Farmers’ protests have spread throughout Europe (notably France, Germany, Hungary, the Netherlands, Poland, Romania…) since at least mid-2023 with escalation at the start of 2024, as well as in India although for different reasons. In this light, we republish two articles that address the issue of protests and how they should or could be answered.

This article constitutes the first part and explains how and why protest movements spread, through which dynamics. The second article focuses on the role of governments and political authorities in stabilising or escalating movements. It locates protests movements in a larger more encompassing dynamic that is at work since at least 2010.

France faced an escalating protest movement in 2018-2019. This movement was called the “Yellow Vests” or “Yellow Vest”. The French government appeared to be always late in the way it answered it; political analysts appeared to be surprised by what was happening and to struggle to understand. Meanwhile, violence increased.

Part 2 of the article: Stabilising Or Escalating a Protest Movement?

Here we explain how a protest movement starts with a triggering demand, then spreads and grows in terms of scope and intensity, pointing out similarities with the French situation.* In the winter 2018-2019 French case, the rising loss of legitimacy not only of the government, but also of the state, dramatizes the situation and makes the matter worse.

As soon as 2011 we foresaw the rise of new political opposition movements. Indeed, geo-temporal spread must also be understood across countries, all the more so in the age of the world-wide-web and of connected societies and groups.

Since December 2010 with the “Arab Spring,” protests and demonstrations have so much flared successively in so many countries that all should be aware, at least, that something is going on.Among others, this allowed for the feared rise of “populism”, we explained in other articles. Furthermore, earlier (weak?) signals could be found with the French 2005 riots and 2006 students’ protests, with the 2007-2008 food riots, as well as with violence in Greece during the winter 2008-2009. In 2007-2008, fifteen countries, mainly in Asia and Africa were hit by the food riots. Since then at least 25 countries (Bahrain, Belgium, Canada, Egypt, France, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Iraq, Jordan, Libya, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Russia, Spain, Syria, Tunisia, Thailand, Ukraine, Turkey, the U.S., UK, Yemen) have been the theatres of various types of protests with different kinds of escalations up to civil war, while sporadic demonstrations also occurred elsewhere in the MENA countries, with the Arab Spring, in Latin America and Asia, following the Spanish Indignados and then Occupy movements back in the years 2011-2012.

The recurrence and spread of those movements, their links (either direct – notably since the Arab Spring, people on social networks know and help each other – or in the world of ideas, as people have learned from other movements they witnessed), even if each mobilisation has its own dynamics and challenges, show that, in general, stabilisation is not at work. Could a case from the past help shed some light on what is happening or not happening?

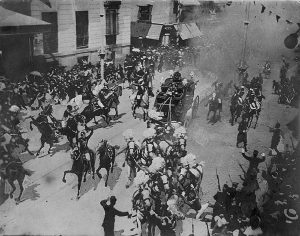

The 1915-1916 peasant movement in Cambodia involved up to 100.000 people, which represented approximately 5% of the population of the country, 30.000 of whom reached Phnom Penh (i.e 1,8%) to demonstrate peacefully.[1] To give a better idea of what such mobilization represents, nowadays, for a country like the U.K. or France, 5% demonstrators would imply approximately 3 million people; for the US, 15 million people. In France, according to Government’s figure which are believed to be vastly underestimated, the Yellow Vest were 283.000 on 17 November 2018 (a Union of policemen gives more than a million people), 106.000 on 24 November and 75.000 on 1st December (i.e. respectively out of 67.12 million inhabitants, World Bank, 0,4%; 0,15% and 0,11%). as comparison, in 2012, in Tunisia, on 19 and 20 February, 40,000 protesters were in the streets, and on 25 February, 100.000, i.e. respectively 0,37% and 0,9% of the estimated 2012 population.

The French global figures for 17 November 2018, however, hide a different reality if we look at local figures, as shown by the map below as reconstructed from the original map made by demographer Hervé Le Bras (see original article and map here)

by MrAlex19 [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], via Wikimedia Commons copied from 17 November Map by Demographer Hervé le Bras – Click on map to access the original map on France 3.

The peasant movement in Cambodia, thus, representing 5% of the population, was thus huge quantitatively.

Causes, build up and lack of awareness

The main causes for the Cambodian peasant protest were reinforcing inequalities, when these were not perceived as such and thus not tackled by the political authorities (the dual administration of the French Protectorate and of the Kampuchean Kingdom).[2] Peasant resentment had progressively built up around issues ranging from taxes on tobacco to requisitions, with the latter and the underlying prestation or paid corvée system epitomising unfairness. We have exactly the same situation in France, as the Yellow Vests denounce rising inequalities over the last 30 years, and notably since the 2007-2008 financial crisis (e.g. various interviews on French TV, BBC News), as well as, in the French case, a despise shown by the French government and notably the French President Macron against people (e.g. Bloomberg 2 Dec 2018).

Actually, in the Cambodian case, weak signals of discontent had previously existed, witness the multiplying peasants’ petitions brought to governors or residents from 1907 to 1913. Yet, as these signals were spread over time and space, they were insufficient to bring the awareness that would have allowed for reforms. Since the turn of the millennium, France has known a similar situation with a multiplication of unsuccessful protests over the years.

Thus, when the Cambodian peasant movement started and spread, the authorities perceived it as sudden and massive, because of their lack of awareness. Early explanations for the causes of the protest included references to an uprising synchronous with event happening in Cochinchina and the possibility of a German-sponsored plot, maybe involving exiled Prince Yukanthor, his wife and Phya Kathatorn. With hindsight, such a plot, as all conspiracy theory, was far-fetched. Yet, for some of the actors (e.g. the Prey Veng Resident, The Gouverneur Général Roume and his Director of Indigenous Political affairs), it was a reality when the demonstrations exploded.

The insecurity and fear created by World War I, combined with the general European apprehensions regarding anarchist and revolutionary terrorist attacks and assassinations, added to a wariness arising from the removal of most troops from Indochina were conducive to belief in plots. A false understanding and awareness settled that favoured escalation. Indeed, as the protests were not understood, then wrong actions were taken, because those answers were built on the erroneous analysis.

Full awareness and conscious analysis of the widespread and deep peasant discontent reached the highest levels of the dual authority only after the escalation took place, during the Summer 1916.

Trigger

When the Kompong Cham Resident sent convocations for prestation labour to Ksach-Kandal in November 1915 in prevision of road works, even though the peasants had already done their prestation for the year, the villagers used the traditional form of protest to express their discontent. They went to the King to ask for redress. As these specific demands were met, they went back to their villages, but, considering their other motives of discontent, the matter was not closed as the authorities expected.

On the contrary, the villagers planned to come back for more, i.e. the possibility to buy back the 1916 prestations. This was legally offered to them, but rarely used because the small Kampuchean population meant a lack of manpower and thus led to transform prestations into requisitions to see public work done.

In France, the trigger was supplementary taxes on oil, and as in our past case, the other motives of discontent, added to timing discrepancies in the response given by political authorities, forbids the movement to stop, even though the French government finally accepted to postpone the tax (e.g. BBC News). Furthermore, in the French case, postponement rather than cancellation added to the rising distrust between the people on the one hand, the government and the state on the other.

Mobilizing through social network and communication

The villagers spread the words of their earlier protests’ success to neighbouring villages, demanding others to follow the movement. Messages were transmitted orally by travelling leaders and via letters originally sent by the inhabitants of Kompong Cham. The letters’ contents show not only the easy use of threat and the commonality of violence, but also the way the letters were circularised to obtain mobilisation as they were transmitted from villages to villages.

Anonymous letters circulating in the villages of Prey Veng and Svay Rieng (translation 1916) – The inhabitants of Khet Kompong Cham mobilize those of Khet Prey-Veng by using threat:

“The Khum of Lovea-Em has left this letter this 15/1:

“All the village of Kas-Kos must leave on 20/01. If someone does not leave on this date, we shall come in group to hit him with knives without fault. We shall also hit with knives his children and grand-children. Moreover, we shall burn his house – beware to the one who does not leave. Because we are all very discontented.”

Other letters ended with these sentences:

“Once you will have received this letter, seriously take your precautions. If someone does not want to listen; gather and beat him until his last generation.”

Or

“Have this letter circulate in all provinces and khums once you will have read it. Signal any delay in any village and the whole village will be severely punished.

In each Khum, the Mékhum will have to write the words “seen” on the verso.”

Shared discontent, communication and threat allowed the mobilisation to grow and spread.

We need little imagination to see that the processes that are currently at work through Facebook and Twitter are very similar, with “only” different means of communication. Those new media allow for quicker spread, and abolished distances, as pointed out by Bloomberg. As far as the content of current messages are concerned, threats also exist, witness the threats received by the most moderate among the Yellow Vests (e.g. BFMTV).

Space-time pattern: Speed of communication, escalating phases and geographical spread

In the past, the slow means of communication introduced differences in the kinds of mobilisation achieved. Each movement involved three escalating phases:

- Original peasant discontent and consequent demonstrations;

- Young villagers hoping to reach leader status and thus pushing for continuation and spread of the movement;

- Bandits, millenarian leaders or vengeful individuals taking advantage of the created disorders.

Each phase implied escalation in violence. Thus, the further away the villages reached, the closer they would be in terms of time to the more violent phase for the initial villages. Yet, because the authorities, once they started understanding what was happening – even if full awareness had not taken place – were also taking stabilising actions, the further away the villages, the more likely stabilising actions were operative and thus the more likely the initial mobilisation was deflected.

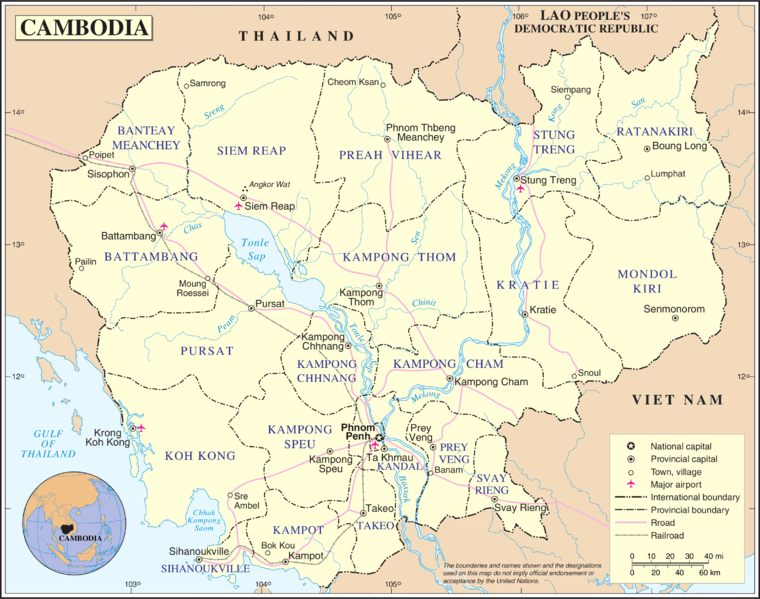

This explains the apparently sudden explosion of violence in some areas, such as Prey Veng, where 2000 demonstrators assaulted the Pearang salakhet (provincial tribunal) to free arrested leaders, and where the Indigenous Guard fired on the crowd killing eight individuals. These areas were far away enough to be reached during the third phase of escalation, but close enough not to feel the effects of stabilising measures. This also explains the quasi or total absence of demonstration in areas located further away, such as Kampot, Takeo, Pursat or Battambang.

The communication speed-rate explains the space-time pattern of the demonstrations. The first demonstrators of Ksach-Kandal reached Phnom Penh on 3 January 1916, the bulk on 7 and 8 January. By 20 January, the inhabitants of various Prey Veng villages had left for Phnom Penh, while the inhabitants of Thbong Khmum in Kompong Cham were about to depart. For Kompong Chhnang, the movement had spread from Choeung Prey to Mukompul in Kompong Cham to Lovek to Anlong Reach in Kompong Chhnang, but could not go further.

The consequences for our present and near future are crucial. Regarding awareness and understanding, thus capability to deal with protests, a slow pace of communication plays into the hands of those who truly want to understand. A slow pace of communication thus favours stabilisation, if we are in an overall stabilising phase.

On the contrary, as is taking place in France, technological sophistication allows speed, collapse of phases, quasi-instantaneous geographical spread, and helps muddling understanding. Besides other biases, this favours de facto escalation in the movement. This escalation in terms of violence is enhanced by the fact that the “cognitive system” of administrative apparatuses does not efficiently incorporate technological changes. Even if, in the case of 2018 France, digital change is integrated, administrative and usual political – or rather politician – processes and practices cannot accommodate the digital instantaneous spread in-built within the movement. The resulting incapacity to understand of the political authorities and elite groups around them forbids awareness, which, in turn, further leads to escalating actions, which, again, contributes to an overall escalating phase.

With the next article, we shall look more in detail at the way political authorities may escalate or, on the contrary, stabilise such a movement.

About the author: Dr Helene Lavoix, PhD Lond (International Relations), is the Director of The Red (Team) Analysis Society. She is specialised in strategic foresight and warning for national and international security issues. Her current focus is on Artificial Intelligence and Security.

*The original title was “Protest Movements, Mobilisation, Geo-Temporal Spread: Some Lessons from History (1)”

[1] This post is a shortened and revised version of pp.114-125, Lavoix, Helene, ‘Nationalism’ and ‘genocide’ : the construction of nation-ness, authority, and opposition – the case of Cambodia (1861-1979) – PhD Thesis – School of Oriental and African Studies (University of London), 2005, where new available evidences allowed to further the analyses by Milton Osborne “Peasant Politics in Cambodia: the 1916 Affair” Modern Asian Studies, 12, 2 (1978), pp.217-243; Forest, Cambodge, pp.412-431. The interested reader will be able to refer to the original text to find detail and full references fo archives. Figures for the mobilization are from A. Pannetier, Notes Cambodgiennes: Au Coeur du Pays Khmer; (Paris: Cedorek, 1983 [1921]); pp.46-47 CAOM/RSC/693/249c/mouv1916IAPI/24/10/1916. Alain Forest estimates the overall population of Cambodia in 1911 at 1,684 million. The 1921 census finds 2,395 million inhabitants.

[2] For a schematic representation, see Lavoix, Ibid, appendix 4.2. p.321, for detailed explanations on the dual authority in Cambodia, see, notably, David P. Chandler, A History of Cambodia, (Boulder: Westview Press, [1992, 2d ed.]); Alain Forest, Le Cambodge et la Colonisation Française: Histoire d’une colonisation sans heurts (1897-1920), (Paris L’Harmattan, 1980); Milton Osborne, The French Presence in Cochinchina and Cambodia: Rule and Response (1859-1905), (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 1969); Lavoix, ibid.