(Art direction and design: Jean-Dominique Lavoix-Carli)

Article updated to include October 2024 and early November 2024 events.

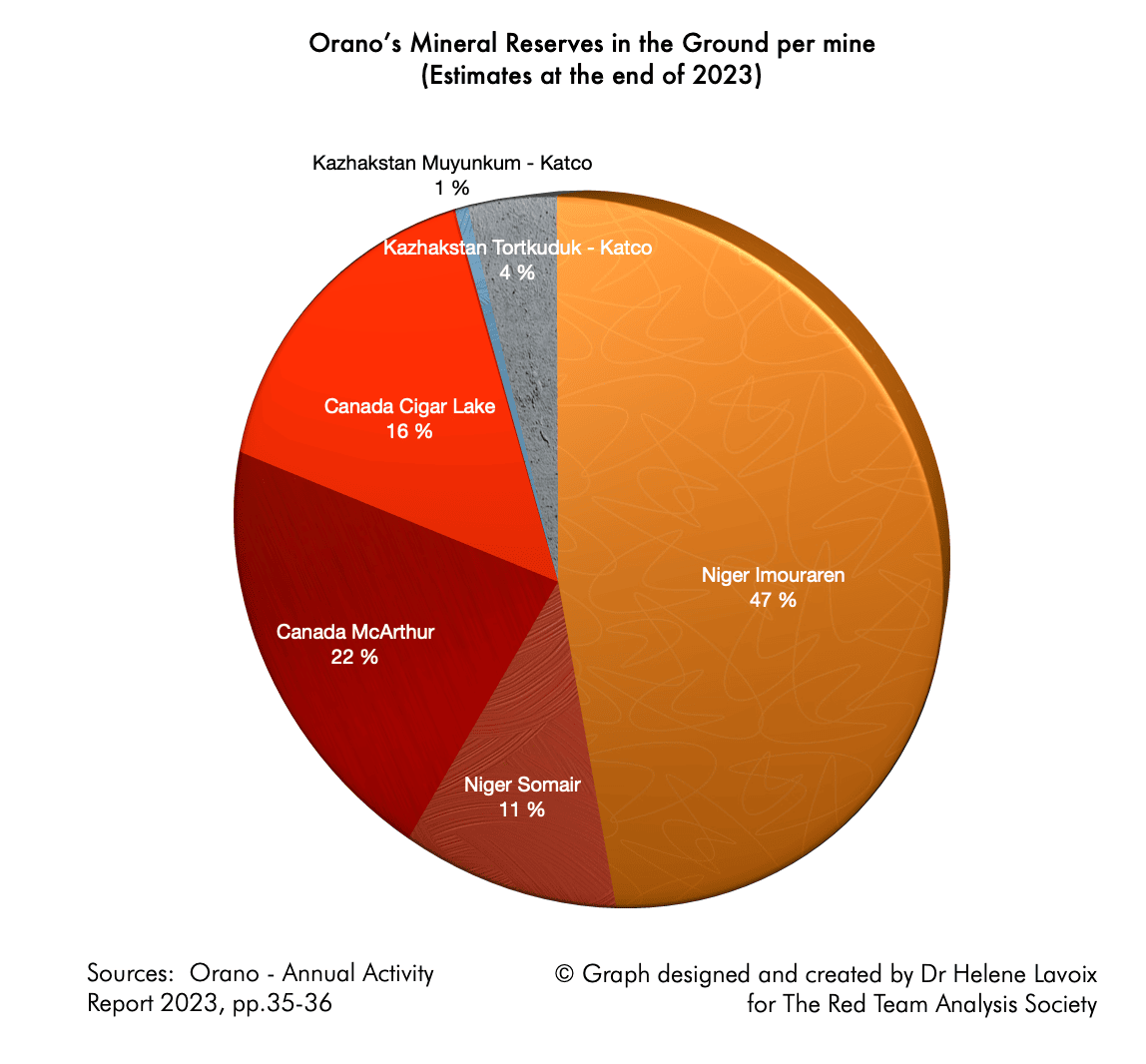

On 19 June 2024, Niger has revoked French nuclear state company Orano’s mining permit for the Imouraren mine. This means that Orano – and thus France – loses 47% of its uranium reserves, when an era of renewal for nuclear energy starts globally and when France plans to add between three pairs of EPR2 reactors, up to 14 and even 20 new EPRs to its current nuclear park (see below). What happened and what is at stake for France?

- Trump Geopolitics (2) – The US vs China Geoeconomic War

- AI at War (4): The US-China Drone and Robot Race

- How to use AI for Weak Signals – Trump, the International Revolutionary?

- 2d session of the Fifth Year of Advanced Training in Early Warning Systems & Indicators – ESFSI of Tunisia

- DeepSeek vs Stargate – China’s Offensive on U.S. AI Dominance?

- Trump Geopolitics – 1: Trump as the AI Power President

- Uranium for the U.S. Nuclear Renaissance – 2: Towards a global geopolitical race

France still is the second power worldwide in terms of nuclear energy generating capacity (Helene Lavoix, The Future of Uranium Demand – China’s Surge, The Red Team Analysis Society, 22 April 2024). Orano still is the third company globally for the nuclear fuel cycle (Helene Lavoix, Revisiting Uranium Supply Security – 1, The Red Team Analysis Society, 21 May 2024). As a result, France plays a leading role in the current global evolution towards the renewal of nuclear energy (Helene Lavoix, “The Return of Nuclear Energy“, The Red Team Analysis Society, 26 March 2024). Furthermore, nuclear energy is vital for the country, with nuclear power accounting for 62.6% of electricity in 2022 (IAEA-PRIS – 28/04/2024; Helene Lavoix, Revisiting Uranium Supply Security – 1, The Red Team Analysis Society, 21 May 2024).

However, uranium is needed to power nuclear plants. Despite appearances, France was well positioned in terms of uranium supply thanks to Orano’s overseas mining permits (Lavoix, Revisiting Uranium Supply Security – 1). Yet, as a result, French uranium security supply is also more fragile than it would be if uranium mines were located on its territory (Ibid.). Considering the specificity of France’s uranium supply, geopolitics and influence are key to secure that supply, as illustrates the catastrophe Orano now faces in Niger.

First, we address the situation in Niger and explain the threat now materialised surrounding Orano’s mining permit for Imouraren. As Niger’s Imouraren mine represents up to 47% of Orano’s uranium reserves and its loss will likely degrade France’s position globally as well as Orano’s, second, we focus on the stakes for France in terms of uranium supply and and underline the role that geopolitics plays now and in the future for uranium and thus nuclear energy.

Losing Orano’s Imouraren mining project in Niger

France loses its hold in the difficult political and geopolitical Nigerien context

Mining operations in Niger take place in a complex context.

The 26 July 2023 coup in Niger had multiple impacts (e.g. Gilles Yabi, “The Niger Coup’s Outsized Global Impact“, Carnegie Endowment for Peace, 31 July 2023). Notably, it soured greatly diplomatic relations between France and Niger. The French Embassy in Niger was closed on 2 January 2024 (French Ministry of Foreign Affairs). All French troops had to leave the country the end of December 2023, after France was similarly asked to leave Mali then Burkina Faso (France 24, “Last French troops leave Niger, ending decade of Sahel missions“, 22 December 2023).

The eviction of France from Sahel results from difficulties with the peace-keeping and stabilising missions there, then used by Russia against France as a consequence of France’s decision to side with the U.S. in Ukraine (e.g. Aja Melville, “Russia Exploits Western Vacuum in Africa’s Sahel Region,” Defense and Security Monitor, 22 April 2024). Russia retaliated strategically in a flanking manoeuvre, hitting France by further degrading its influence and replacing it in Sahel (e.g. Ibid., Fatou Elise Ba, “L’aide publique et humanitaire de la France n’est plus la bienvenue au Mali“, IRIS, 16 February 2023)

Meanwhile relations between Niger and the EU, the US, and the UN also strongly degraded, including with consequences for migrations towards Europe (Le Monde with AFP, “Niger ends EU security and defense partnerships“, 4 December 2023; Danai Nesta Kupemba , “US troops to leave Niger by mid-September“, BBC News, 18 May 2024; Stateswatch, “EU: Commission halts migration cooperation with Niger, but for how long?“, 07 September 2023; France 24, “Niger’s junta ends security agreements with EU, turns to Russia for defence cooperation“, 4 December 2023).

Thus, Russia’s influence is on the rise, as elsewhere in the region (e.g. Olumba E. Ezenwa and John Sunday Ojo, “Russia has tightened its hold over the Sahel region – and now it’s looking to Africa’s west coast“, The Conversation, 29 April 2024). For example, on 26 March 2024, the Russian President Vladimir Putin and the President of the National Council for the Safeguard of the Homeland of the Republic of Niger Abdourahamane Tchiani “expressed determination to step up political dialogue and develop mutually beneficial cooperation in various spheres” (Kremlin website). Then, in April 2024 military advisors from the ex-Wagner group renamed African Corps arrived in Niger’s capital Niamey (AFP, “Russian military instructors, air defence system arrive in Niger amid deepening ties“, France 24, 12 April 2024).

Meanwhile, Niger has to face complex jihadist insurgencies (e.g. Natasja Rupesinghe and Mikael Hiberg Naghizadeh, “Les djihadistes du Sahel ne gouvernent pas de la même manière: le contexte est déterminant“, The Conversation, 25 January 2022). Following the coup, it must also grapple with discontent asking for the return of ex-President Bazoum, including armed groups such as the Front patriotique pour la Libération (FPL), led by Mahmoud Sallah (e.g. Interview with Mahmoud Sallah, 21 May 2023; RFI, “Niger: le Front patriotique pour la Libération revendique l’attaque du pipeline,” 18 June 2024). Indeed, on the night of 16 to 17 June 2024, the FPL blew up the pipeline carrying Nigerien crude oil to the port of Cotonou in Benin (RFI, ibid.; FPL Facebook page).

Terminating Orano’s Imouraren operating permit

Despite this hostile context, in February 2024, Orano, through its subsidiary Somair, succeeded in re-starting mining in the region of Air in Niger (e.g. “Orano : arrêtée depuis le coup d’Etat, la production d’uranium redémarre timidement au Niger“, La Tribune, 16 February 2024).

However, on 11 June 2024, for the Imouraren project, “the mine of the future“, Orano, or rather its subsidiary Imouraren SA held at by 36,5 % by Niger, received a second formal notice, after the first issued on 19 March 2024, demanding operations at Imouraren be started in a way satisfying the country (Ahmadou Atafa, “Niger : Imouraren SA sous la menace imminente de perdre son permis minier“, Airinfo, 14 June 2024; MondeAfrique, “Niger, le groupe Orano pourrait perdre sa mine d’uranium“, 14 June 2024; Emiliano Tossou, “Le Niger veut retirer le projet d’uranium Imouraren au français Orano, Ecofin Mines, 18 June 2024). The latest plan for operations had been rejected on 7 June 2024 (Ibid.). Failure to comply would imply the termination on 19 June 2024 of the operating permit of Imouraren SA for the mines of Imouraren (Ibid.).

Yet, on 12 June, Orano had announced it was relaunching operations at Imouraren, but nothing had started on 13 June (Le Monde/AFP, “Au Niger, Orano a lancé les travaux préparatoires pour l’exploitation du gisement d’uranium d’Imouraren“, 12 June 2024; Atafa, “Niger : Imouraren SA…).

Meanwhile, Bloomberg mentioned rumours according to which ongoing negotiations would be taking place between the Russian nuclear company Rosatom and Niger’s military-political authorities to reallocate Orano’s uranium assets to Rosatom (for more on Rosatom, see Revisiting Uranium Supply Security – 1; Bloomberg News, “Russia Is Said to Seek French-Held Uranium Assets in Niger“, via Mining.com, 3 June 2024; Katarina Hoije, “Orano at Risk of Losing Niger Uranium Mine Sought by Russia“, BloombergNews via Mining.com, 15 June 2024).

After a day of silence, on 20 June, Orano issued a press communiqué stating that Nigerien authorities had decided “to withdraw its licence to operate the deposit from its subsidiary Imouraren SA”.

According to the communiqué Orano is ready to continue the discussion as well as to press the matter “before the competent national or international judicial bodies”.

What is at stake for France?

Current supply of uranium is not at stake as production has not yet started at the Imouraren mine.

The concern is for the future and depends on the potential of the mine. Obviously, the larger the uranium mine and the higher its yield, the higher the stakes.

Imouraren and uranium reserves for France

Now, Imouraren, discovered in 1966 by France, is not a small mine nor does it represent small reserves and resources for Orano and thus for France (for explanations on reserves and resources, Lavoix, Revisiting Uranium Supply Security – 1; Nuclear Energy Agency (NEA)/International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), Uranium 2022: Resources, Production and Demand (Red Book), OECD Publishing, Paris, 2023, p. 387). Quite the contrary.

Imouraren holds 145.712 tonnes of Uranium in reserves, out of which 95.527 were Orano’s share (2023 Orano Annual report, pp. 35-36). “Production was expected to be 5.000 tU/yr for 35 years” (NEA/IAEA Red Book 2022 p.388). For the sake of comparison, France yearly requirements in 2024 were 8.232 tU (WNA, “World Nuclear Power Reactors & Uranium Requirements“, May 2024). Imouraren could thus have covered alone 60,7% of France 2024 Uranium requirements. Exploiting Imouraren would thus have greatly facilitated projects to increase the number of nuclear reactors in France, as well as ensured trade revenues for Orano, considering other mines. Together, this would have secured Orano and France’s influence in the field.

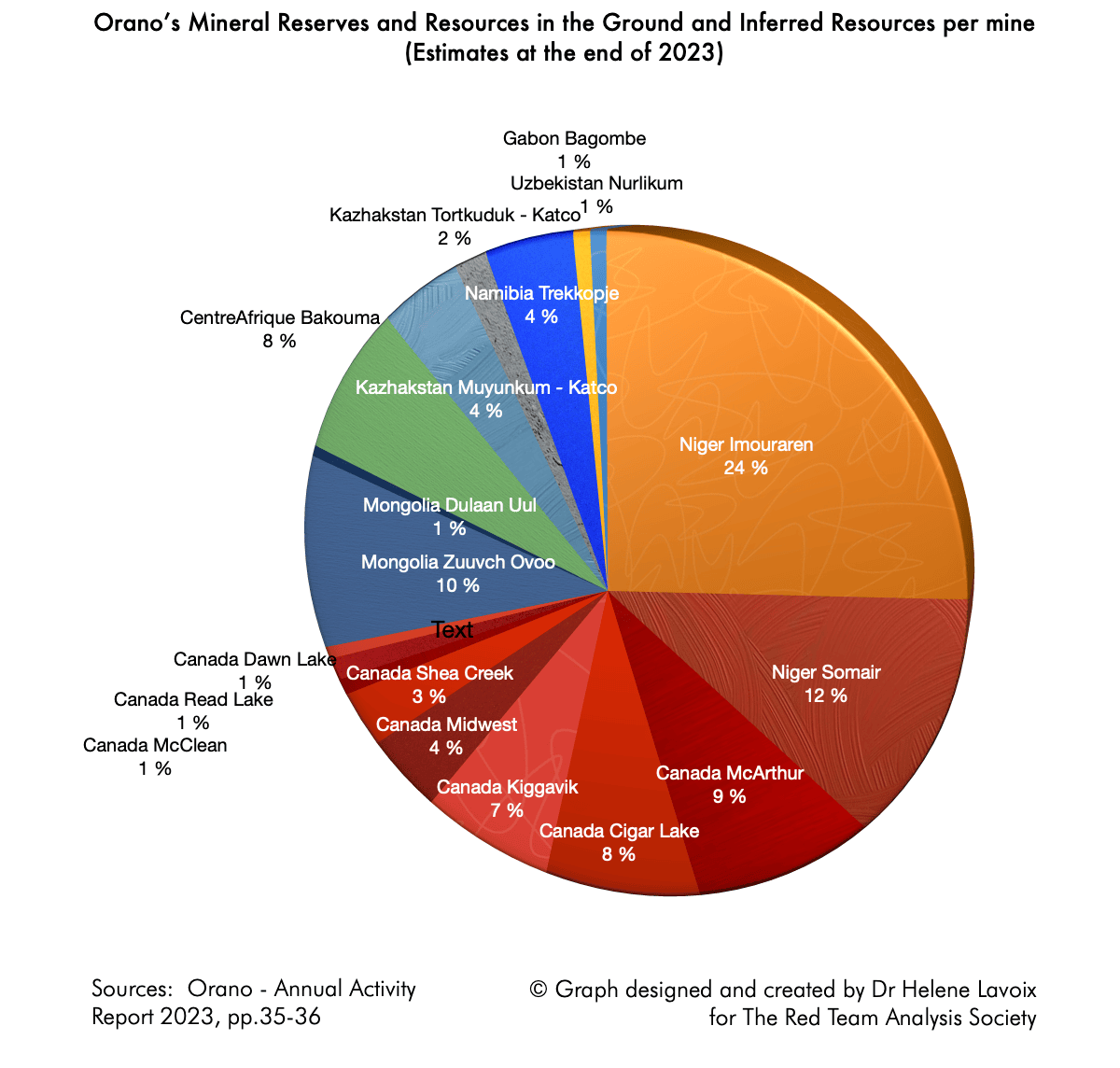

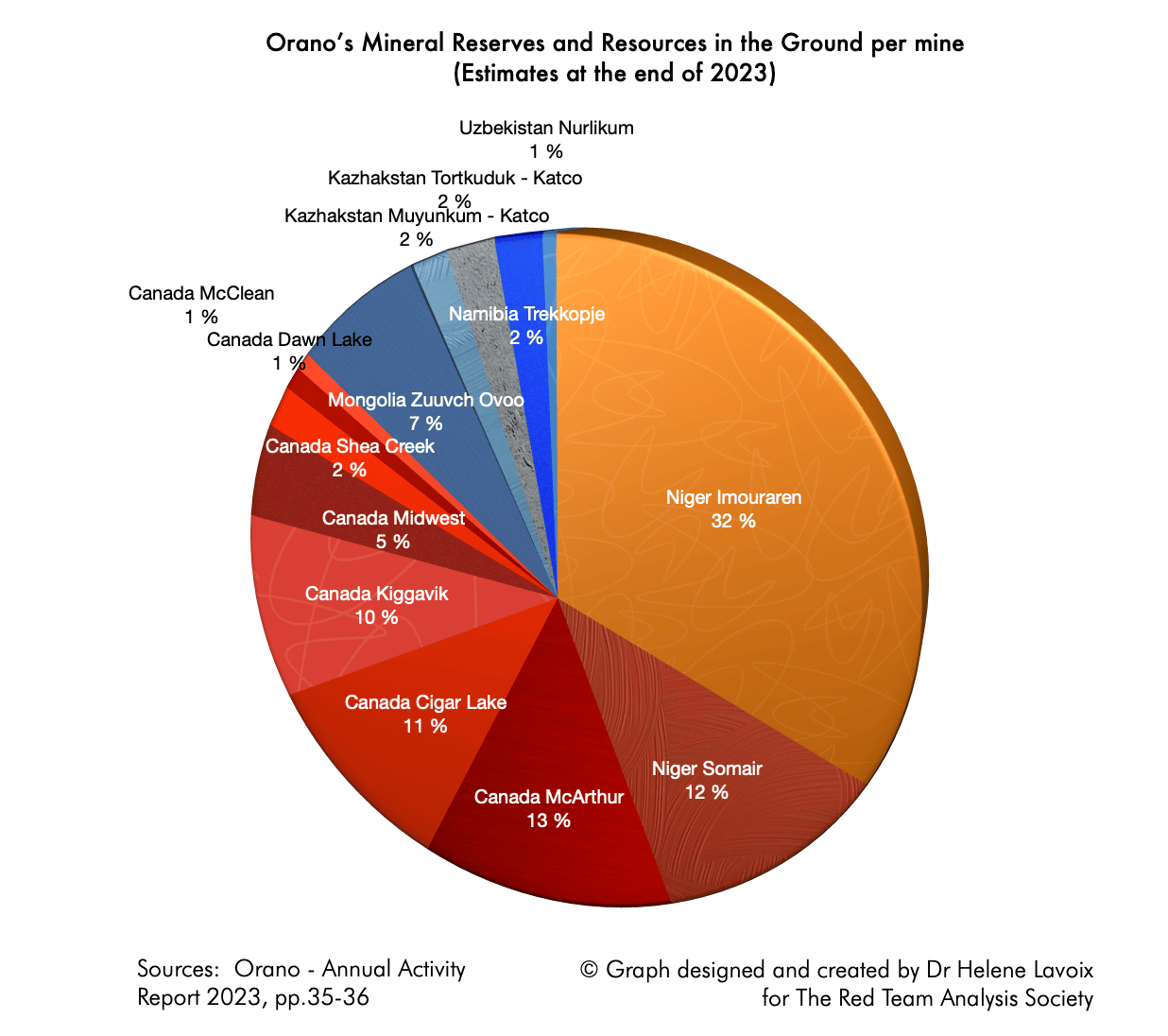

In terms of reserves, as shown on the series of charts below, the mine of Imouraren in Niger represents 24% of the total uranium reserves and resources in the ground plus inferred resources of Orano, i.e. the largest segment (in tonnes of Uranium, i.e. considering the varying yield of each mine). The share of Imouraren is larger if we only consider total reserves and resources in the ground, i.e. 32 %, and even larger if we only take into account reserves, i.e. 47%.

In other words, the further away we are in time, the more potential uranium supply outside Niger Orano holds. This is a tribute to the company’s exploration and diversification effort. Nonetheless, we should not forget the uncertainty weighing on Orano’s Mongolian supply since February 2024 (Lavoix, “The Return of Nuclear Energy“).

However, as far as medium term uranium supply is concerned, losing the mine of Imouraren creates a security challenge.

A threat on medium term supply considering plans for nuclear energy

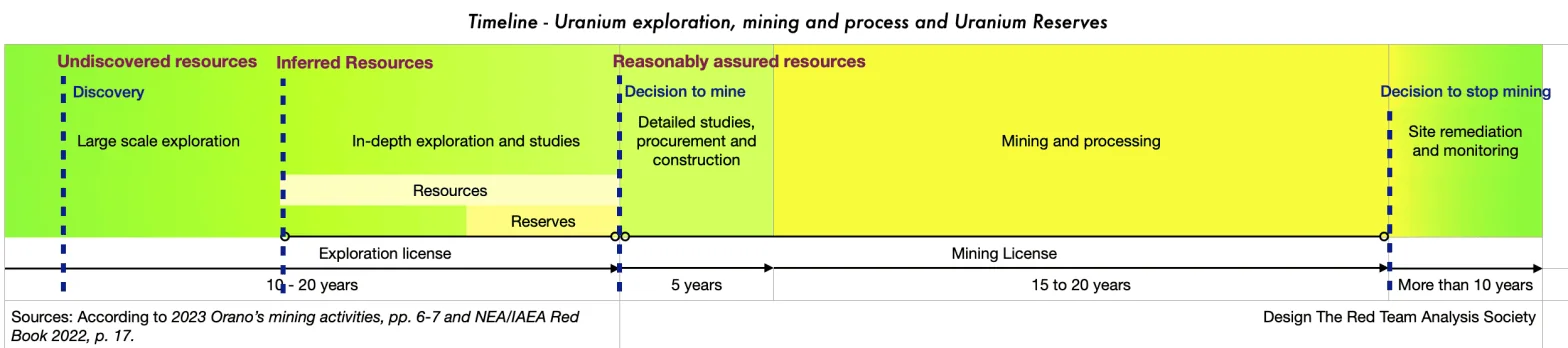

Indeed, changes in a mining portfolio introduce an uncertainty for the future that is all the more important that exploration to find mines, then feasibility studies then plans for operation, before mining and milling can start, are of the long period, as shows the figure below.

Currently, in line with the current objectives of renewal of nuclear energy, France plans to construct and connect to the grid between 6, 14 and even 20 new nuclear power plants.

For its part, in 2022, French President Macron finally asserted the key role of nuclear energy (Assemblée nationale, Rapport de la commission d’enquête visant à établir les raisons de la perte de souveraineté et d’indépendance énergétique de la France, 30 mars 2023). In January 2024, 8 more nuclear reactors were announced, on top of the 6 already programmed in 2022, which construction should start in 2028 for a first connection to the grid in 2035 (Euronews, “Macron calls for nuclear ‘renaissance’ to end the France’s reliance on fossil fuels” (sic), 11 Feb 2022; RFI, “France to build more new generation nuclear reactors to reach green targets“, 7 January 2024).

Meanwhile, the rising Rassemblement National, the principal opponent to President Macron’s party for the anticipated June 2024 legislative elections, is a staunch supporter of nuclear energy (programme RN European elections June 2024). For example, during the 2022 presidential and legislative campaigns, it envisioned the launch of 20 European/Evolutionary Pressurised Reactor (EPR) (François Vignal, “Energie : plein pot sur le nucléaire et haro sur les éoliennes pour Marine Le Pen“, Public Sénat, 14 March 2022); Alexandre Rousset, “Présidentielle : Marine Le Pen voit le salut de la France dans l’énergie nucléaire“, Les Echos, 14 March 2022).(1)

Finally, in the 3rd Programmation pluriannuelle de l’énergie (PPE), opened for concertation in November 2024, France plans to launch three pairs of EPR2 reactors with decision to invest to be taken by EDF by 2026 , to which should be added support to the development of Small Modular Reactors (SMR) (SFEN, “PPE 3 et SNBC 3 : neuf orientations pour le nucléaire français“, 4 November 2024). Meanwhile, the lifespan of existing reactors will be extended beyond 50 or even 60 years (Ibid.)

Thus, supplementary uranium requirements will be needed, starting approximately in 2035 (if the time needed to build and connect an EPR is approximately 9 years – see Towards a U.S. Nuclear Renaissance?), for yet unknown quantities. This means that by 2029-2030 latest, corresponding decisions to mine must be taken so that new production can start and be delivered in 2035. If ever EPRs were built faster then supplementary uranium requirements would occur earlier.

If France already has mining sites that are ready or quasi ready for the stage corresponding to the decision to mine, then all is well. Imouraren corresponds to this case. Indeed, Orano planned to start a pilot programme there in 2024, with decision to invest in 2028 “if feasibility is confirmed” (World Nuclear News, “Preparatory activities begin at Imouraren“, 17 June 2024).

If no mining site of this type is available, then Orano must rely on sites that are at the stage of in-depth exploration and studies. Because only four to five years are left until 2029/2030, then that means that in-depth exploration, which may last approximately 10 years, must have already started. However, compared with a site where in-depth exploration has already taken place, in that case, uncertainty is stronger.

Furthermore, mining permits will need to be requested and obtained in four to five years time, which heightens uncertainty stemming from geopolitics.

For example, Orano may very well see in-depth exploration yielding excellent results, but in an area where Russian influence is very strong and could be even stronger in four to five years. In such a case, the current international French position regarding Russia, if it remains as such in the future, strongly lowers the probabilities of Orano obtaining any mining permit.

Alternatively, accounting for strong competition over uranium resources, Orano may also lose mining permits to allies, which will have no qualm about thinking about their national interest first. For example, considering American needs in terms of uranium and the U.S. small size of overseas reserves, as the U.S. ranks globally 10 in terms of reserves and resources, it would not be surprising to see the U.S. using strong if not violent methods to secure uranium in the future (Lavoix, The Future of Uranium Demand and Revisiting Uranium Supply Security – 1). One should remember the American attitude when the stakes were face masks during the COVID 19 pandemic or the way the U.S. stole from France the Australian contract for submarines (e.g. Ouest France “Coronavirus. En Chine, une cargaison de masques destinés à la France détournée par des Américains“, 2 April 2020; Helene Lavoix, “The American National Interest“, 22 June 2022).

Similar geopolitical insecurity weighs on exploration licenses to be obtained, as well as on those already granted, as the loss of Imouraren shows.

The threat in a global perspective

Considering the current and future appetite for uranium, what does mean the loss of Imouraren for France in a global perspective?

Taking into account the international context in the Sahel and more particularly in Niger, in the framework of the war in Ukraine, we make the hypothesis that the Imouraren mine permit will be granted to Russian Uranium One through Rosatom in the same conditions as what existed for Orano (same shares – for Uranium One, see Lavoix Revisiting Uranium Supply Security – 1). This hypothesis is increasingly likely considering the 8 November statements of the Nigerien Mining Minister Ousmane Abarchias, according to which “Niger is actively seeking to attract Russian investment in uranium and other natural resources” (RFI, “Niger embraces Russia for uranium production leaving France out in the cold“, 13 November 2024).

We use as basis the graph we developed previously to revisit the security of uranium supply by integrating overseas efforts by mining companies. The data in the graphs comes from extensive research carried out for The World of Uranium: Mines, States, and Companies – Database and Interactive Graph. The initial graph is presented on the left-hand side. We then show the same graph without Imouraren for France, and without the Madaouela deposit for Canada (Canadian GoviEx Uranium Inc. having lost its mining permit on 4 July 2024). In a third graph on the right-hand side, we attributed as scenario the two deposits to Russia.

Comparing the graphs, France falls from 8th to 11th place, behind China, the U.S. and Brazil, and the EU from 7th to 9th place, whilst Russia takes 3rd place, before Kazakhstan, with a large increase in its overseas reserves and resources. Japan goes from rank 14 to rank 15, as two Japanese companies hold stake in French Orano.

Not only is the security of uranium supply degraded, but France’s weight in the world in terms of uranium supply is lessened. Considering future uranium demand this will have a negative commercial impact while diminishing the global influence of both Orano and France.

Knowing that supplying France nuclear power plants is a very important stake considering the French share of nuclear electricity, and that the global development of nuclear energy, notably stemming from China, will intensify global competition, the loss of Imouraren is very bad news.

The challenges met by Orano to export existing production from the Nigerien Somair (Société des mines de l’Aïr) Mine further darkens prospects and fragilise France’s uranium security (Benjamin Mallet, “Orano : Des provisions liées au Niger plombent les résultats du premier semestre“, Usine Nouvelle, 26 July 2024).

Indeed, as an update (7 November 2024), since the article was initially written, matters got worse between Orano and Niger. Following growing difficulties impacting Somair (63.4% held by Orano), including an inability to export production, and debts of Nigerien Sopamin (holding 36.6% of Somair) owed to Somair, Orano decided “to suspend its [Somair] activities, as an interim measure, as of the end of October” 2024 (News, “Niger: growing financial difficulties will force SOMAÏR to suspend operations“, Orano, 23 October 2024). In response, ignoring its own responsibility and decisions, Niger, through Sopamin attacked Orano’s decision, reportedly having been neither consulted nor informed. Niger offered to buy 210 t uranium out of the 1000 t held by Somair to help the company to continue its activity. Meanwhile, Niger repeatedly accuses France to carry out overt and covert operations against Niger (e.g. La Tribune, La France déstabilise-t-elle le Niger ?, 3 August 2024; Mathieu Olivier, “La DGSE française dans la tourmente après les accusations du Niger“, Jeune Afrique, 6 November 2024).

The tug of war between France, Orano and Niger goes on. As a result, it is now 58% of overseas French reserves of uranium (44 % of reserves and resources) that have disappeared or are disappearing compared with December 2023. Meanwhile, closing Somair means that the 2000 t U a year that were produced will not be anymore, i.e. for France’s share 1268 t U. This represents approximately 15.4% of France’s yearly requirements in uranium.

In the future, it appears as essential that international relations and foreign policy decisions be taken while also considering nuclear and uranium security, including on the longer term. This means that anticipation becomes even more important than what was already highlighted in the 2023 Rapport de la commission d’enquête of the National Assembly.

Meanwhile, the impact of Orano’s operations on domestic politics in country where it operates, as well as on regional and global geopolitics, must also be integrated into assessments, planning and policy. For example, known adverse dynamics such as the “resource curse” should always be assessed and integrated into analysis to make sure the right strategy to secure permits and operations is designed and implemented (e.g. Mähler, Annegret (2010), Nigeria: A Prime Example of the Resource Curse? Revisiting the Oil-Violence Link in the Niger Delta, GIGA Working Papers, No. 120, German Institute of Global and Area Studies (GIGA), Hamburg).

Our point is not that Orano causes or has caused such adverse dynamics, but that the possibility it happens should be envisioned and taken into account if the risk exist.

Potentially, policies to avert such negative consequences could also be developed, if adequate. Furthermore, such an approach could also reassure host governments and become an argument for influence.

The resource curse theory suggests that countries rich in natural resources, particularly oil and minerals, often experience slower economic growth, weaker democratic institutions, and greater political instability compared to resource-poor nations. This paradox arises from the disruption of fundamental political, societal and economic dynamics that typically balance governance.

One critical breakdown is in the “taxes-for-security exchange” dynamic. In all countries, ideally, political authorities rely on taxation to finance their activities, creating a direct relationship with citizens: governments provide security, public goods, and services in exchange for tax revenues. This dependence fosters accountability, as citizens demand responsible governance in return for their contributions. When the relationship functions, notably, legitimacy is strengthened. These dynamics appear to be naturally at work in resource-poor nations.

In resource-rich nations, however, governments often finance themselves through resource rents (profits from resource extraction), reducing their reliance on taxation. This weakens the social contract between rulers and the governed: the rulers have no interest in providing security to their citizens as their resources do not come from taxes and, as a result, the ruled live in insecurity and are less empowered to hold political authorities accountable. Political authorities become increasingly illegitimate domestically but remain in power out of the support of those benefiting from the resources, most often external to the polity.

Finally the new insecurity on French uranium supply stemming from the loss of Imouraren in Niger, and the tug of war surrounding Somair, highlights a difficult question: Is it secure for France to have a foreign policy that is not one of independence and non-alignment (e.g. Pascal Boniface, “Why the Legacy of De Gaulle and Mitterand Still Matters for the French Public Opinion“, IRIS, 15 March 2021; The Non-Aligned Movement“, Wikipedia).

France’s national interest, with uranium supply at the top of the agenda considering the importance of nuclear energy for the country and the world, should be sought first, before any other point. This may be what the November 2023 and November 2024 reciprocal state visits between France and Kazakhstan, a major supplier and partner in terms of uranium for France, indicate (Elysée, Visite d’État de son Excellence Kassym-Jomart Tokaïev, Président de la République du Kazakhstan, République Française, 5 November 2024; “Kazakhstan’s Tokayev in France: It’s All About Nuclear Energy“, The Times of Central Asia, 6 November 2024). The price to pay for another type of foreign policy could be very high indeed in terms of influence and power and ultimately in terms of uranium thus energy and finally access to electricity in the country.

Conclusion

The importance of politics and geopolitics for uranium supply is once more demonstrated in Niger.

Despite appearance the development of nuclear energy cannot remain the sole preserve of R&D, engineering and industrial planning. Succeeding in securing uranium supply when this security depends on overseas resources will demand to attribute the highest priority to the understanding of international relations and geopolitics and to the design and implementation of strategy. Influence and power, diplomatic acumen, and skilful, bold and original international actions, will become even more essential as the volatile international context unfolds and as the international impact of the renewal of nuclear energy spreads.

Notes

(1) During the 2022 presidential then legislative elections, at a press conference, Marine Le Pen – ex-president of the party and president of the RN group at the Assemblée nationale – stated that, within the framework of a plan for energy called “plan Marie Curie”, “five pairs of EPR” would be launched for 2031″ and “five pairs of EPR2” for 2036 (François Vignal, “Energie : plein pot sur le nucléaire et haro sur les éoliennes pour Marine Le Pen“, Public Sénat, 14 March 2022); Alexandre Rousset, “Présidentielle : Marine Le Pen voit le salut de la France dans l’énergie nucléaire“, Les Echos, 14 March 2022).

Leave a comment