(Art direction and design: Jean-Dominique Lavoix-Carli)

On 21 March 2024, thirty two heads of states and governments and special envoys met in Brussels for a summit that received little media attention, despite a very high level attendance. This meeting was the first ever Nuclear Energy Summit, jointly hosted by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) and Belgium (IAEA Website).

Why is nuclear energy coming back on the agenda and why such a high level interest? What did leaders decide and which leaders? Could the renewal of interest in nuclear energy entail new geopolitical challenges? These are questions this article explores and answers, taking as example in terms of geopolitics and energy security the case of the Franco-Mongolian € 1.6 billion deal for uranium.

Why nuclear energy increasingly matters

Keeping our way of life while reducing GHG emissions means nuclear energy

- Niger: a New Severe Threat for the Future of France’s Nuclear Energy?

- Revisiting Uranium Supply Security (1)

- The Future of Uranium Demand – China’s Surge

- Uranium and the Renewal of Nuclear Energy

- AI at War (1) – Ukraine

- Anticipate and Get Ready for the Future – Podcast

- The Return of Nuclear Energy

- Climate Change, Planetary Boundaries and Geopolitical Stakes

Energy is a fundamental element of life. Energy is key for the development of all the activities that underlie a civilization. Thomas Homer-Dixon highlighted that is was a master resource (The Upside of Down: Catastrophe, Creativity and the Renewal of civilization, Knopf, 2006). Energy is indeed present and indispensable from every step of the food chain – food being itself energy – to transportation, industry, trade and availability of goods, defense, etc.

The amount of energy human life and its civilizations use – excluding food – is measured as the world final energy consumption. In 2022, this world final energy consumption represented 442,4 EJ (Exajoules), a 1,7% increase compared with 2019. To allow this demand to be met, the world had to supply globally 632 EJ in 2022 (International Energy Agency (IEA), World Energy Outlook 2023, October 2023; IEA, Net Zero by 2050 – A Roadmap for the Global Energy Sector, May 2021). Renewables (solar, wind, hydro, modern solid, liquid and gazeous bioenergy) represented only 11,7% of the energy supply, while together, oil, gas and coal represented 79,4% of the energy supply.

At the same time, climate change is increasingly obvious, and threatens human ways of life. Hence, there is an absolute necessity to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, the culprit for climate change.

As governments and populations wish, as much as possible, to keep their model of civilizations, and as the way we produce energy is a major cause of GHG emissions, then human beings must rethink the very production of energy.

Considering the challenge of GHG emission and civilizational constraints, in 2021, the International Energy Agency (IEA) created a scenario for the world energy sector that would allow reaching net zero emissions (NZE) by 2050: Net Zero by 2050 – A Roadmap for the Global Energy Sector. It included in its scenario efforts to make some relatively minor behavioural change and to develop new technologies such as carbon capture, utilisation and storage (CCUS), but fundamentally the scenario is about changing our way to produce energy. The IEA slightly revised the data used with the publication of the World Energy Outlook 2023, but the logic and the scenario remain the same.

In this scenario, global demand for energy must decrease to 406 EJ final energy consumption in 2030 and to 343 by 2050, with a substantial increase in the share of electricity in this global demand (IEA, World Energy Outlook 2023). The latter must represent 53% of global energy demand in 2050, when it represented 20% in 2022 (Ibid.).

Correspondingly, the supply energy mix must change.

Thus, not only renewables, but also nuclear energy must increase, while other energy sources must decrease until 2050. Renewables must represent, respectively for 2030 and 2050, 29% then 71% of the energy supply, and nuclear 7,5% then 12,4% (Ibid.).

This means reverting the trend towards moving away from nuclear energy, which was notably triggered by the 2011 accident at the Fukushima-Daiichi plant in Japan, after the 1986 Chernobyl disaster.

Indeed, according to the IEA scenario, continuing using nuclear energy and increasing nuclear power generation is key to see the NZE scenario being successfully achieved. The international body estimated that a “Low Nuclear and CCUS case” would make the transition far more costly and less likely (IEA, Net Zero by 2050, p.120). If the “global nuclear power output were 60% lower in 2050 than in the NZE” – i.e. approximately 24,4 EJ – then the IEA estimates the added cost in investments to USD 2 trillion and the added cost of electricity to consumers between 2021 and 2050 to USD 260 billion.

As a result, if we want to keep the same type of civilization, not only nuclear energy must be kept but it must be drastically developed.

Doubling the nuclear energy capacity by 2050?

If we consider the IEA NZE scenario, how does that translate in terms of nuclear energy capacity?

On 1st January 2021, the world counted 442 commercial nuclear reactors operating and connected to the grid in 31 countries, while 52 reactors were under construction (Nuclear Energy Agency (NEA)/International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), Uranium 2022: Resources, Production and Demand – also called “Red Book“, p. 99). The 2021 net energy generating capacity was of 393 GWe (Gigawatt electrical) requiring about 60.100 tU/y (tonnes of uranium per year) (Ibid. p. 12). As a result, in 2020, about 2.523 TWh (Terawatt hours) were generated (Ibid.).

The IEA, for its part, estimates this amount to 2.698 TWh, corresponding to 29 EJ (IEA, Net Zero by 2050…, Annex A, Tables for scenario projections).

The IEA NZE 2050 scenario plans that nuclear electricity production should reach 3.777 TWh by 2030, 4.855 TWh by 2040 and 5.497 TWh by 2050 (ibid., p. 198). It estimates that the corresponding nuclear net generating capacity should be 515 GWe in 2030, 730 GWe in 2040 and 812 GWe in 2050 (Ibid. p. 198).

If we follow the figures in the “Red Book” and use them for the IEA NZE scenario, then nuclear electricity production should reach 3.532 TWh by 2030, 4.540 TWh by 2040 and 5.140 TWh by 2050. Everything being equal, this would translate in a nuclear net generating capacity of 550 GWe in 2030, 707 GWe in 2040 and 800 GWe in 2050.

In both cases, the IEA NZE 2050 scenario demands doubling the nuclear energy capacity by 2050.

States and industry step in to trebling nuclear energy capacity by 2050

However, according to the NEA, “the average IPCC 1.5°C scenario requires nuclear energy to reach 1.160 GWe (gigawatts electrical) by 2050 (NEA, Meeting Climate Change Targets: The Role of Nuclear Energy, OECD Publishing, 2022, Paris, p. 33).

It is this figure the NEA took as objective for the new nuclear energy capacity (Ibid.).

This means almost tripling the current world nuclear capacity by 2050, and not “only” doubling it.

The “Declaration to Triple Nuclear Energy by 2050”

The objective to triple the current nuclear capacity was supported by the World Nuclear Association (WNA), the international organisation representing the global nuclear industry. In September 2023, the WNA and the Emirates Nuclear Energy Corporation, as founders, supported by the IAEA, launched an advocacy effort, “Net Zero Nuclear”, ahead of the 28th United Nations Climate Change Conference or Conference of the Parties of the UNFCCC (COP28), that:

“Calls for unprecedented collaboration between government and industry leaders to at least triple global nuclear capacity to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050.”

NZN website

Among the main partners of the advocacy effort, we find the China National Nuclear Corporation (CNNC) and the Americano-Japanese alliance GE Hitachi Nuclear Energy.

Then, on 2 December 2023, at the COP28 in the United Arab Emirates, the trebling objective was officially endorsed. There, French President Emmanuel Macron and American Special Envoy John Kerry announced the “Declaration to Triple Nuclear Energy by 2050” (Présidence de la République Française, official text, 2 Dec 2023), signed by 22 countries that thus showed their commitment to make efforts to reach this goal (Nuclear Energy Agency, “COP28 recognises the critical role of nuclear energy for reducing the effects of climate change“, 21 December 2023).

The 22 signatories of the “Declaration to Triple Nuclear Energy by 2050” were Bulgaria, Canada, the Czech Republic, Finland, France, Ghana, Hungary, Japan, Moldova, Mongolia, Morocco, the Netherlands, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, South Korea, Sweden, Ukraine, the UAE, the United Kingdom and the United States (ISHII Noriyuki, “22 Countries Sign Declaration to Triple Global Nuclear Energy Capacity“, JAIF News, 2 December 2023).

China and Russia were thus initially not part of the signatories, despite their growing role in nuclear generation. For example, 27 of the 31 reactors built since 2017 are of Russian or Chinese design (IAE, Nuclear Power and Secure Energy Transitions, p.15).

A couple of days later, on 5 December, the nuclear industry followed suite. “120 companies, headquartered in 25 countries, and active in over 140 nations worldwide” endorsed the Net Zero Nuclear Industry Pledge (Press statements, “Net Zero Nuclear Industry Pledge sets goal for tripling of nuclear energy by 2050“, 5 December 2023). At industry level Russia through Rosatom was part of the signatories. However, neither the CNNC, although having supported the initiative, nor the China General Nuclear Power Group (CGN) signed the pledge.

Unsurprisingly, geopolitics and national interest are also part of the agenda.

The First Nuclear Energy Summit

To follow suite on the “Declaration to Triple Nuclear Energy by 2050”, and as promised in December 2023, governments and international agencies convened the first Nuclear Energy Summit on 21 March 2024.

In the run up to the 21 March Summit, as they prepared it, the members of the European Nuclear Alliance (Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Finland, France, Hungary, the Netherlands,Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia and Sweden), created on 28 February 2023, reasserted their commitment to nuclear energy alongside renewable energies (Declaration of the EU Nuclear Alliance – Meeting of March 4th, 2024).

Finally, 33 countries attended the Nuclear Energy Summit, from the initial 22 countries involved in the December 2023 declaration, and signed the new “Nuclear Energy Declaration” (Belga News Agency, “Nuclear declaration adopted by over 30 countries at first nuclear energy summit“, 21 March 2024; 32 countries by some accounts, e.g. “Leaders commit to ‘unlock potential’ of nuclear energy at landmark summit“, World Nuclear News, 21 March 2024):

“We, the leaders of countries operating nuclear power plants, or expanding or embarking on or exploring the option of nuclear power … reaffirm our strong commitment to nuclear energy as a key component of our global strategy to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from both power and industrial sectors, ensure energy security, enhance energy resilience, and promote long-term sustainable development and clean energy transition….”

Extract from the Summit Declaration, “Leaders commit to ‘unlock potential’ of nuclear energy at landmark summit“, World Nuclear News, 21 March 2024

Unsurprisingly, the nuclear industry also endorsed the declaration (Industry Statement pdf).

We are thus entering a totally new era for nuclear energy, compared with years of disengagement and fear.

Towards a geopolitics of nuclear energy?

In terms of international relations, in 2024, China joined the signatories, but Russia was still not part of them (e.g. CGTN, President Xi’s special envoy to attend first nuclear energy summit in Brussels; Nuclear energy declaration adopted at Brussels summit).

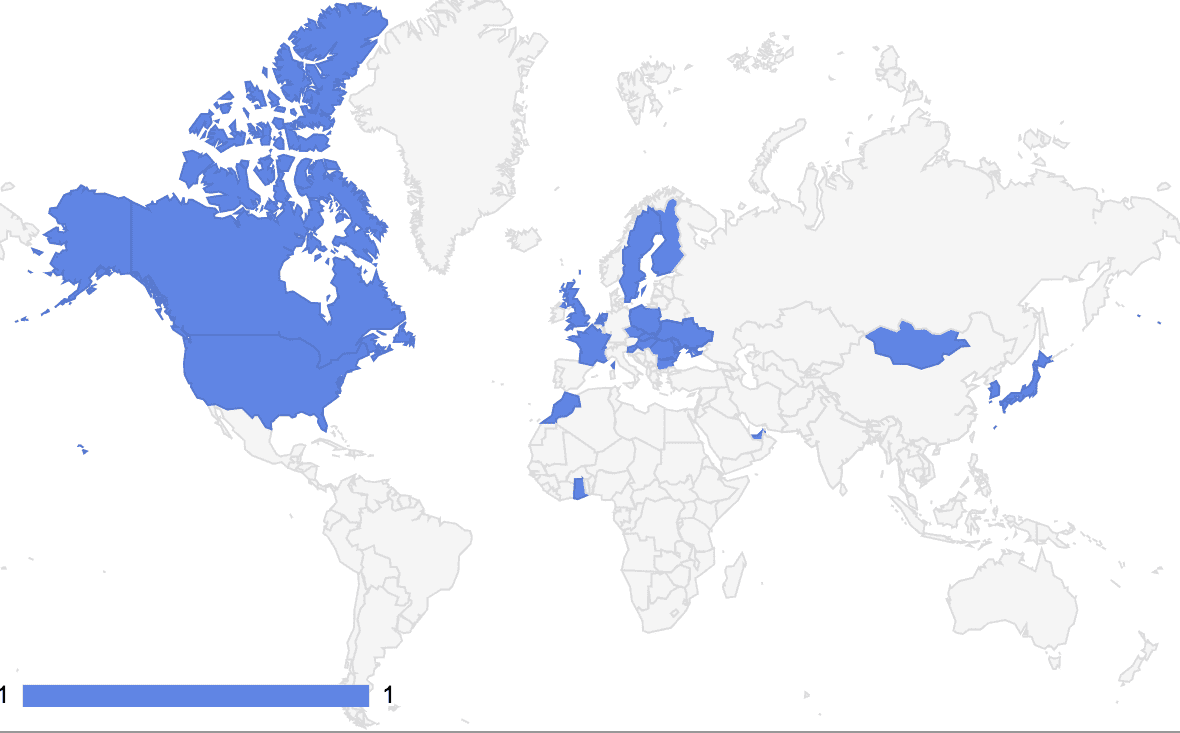

Interestingly, if in March 2024 some countries joined the new nuclear effort, some of the countries that had signed the initial declaration were not present in Brussels. The reasons for their absence may be multiple, some of them simple and with no geopolitical component. Yet, those countries were signatories of the 2023 declaration and not of the 2024 one. We represented the evolving participation in the map below:

Signatories of the Nuclear Energy Declarations 2023 and 2024 – Signatories of the 2023 “Declaration to Triple Nuclear Energy by 2050”, as founding members, were given a 3, signatories of the 2024 declaration were given a 1. The signatories of both declarations therefore receive a 4.

Mongolia, notably, did not joint fellow states in 2024, despite holding significant amount of reserves of uranium, having signed nuclear cooperation agreements with, for example, India in 2009 and France in 2010, and planning to develop nuclear power (e.g. World Nuclear Association, “Uranium in Mongolia“, September 2022).

Yet, in October 2023, following the first ever visit of a French President to Mongolia in May 2023, when Mongolian President Ukhnaagiin Khurelsukh was in Paris for a three-day state visit, France and Mongolia signed a € 1.6 billion deal, which would notably include mining of uranium by French Orano – one of the leading international nuclear industrial actor (Le Monde/AFP, “Emmanuel Macron en visite en Mongolie, une première pour un président français“, 21 May 2023; Mailys Pene-Lassus, “Mongolia opens way for uranium mining with $1.7bn French deal“, Nikkei Asia, 13 October 2023).

This deal is part of French efforts at diversifying its supply of uranium, which is fundamental for the country’s security.

Indeed, considering that 70% of French electricity comes from nuclear energy, that France’s supply of uranium originated in 2022 from five main sources according to Euratom – Kazhakstan 37,3%, Niger 20,2%, Namibia 15,8%, Australia 13,9% and Uzbekistan 12,9% – and that French relations with Niger are at best tense following the coup d’Etat, even though Orano only highlighted a delay in operations, mining restarting indeed in February 2024, it is key for France to diversify its supply of uranium (World Nuclear Association, “Nuclear Power in France“, March 2024; Euratom cited in Assma Maad, “A quel point la France est-elle dépendante de l’uranium nigérien ?“, Le Monde, 3 August 2023; Olanrewaju Kola, “Niger severs diplomatic ties with Nigeria, France, US, Togo“, Anadolu Agency, August 2023; Laura Kayali, “France closes embassy in Niger“, Politico, 2 January 2024; “Orano : arrêtée depuis le coup d’Etat, la production d’uranium redémarre timidement au Niger“, La Tribune, 16 February 2024).

Furthermore, when the coup in Niger had already increased French insecurity in terms of uranium supply, Kazakhstan warned in January 2024 it could have to reduce its production forecast (Ibid.), which was confirmed in March 2024 (Colin Hay, “Global uranium supply in jeopardy as Kazatomprom lowers production forecasts“, Small Caps, 18 March 2024).

As a result, the diversification of uranium supply became even more important.

Unfortunately, on 22 February 2024, information surfaced that the Franco-Mongolian deal was facing challenges and could be postponed until June (Bloomberg News, “France’s $1.6 billion uranium deal with Mongolia faces delays“, Mining.com, 22 February 2024).

Knowing that Russia supplies more than 80% of the petroleum products needed by Mongolia, and that Russia “had to” “cut energy supplies to its neighbour” in December leading to rationing (Ibid.), and considering the tense relations between U.S. allies and Russia, including as a result of the war in Ukraine, we may make the hypothesis that Russia’s actions and Mongolia’s dependence on Russia played a part in the setback impacting the Franco-Mongolian uranium deal.

France’s uranium supply is thus under threat and the country sees one of its efforts at diversifying its supplies potentially undermined, at best delayed. We cannot ignore that Russian influence may have played a part in these hurdles. Although firmer evidence would be needed here too, we may nonetheless wonder in which way these challenges related to the supply in uranium and thus to nuclear energy did not play a part in the new, harsher approach on Russia taken by France on 27 February 2024 (e.g. Le Monde & AFP, “War in Ukraine: Macron doesn’t rule out sending Western troops on the ground, announces missile coalition“, Le Monde, 27 Feb 2024).

This case study, although involving many hypotheses, highlights how the new era for nuclear energy, as ushered by the two international 2023 and 2024 declarations, will also come with new geopolitical challenges and tensions, as states seek to reduce the potential for insecurity.

When studying and developing policy recommendations for the trebling of nuclear energy capacities, international agencies stress the various challenges ahead, focusing on “cost, performance, safety and waste management” (IEA, Nuclear Power and Secure Energy Transitions, 2022; NEA, Meeting Climate Change Targets: The Role of Nuclear Energy, OECD Publishing, 2022, Paris, pp.39-46). The March 2024 Nuclear Energy Summit emphasised, among others, the complexity of financing the heavy investments in nuclear energy (e.g. Nuclear Energy Summit 2024’s Programme; Nuclear newswire, “Nuclear Energy Declaration adopted at Brussels summit“, 22 March 2024).

Furthermore, as the case study above highlights, challenges could also stem from uranium mining and milling as exploration and industrial process converges with geopolitics.

In future articles, we shall thus focus on those challenges the world is likely to face to fuel nuclear energy’s new development, i.e. uranium mining and milling in the unsettled world of international politics.

“This case study, although involving many hypotheses, highlights how the new era for nuclear energy, as ushered by the two international 2023 and 2024 declarations, will also come with new geopolitical challenges and tensions, as states seek to reduce the potential for insecurity.”

Excellent analysis of a complex geopolitical issue. Always a treat to read her views on any issue.

Dear Shahid Husain,

Thank you so much for the compliment!

Helene