As the noose seems to be slowly tightening around the Islamic State in Mesopotamia, it is even more important to consider the global dimension of the Khilafah. It is indeed likely that all geographical components will be used by the Islamic State in its will to counter-attack and survive.

A strong indication confirming the global character of the war waged by the Islamic State and its Khilafah came through al-Baghdadi’s 26 December 2015 audio message, “And wait, for we are also waiting ” (Pietervanostaeyen), where the place of Somalia we highlighted previously (see “Facing a Strategic Trap in Somalia?), as well as importance of Bangladesh, Indonesia and the Philippines, as we shall focus upon now, were confirmed.

“O Muslims, indeed engaging oneself in this war is obligatory on every Muslim, and no one is excused concerning it. And indeed, we call on you altogether in every place to mobilize, and we specify the sons of the lands of al-Haramayn (the two sanctuaries). So march forth, whether light or heavy, old or young. Rise, O grandsons of the Muhājirīn and Ansār (companions of the Prophet Muhammad). Rise against Āl Salūl (the House of Saud), the apostate tawāghīt (tyrannical rulers), and support your people and your brothers in Shām, Iraq, Yemen, Afghanistan, the Caucasus, Egypt, Libya, Somalia, the Philippines, Africa, Indonesia, Turkistan, Bangladesh, and in every place.”

This article ends the part of our series singling out risks to a strategy that would only or mainly pay attention to one theatre of war and to one dimension and focusing on the Islamic State global geographical implantation. It looks at three maybe less known cases of global outreach for the Islamic State and its Khilafah: Malaysia and Indonesia, as well as the Philippines in SouthEast Asia and Bangladesh in South Asia.

The Islamic State in Southeast Asia

The Islamic State in Indonesia and Malaysia

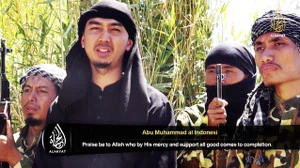

Indonesia and Malaysia are an example of the first type of “ribat“* we singled out previously, i.e. when al-Baghdadi has accepted the allegiance (bay’a) pledged by groups. Indeed, as analysed by V. Arianti and Jasminder Singh (“ISIS’ Southeast Asia Unit: Raising the Security Threat“, RSIS Commentary, 20 Oct 2015), more than 20 groups have pledged bay’a and seen it accepted by Al Baghdadi in November 2014. Since then, they have united under the Jamaah Ansharut Daulat (JAD) in March 2015. Meanwhile, in Mesopotamia, one finds a “corresponding” fighting unit, the Katibah Nusantara (KN or or Majmuah Al Arkhabiliy in Arabic). According to Arinati and Singh, “KN  continues to expand geographically within a year of its establishment” “in Shaddadi, Hasakah in Syria in September 2014”. “There are about 450 Indonesians and Malaysians, including children and women under fealty to ISIS in Iraq and Syria today”. “It has since the middle of this year, divided into three geographical groupings: KN Central led by Bahrum Syah; Katibah Masyariq led by Salim Mubarok At-Tamimi alias Abu Jandal, based in Homs and Katibah Aleppo led by Abu Abdillah. Bahrum Syah remains amir of KN, dealing strictly with Indonesian ISIS fighters that defy or defect from KN’s instructions, to maintain unity within ISIS.”

continues to expand geographically within a year of its establishment” “in Shaddadi, Hasakah in Syria in September 2014”. “There are about 450 Indonesians and Malaysians, including children and women under fealty to ISIS in Iraq and Syria today”. “It has since the middle of this year, divided into three geographical groupings: KN Central led by Bahrum Syah; Katibah Masyariq led by Salim Mubarok At-Tamimi alias Abu Jandal, based in Homs and Katibah Aleppo led by Abu Abdillah. Bahrum Syah remains amir of KN, dealing strictly with Indonesian ISIS fighters that defy or defect from KN’s instructions, to maintain unity within ISIS.”

If the Malaysian-Indonesian group’s involvement had been mainly focused, as pointed out by Aranti and Singh (ibid.) on hijrah, i.e. migration to the land of the existing wilayats, the threat of the Islamic State was serious  enough to have been specifically noted and singled out in the 16 March 2015 Joint Declaration of the ASEAN Defence Ministers on Maintaining Regional Security and Stability for and by the People (p.4) and identified as top threat by Singaporean Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong in his keynote address at the IISS Shangri-La Dialogue on 29 May 2015 (see also Ibrahim Almuttaqi “The ‘Islamic State’ and the rise of violent extremism in Southeast Asia“, Habibie Center, July 2015).

enough to have been specifically noted and singled out in the 16 March 2015 Joint Declaration of the ASEAN Defence Ministers on Maintaining Regional Security and Stability for and by the People (p.4) and identified as top threat by Singaporean Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong in his keynote address at the IISS Shangri-La Dialogue on 29 May 2015 (see also Ibrahim Almuttaqi “The ‘Islamic State’ and the rise of violent extremism in Southeast Asia“, Habibie Center, July 2015).

We also need to point out a potentially important role played by the Indonesian groups in spreading the Islamic State psyops and message, as so many of the latter seem to be published through websites and “usernames” with a Bahasa Indonesia (Indonesian) component. A systematic study would be necessary to determine the extent of the involvement.

Renewed and lethal activity for groups following the Islamic State in the Philippines

In the Philippines, groups such as Abu Sayyaf, Jamā’at Anṣār al-Khilāfah (video on Jihadology.net), or Bangsamoro Islamic Freedom Fighters (BIFF – see Stanford Group Summary) started pledging bay’a to al-Baghdadi over the Summer 2014 (for a complete list, see “Islamic State’s 43 Global Affiliates Interactive World Map”, IntelCenter; “Red alert in Sabah over Abu Sayyaf-IS links”, 22 Sept 2014; Michelle Florcruz “Philippine Terror Group Abu Sayyaf May Be Using ISIS Link For Own Agenda”, 25 Sept 2014).

Until al-Baghdadi’s 26 December 2015 speech, it was unclear if these pledges had been fully accepted or not, including because the videos, if they look like official Islamic State’s ones, nevertheless emanate from indigenous groups and thus represent these groups and not the Khilafah, as long as endorsement has not been given. Such ambiguity regarding the Philippines has now disappeared, in a very general way, and we may thus update accordingly our map, to which we shall also add the U.K (see below).

More recently, a new pledge was published on 4 January 2016 by the “Mujāhidīn in the Philippines” (video on Jihadology.net). Meanwhile another video showing an Islamic State’s training camp in the Philippines surfaced on 20 December 2015 (“Jund al-Khilāfah in the Philippines: “Training Camp” Jihadology.net). Interestingly, by trying to continuously deny the Islamic State’s presence on its territory, the Philippines’ State administration finally confirmed the existing linkages between the Islamic State and local groups – which is absolutely not surprising as it is the way the Islamic State spreads – when Communications Secretary declared, to try minimising the training  camp existence: “What ISIS-linked personalities have done is to try to link-up with local jihadist/terrorist groups… Some of these ISIS-linked personalities, who are really few in number, have also sought refuge in the base areas of these local terrorist groups” (Patricia Lourdes Viray, “No ISIS training camps in the Philippines“, 22 dec 2015 & Aurea Calica, “No credible ISIS threat in Philippines“, 29 Nov 2015, The Philippine Star).

camp existence: “What ISIS-linked personalities have done is to try to link-up with local jihadist/terrorist groups… Some of these ISIS-linked personalities, who are really few in number, have also sought refuge in the base areas of these local terrorist groups” (Patricia Lourdes Viray, “No ISIS training camps in the Philippines“, 22 dec 2015 & Aurea Calica, “No credible ISIS threat in Philippines“, 29 Nov 2015, The Philippine Star).

Then, over Christmas, 200 fighters, involving notably BIFF carried out “at least eight attacks” in three provinces against Christian villages and military outposts, killing 14 villagers, while the military killed 5 rebels, according to regional military spokeswoman (Jim Gomez, The Associated Press, “14 dead as Islamic rebels attack in Philippines“, USAToday, 26 Dec 2015).

We may wonder if the next Dabiq will not emphasise the Philippines and Southeast Asia, as the Khilafah may well be keen to include any group “serious enough” and action to demonstrate its staying power, assuming potential tensions with JAD and KN have been solved.

Towards a coordinated Islamic State umbrella group for Southeast Asia?

With a relatively strong presence in the three countries, when the Mesopotamian wilayats of the Islamic State are under strong attack, it is likely that efforts will be made to at least coordinate Islamic State’s endeavour in Southeast Asia. The aim could be to see a group emerge which is strong enough to allow for the creation of a wilayat, as a variation on the model used for the Sinai (A ymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi, “The Islamic State and its ‘Sinai Province’“, Tel Aviv Notes: Moshe Dayan Center, 26 march 2015). Indeed, globally, stronger and more successful actions in Mesopotamia, or in Mesopotamia and Libya, in the war against the Islamic State, to take the two most likely intense theatres of war in the near future, are likely to see attempts by the Islamic State to loosen the grip by opening new fronts, besides also disorganising the enemy with new attacks. Here the creation of a wilayat over Indonesia, Malaysia and the Philippines, or part of them, would also reflect the Islamic State’s will to destroy borders considered as imposed by what is perceived by the Islamic State as “idolatry and nationalism” (video “And No Respite”, Al Hayat media Foundation, 24 Nov 2015, Jihadology.net). Should such a wilayat be declared in Southeast Asia, its strength and evolution would have to be carefully monitored, as suggested previously (see Understanding the Islamic State’s System – Structure and Wilayat, 4 May 2015).

ymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi, “The Islamic State and its ‘Sinai Province’“, Tel Aviv Notes: Moshe Dayan Center, 26 march 2015). Indeed, globally, stronger and more successful actions in Mesopotamia, or in Mesopotamia and Libya, in the war against the Islamic State, to take the two most likely intense theatres of war in the near future, are likely to see attempts by the Islamic State to loosen the grip by opening new fronts, besides also disorganising the enemy with new attacks. Here the creation of a wilayat over Indonesia, Malaysia and the Philippines, or part of them, would also reflect the Islamic State’s will to destroy borders considered as imposed by what is perceived by the Islamic State as “idolatry and nationalism” (video “And No Respite”, Al Hayat media Foundation, 24 Nov 2015, Jihadology.net). Should such a wilayat be declared in Southeast Asia, its strength and evolution would have to be carefully monitored, as suggested previously (see Understanding the Islamic State’s System – Structure and Wilayat, 4 May 2015).

So far, we have indications showing that efforts at coordination are underway. Anṣār al-Khilāfah would reportedly be trying to coordinate with Indonesians (Jerry Adlaw, “ISIS exists in Mindanao“, The Manila Times, 5 Jan 2016). A previous report from Malaysia also tends to indicate similar ongoing efforts, this time by a Malaysian, ex university lecturer, Dr Mahmud, with Abu Sayyaf, to unite all groups having pledge ba’ya to al Baghdadi in a single Southeast Asian umbrella (Farik Zolkepli, “Regional ISIS faction to unite Malaysia, Indonesia and Philippines terror cells“, AsiaOne, 14 Nov 2015).

Meanwhile, actions on and from this particular ribat* – be it or not declared as wilayat – could be intensified.

Such a successful unification or, more likely, coordination of groups having pledged allegiance to al-Baghdadi, to say nothing of the declaration of a wilayat, would further raise the level of threat to the region, including if it involved fighters returning from the Mesopotamian battlefield, tasked with spreading the Khilafah, as underlined by Singapore’s Defence Minister in remarks during a trip to the U.S. in December 2015: “The danger is the link up and formalization [of ties] between these groups” (Prashanth Parameswaran, “Singapore Warns of Islamic State Terror Nexus in Southeast Asia“, The Diplomat, 10 Dec 2015).

Renewed lethal and competing state-like actions from Indonesia, Malaysia and the Philippines, could couple and link, in the region, with actions of a more “individual” nature (as in Bangladesh, see below) on enemy targets, as the Russian FSB fears in Thailand and about which they warned Thai authorities (e.g. Bangkok Post, 4 Dec 2015). Here, we may see how the refusal by the Islamic State to accept the modern state order, grounded on territoriality, sovereignty and independence (see H Lavoix, “Monitoring the War against the Islamic State or against a Terrorist Group?“, 29 September 2014.; “The Islamic State Psyops – Worlds War“, 19 January 2015; “The Islamic State’s Psyops – Ultimate War“, 9 February 2015) and the will to create another system mixed with the internationalisation or globalisation of national interests and influence challenge the modern order. National threats cannot anymore be seen as targeting only the national territory stricto sensu – assuming it has ever been possible to perceive them as such and we are not here victim of an illusion prompted by norms. In response, state’s administrations must work closer and better together, including in terms of intelligence and security which is, notably for intelligence services used to share only parsimoniously and reluctantly intelligence, a huge challenge.

Islamic State’s new actions could also link up with the current Rohingya (a Muslim community in Myanmar) crisis and fragility, involving refugees, migrants, and feelings of injustice on a backdrop of religious tension (e.g. Eleanor Albert, “The Rohingya Migrant Crisis“, CFR Backgrounder, 17 June 2015; Alistair Cook, “Human Insecurity and Displacement along Myanmar’s border” in Jiyoung Song, Alistair D. B. Cook, ed. Irregular Migration and Human Security in East Asia, 2015), as is clear from the case of Bangladesh to which we shall now turn.

Bangladesh

Bangladesh is a recent example of the third “ribat”* category, we singled out previously, i.e. when attacks have taken place and been claimed, sometimes as extensions of the operations of non-Mesopotamian wilayats. In Bangladesh six attacks have been carried out successfully and claimed by the Islamic State, despite denial by authorities of any Islamic cell in their country and accusations against local Islamist groups (e.g. BBC News, 27 Nov 2015). Three attacks singled out any foreigners, who were shot by individual assailants on motorbikes: an Italian on 28 September 2015, a Japanese on 3 October and again an Italian, this time a missionary, on 18 November 2015 (e.g. Annie Gowen, “For foreigners, fears grow over killings claimed by Islamic State in Bangladesh“, The Washington Post, 20 Nov 2015). Two other attacks targeted Shi’a Muslims: on 24 October 2015 (BBC News), during the Ashura celebrations, a grenade attack was carried out against a Mosque in Dhaka, killing one person and injuring 80; on 26 November 2015 (BBC News) another attack was perpetrated against again a Shi’a Mosque in the north-west of the country, killing one and wounding at least 3 people. Finally on 26 December 2016, a ‘suicide bomb’ attack at Ahmadiya mosque in Chakpara village (Bagmara Upazila, Rajshahi District) killed one person and wounded 10 and was claimed by the Islamic State (DhakaTribune, 26 & 27 Dec 2016).

As analysed by Animesh Roul, early indications of potential developing links between the Islamic State and Bangladesh were identified in June 2014, (psyops video “No Life without Jihad”), then through the arrest of a recruiter in September 2014, recruitment having started in early 2014 (Animesh Roul, “Spreading Tentacles: The Islamic State in Bangladesh“, Terrorism Monitor 13: 3, February 6, 2015).

Now, the status of Bangladesh as ribat* for the Islamic State has been confirmed first by a nasheed (a capella song) “Applaud the return of the Khilafah in Bengal” (Al Hayat Media Center, 27 October 2015), then by Dabiq #12 (Al-Hayat Media Center, 18 Nov 2015) with the article “The revival of jihād in Bengal with the spread of the light of the Khilafah”, pp. 37-41. There, the Islamic State reasserted the unique legitimacy of the Khilafah against other “independent groups”, i.e. having not pledged allegiance to al-Baghdadi, such as “‘Jamā’atul Mujāhidīn,’ ‘Al-Qā’idah,’ or any other group,” and stressed that the awareness of the Khilafah’s existence led to the unification of “true” Bengali Jihadis (pp. 39-40). Always according to Dabiq, the attacks mentioned above, as well as one on a police station, were carried out by “soldiers of the Khilāfah in Bengal [who had] pledged their allegiance to the Khalīfah … unified their ranks, nominated a regional leader, gathered behind him” (p.41).. and who “become a source of strength and support for the oppressed Muslims in both Bengal and Burma” (ibid.).

The case of Bangladesh emphasises four elements. First, and this is particularly important in terms of warning and thus in terms of prevention, it underlines once more the variety of modus operandi used by the Islamic State, including the call to individuals to act without necessarily first establishing a complex cells or underground network of die-hard terrorists, as was shown, for example, in the case of the 9 January 2015 attacks by Coulibaly in France (e.g. BBC News, 13 Oct 2015), and again, always in France, by the attack against military personnel in Valence on 1 January 2016 (despite denial by the prosecutor sticking to an outdated understanding of the Islamic State and of “terrorism”) and probably in the case of the attack on a police station in Paris on 7 January 2016 (Europe 1, 2 January 2016; Angelique Chrisafis, The Guardian, 8 January 2016). This modus operandi was again reminded in Dabiq #12 in the reference to Islamic State’s spokesman Al-Adnani (p.40). A few contacts, a light network of like-minded people, or just individual belief in the Islamic State and its Khilafah may be enough to generate action.

Furthermore, Islamic States’ partisans also favour operations that are relatively easy to organise, yet deadly and complex to stop, as pointed out by Watts in his paragraph “Al Qaeda Tried Too Hard — ISIL Gets It” (Clint Watts, “What Paris taught us about the Islamic State”, War on the Rocks, 16 Nov 2015). Meanwhile, the Islamic State can use its psyops products for any kind of practical “fighting” advice to far away untrained “fighters”, as shown by the article “Et préparez contre eux tout ce que vous pouvez comme force” (Dar al-Islam #6, 27 Sept 2015: 34-39). There, it minutely explained how to handle and use various weapons.

In those cases, we may wonder if the Islamic State’s psyops products, including in terms of content, have not become one of the best place where to find indications that something is going to happen, where and how, besides successful attacks themselves, which trigger new ones. True enough, the information thus gathered may not have the degree of precision or the nature of those usually sought in counter-terrorism, but they should nevertheless be considered as helping narrowing down the field of possibilities. Combined with more classical counter-terrorist intelligence surveillance and psyops’ analysis, as inherited from previous periods including the fight against Al Qaeda until the birth of the Khilafah, it could help towards a better warning regarding potential future attacks and thus towards prevention.

The case of Bangladesh also stresses again a new type of threats to the societies attacked, where anyone, anywhere, can be the target of pretty much anyone who decides to answer the call of the Islamic State, as we already pointed out (“Worlds War” and “Ultimate War“) and as was also most probably operative in the San Bernardino and London tube attacks (BBC News, “Leytonstone Tube station stabbing a ‘terrorist incident’“, 6 Dec 2016; “2015 San Bernardino attack“, Wikipedia).

Second, the attacks in Bangladesh confirm once more the anti-Shi’a component of the Islamic State’s beliefs and aims (see all issues of Dabiq). The Islamic State does not only attack Shiites as enemies but, by so doing, also favours a heightening of a competition within the Sunni world for sectarian legitimacy. In this sectarian race, the harsher against Shiites, the more legitimate in term of Sunni Islam. This aspect has fundamental consequences in terms of creating a working coalition to fight the Islamic State, as it favours a division among the Khilafah’s foes, when those are not wise enough to overcome the lure of sectarianism mixed with other ambitions, as we witness for example in the case of Saudi Arabia, where its regional ambitions, multiple tensions resulting from a competition related to oil and the war in Yemen, seem to have priority over the war against the Islamic State (e.g. DeutscheWelle, “German spy agency warns of Saudi intervention destabilizing Arab world“, 2 Dec 2015; Fatima Ayub, ed. The Gulf and Sectarianism, European Council on Foreign Relations, 91, Nov 2013), as probably again indicated by the heightening of tensions with Iran following the execution of Shi’a Sheikh Nimr al-Nimr (e.g. Paul Iddon, “Was Saudi Arabia’s execution of Sheikh Nimr calculated or reckless?“, Rudaw, 8 Jan 2016; Jon Schwarz, “One Map That Explains the Dangerous Saudi-Iranian Conflict“, The Intercept, 6 Jan 2016)

Third, exemplifying our related general comments in “A Global Theatre of War“, the attacks have an impact on Bangladesh resources, including intangible ones. The police needs to use resources to investigate attacks, the medical institutions must treat the wounded, while life is lost. Then, the fear created by the heavy use of terrorism, added to the incapacity of states and their governments to prevent them, has a direct economic impact: in the case of Bangladesh, multinationals and other contractors reduced their travels to the country which may seriously hamper the garment business (Ruma Paul, “Western retail giants restrict travel to Bangladesh after attacks“, Reuters, 14 Oct 0215). Finally, incapacity to face the threat added to Bangladesh authorities’ denial has the potential to damage the legitimacy of the political authorities. It could thus contribute to an already existing fragility of the state, as underlined by C. Christine Fair (“Islamist Militancy in Bangladesh: Then & Now“, Jihadology Podcast, 11 Nov 2015), or by Michael Kugelman and Atif Jalal Ahmadto (“Will ISIS Infect Bangladesh?“, The National Interest, 8 Dec 2015). In turn, if fragility rises, then it will probably become easier for the Islamic State to spread and entrench itself.

Finally, being able to operate through successful attacks in a far away non-Arab country – and this is of course also valid in the case of Southeast Asia – enhances the status that the Islamic State and its Khilafah want to project: that they are for truly all Muslims and are freely joined for this reason (see part Salafism as answer in H. Lavoix, “The Islamic State Psyops – Foreign Fighters’ Complexes (2)“, RTAS, 30 March 2015). Indeed Dabiq‘s article on Bangladesh (ibid.) stresses the self-made indigenous character of the group, with an indigenous leadership, which joined the Khilafah. Reciprocally, the alleged emergence of this self-made group enhances the Islamic State’s charisma as it is, always according to Dabiq, because of the creation of the Khilafah that fighters in Bangladesh found the strength to unit and to carry out their jihad. As previously in the case of the Southeast Asia, but here in a way that is explicitly spelled out in Dabiq, we see an early indication of a potential linkage with the Rohingya crisis.

These cases of global geographical implantation of the Islamic State and its Khilafah emphasise the linkages existing between various theatres of war and how crucial it is to include this global dimension in any strategy to fight the Islamic State.

Note —

* Ribat: the a-geographical potentially shifting “borders” of the Khilafah, or where it is carrying the fight, in various, more or less intense ways as seen when studying its worldview in “Worlds War” and “Ultimate War“, building notably on Magnus Ranstorp‘s explanation: ribatmeans “placing oneself at the frontlines where Islam was [is] under siege” (Statement 31 December 2003, using Bin-laden’s mentor Azzam book Caravan of Martyrs).

Featured image: Still from the video “Training Camp” by Jund al-Khilāfah in the Philippines – 30 Dec 2015.

About the author: Helene Lavoix, PhD Lond (International Relations), is the Director of The Red (Team) Analysis Society. She is specialised in strategic foresight and warning for national and international security issues.