past example, we should have no more than a dozen people or so still demonstrating in France. It did not continue increasing either. It appears to remain stable.

Furthermore, the opinion surveys stubbornly remain favourable to the movement by more than 50% (see Wikipedia synthesis of results). There is a decrease compared with the start of the movement yet at least half of the country supports the protest. By comparison, only 31% of the French people have a favourable opinion of President Emmanuel Macron (25 January 2019 Survey BVA pour Orange, RTL et La Tribune). Meanwhile,Prime Minister Edouard Philippe reaches 36% (Ibid.). The same survey gives a 64% support to the Yellow Vest Movement (Ibid.). 53% of the French wish the movement to continue.

We are thus neither in a real stabilisation nor in an escalation but in an in-between phase. The movement may go one way or another. However, the Yellow Vest being more supported than the political authorities, the odds seem to be in favour of escalation.

Thus, compared with the Cambodian case, the French situation starts now the second phase at a high level of tension, with a continuing mobilisation.

Stabilisation phase 2: Rebuilding trust and asserting legitimate authority

Communication and Trust

In 1915, the second phase was to increase the feeling of understanding and communication and to build trust to permit in-depth work towards reforms. The permanent commission of the council of ministers under leadership of the Résident Supérieur began to reflect on the peasants’ grievances. The King, after having condemned violence, abuse and the massive protests in Phnom Penh because they favoured unrest, issued a proclamation that detailed all grievances and announced that they would be seriously examined. Thus, by 10 February, the situation in Phnom Penh was judged normal.

Selective and Just use of Force

A reassertion of the authority’s monopoly of violence through selective and just use of force accompanied these two phases. In the provinces, as the authorities had understood the three phases of the protest, it had the possibility to discriminate between different kinds of leaders and to know where and how violence originated. Thus, the state could reassert its monopoly of violence in a selective and proper way. The central authority struggled against any provincial authorities’ unjustified use of violence. They fought against excessive and unfair punishment (all intrinsically escalating) and penalised them when they happened.

Thus, the means of violence remained in the hands of the authorities. This prevented the perception of a waning authority that would have led to more escalation. For example, towards the end of the movement, the villagers helped the authorities to suppress agitation and arrest agitating leaders.

Fundamental Beliefs

The authorities understood and considered the fundamental beliefs of the population and the specific structure of religious institutions and practices. Yet, they also avoided escalating ways. Indeed, they prevented people to take advantage of the latter. In agreement with the heads of the two Buddhist branches (Mohanikay and Thommayut), they suspended all travels by monks to Siam. They informed all pagodas of this measure to prevent rebellious leaders using Buddhist robes and Pagodas networks to escape.

In the meantime, from the second part of February 1916 onwards, the King and the ministers, representing respectively the symbolic and acting parts of the Kampuchean authority, toured the most agitated provinces, explaining the proclamation, and the reforms on the one hand, scolding villagers for their behaviour, on the other. These tours first reinforced the feeling of communication and understanding. Second, they lent legitimacy to the authorities’ actions and declaration of future actions. Third, they contributed to ensure that potentially remaining demonstrators would not travel to Phnom Penh. Thus, they would not drag along other villagers. In turn, this decreased opportunities for violence. Residents similarly toured the less agitated provinces.

By the end of February 1916, the movement had ended.

French Measures

The Great National Debate

Compared with the French Yellow Vest Protest, we see the crucial importance of the Great National Debate. Indeed, it is an absolute necessity to truly create communication, to rebuild trust and legitimacy and to find solutions.

Meanwhile, the political authorities must also go and see the people. This is what seems to start happening, for example with the President organising large meetings with mayors. However, some signals would indicate that we are also facing an orchestrated communication campaign – not to confuse with understanding and communicating (e.g. Gerard Poujade (French mayor) “Souillac Inside“, Le Blog de Mediapart, 20 janvier 2019).

Thus, to know if the political authorities will succeed in stabilising the French Yellow Vest Movement, monitoring the way the Great Debate takes place is crucial. It must not be about convincing people that this or that policy is right and will bear some fruits in an unknown time. It has to be about listening to all fundamental grievances and feeling of injustice and finding ways to address them.

Fundamental Beliefs

Historically constructed beliefs and norms, including fundamental respect for others, as constructed in France will also need to be respected. The resurgence of the use of old regional flags as well as the use of the Marseillaise, the French national hymn, by the protestors, are an indication that these deep collective beliefs are operating.

Just use of force?

Finally, the means of violence definitely remain in the hand of the political authorities, but is their use perceived as just and legitimate, considering the fact that the other stabilising elements tend, so far, not to be fully present?

The loss of an eye by a protestor on 26 January, as well as the number of casualties among demonstrators that the media initially ignored, and the political authorities rarely acknowledged may indicate that the conditions for a perception of a just use of force are not present. An indication of this phenomenon is the absence of precise and updated figures regarding casualties. On 20 December 2018, the official number of casualties was 1843 for the Yellow Vest and the college students (which briefly protested) and 1048 for the police force (“Gilets jaunes et lycéens: 2891 blessés depuis le début du mouvement“, BFMTV, 20 December 2018). At the end of January, we only have mid-January blurred official figures of 2000 Yellow Vest and 1000 policemen (AFP, “Gilets jaunes” gravement blessés: la colère monte et met la police sous pression“, Le Point, 17 January 2019)

Furthermore, the police force (including the Gendarmes) also increasingly expresses grievances, similar to those of the Yellow Vest (e.g. Syndicat Alternative “Gilets jaunes, ras-le-bol policier, revendications” 15 Dec 2018; “Nous aussi on va les enfiler, les gilets”, prévient un syndicat de police“, Valeurs Actuelles, 10 Dec 2018; “IJAT des gendarmes mobiles : toujours pas payée …“, APNM GendXXI,25 January 2019)

In 1915, symbolic and coercive power interacted, mutually reinforced each other and lent legitimacy to the authority-system. Now, in France, the dynamics does not look as positive.

Stabilisation phase 3: in-depth reforms

In Cambodia in 1915, the third phase, in-depth reforms, could now begin, as promises had been made with the King’s proclamation and had to be held. The Résident Supérieur took immediate measures aimed at reducing abusive or erroneous practices in tax collection, prestations and requisitions. For example, he recommended that Residents get closer to the population by multiplying tours to ensure effective control of the lower levels of the Kampuchean administrative apparatus. Posters were put up in all villages to explain to the inhabitants which taxes were owed by whom. Meanwhile, the dual authority had to examine the validity of the other complaints and to propose reforms, that were studied, discussed, enacted and applied by the end of 1917.

Thus, we can see first that communication was necessary to permit stabilising actions. The pooling of resources at all levels of the politico-administrative apparatus in a bottom-up and horizontal fashion was also crucial. The authority worked in a dual fashion. If final decision-making power remained vested in the French, it still reflected joint work. Indeed, the Resident did not discard the suggestions of the Cambodian Assembly. He incorporated most of them into the final decisions.

Second, the speed with which the political authorities acted was stabilising. The visibility of the first phase of actions, compensating for those that had to be delayed, strongly contributed to the stabilisation.

Finally, the Cambodian case confirms the necessity of multi-dimensional actions truly addressing the grievances of the protestors, selective and fair use of force and the importance of sustained and persistent efforts. The dual authority had taken the measure of the discontent and consequent risks, persisted in its stabilising efforts, and thus stabilised the situation for the next twenty years.

France and the Future

To assess what will take place in France, we shall thus need to monitor what happens with the results of the Great Debate. Furthermore, and notably, the fundamental demands of the people will have to be addressed and solved.

Two batches of measures and policies will be necessary. Some will have to be short-term and truly solve purchasing power issues and injustice feelings. They will need to allow for the longer term measures to become operative. Sole operations of “false communication” or “pedagogy” will not work, if the situation is to be properly stabilised. The real implementation of the shorter term measures will be all the more important that the protest has not been stabilised in stage 1 and remains at a high level of tension in stage 2.

Alternatively, the French political authorities may choose to use coercion and force. Indeed, one must never underestimate the power of violence of the state. Yet, this is a more expensive and less efficient way to govern. Internationally, in term of national wealth and competitiveness, and thus, ultimately, power of the ruling elite and political authorities, this would probably be a sub-optimal strategy. We may also wonder, considering the grievances of the police force if such a policy is feasible at all.

Last but not least, we may wonder if the French political authorities and France indeed can stabilise the movement. In other terms, can the country address all the grievances of the population and its feeling of injustice considering the international situation, the profound changes resulting from new technologies and climate change. Indeed, we are probably in an overall escalating phase, because the various institutions built in the past are not anymore fully adequate to deal with the reality of a transformed present, of a paradigm shift, and of the multiple pressures that we must face. To be able to reach stability again, we must adapt, transform, sometimes create, everything, from capacities to understand and beliefs, if we want to properly handle changes and be ready for the future.

In this framework, protest movements are a constructive and crucial component of ours societies’ evolutions. It is only through the interactions they prompt, through the change they impose that a new better adapted system may hope to emerge.

This is what the Yellow Vest movement may bring to France, if the actors transmute the movement in a new national momentum, adapted to the 21st century. The other possible scenarios range from revolution and civil war, to apathy, loss of national wealth and capabilities to handle change and threat.

About the author: Dr Helene Lavoix, PhD Lond (International Relations), is the Director of The Red (Team) Analysis Society. She is specialised in strategic foresight and warning for national and international security issues. Her current focus is on Artificial Intelligence and Security.

References and Bibliography

To find, check and follow events, dates and facts on the Yellow Vest: for example, The Guardian “as it happened“; Le Figaro; France Info, Mediapart, etc.

For the Cambodian case, the references are in the first part of the article.

Kant, Immanuel, Political Writings edited by Hans Reiss, (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1991).

Doyle, Michael W. 1983. “Kant, Liberal Legacies and Foreign Affairs,” Part 1 and 2, Philosophy and Public Affairs, vol. 12, nos. 3-4 (Summer and Fall).

Scott, James, Weapons of the Weak: Everyday Forms of Peasant Resistance. Yale University Press, 1985.