In 2013, the Syrian civil war is more than two years old and, according to the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, would have claimed the lives of more than 60.000 people (until November 2012), while 1.2 million fled to neighbouring countries and 4 million were internally displaced (AFP, 4 April 2013). The Syrian war is a challenging problem for strategic foresight and warning because, besides the humanitarian disaster, the risks to regional and global peace and stability continuously increase, because the conflict is redrawing the strategic outlook of the region while participating into the global paradigm shift, and, finally, because the fog of war makes our anticipatory task more difficult and complex. We shall address those issues in a series of posts on the war in Syria and emerging potential futures.

We are facing three – related – sets of problems. First, we must deal with the war itself, where three, four or five types of Syrian actors and their “international backers” – or even more according to typologies, as we shall discuss below – and not two, fight for power. Second, we must prepare for the following peace while, third, evaluating and considering the still being redesigned strategic environment. Their specific characteristics will depend upon the length of the war, how it is waged and the way it ends. The peace should be prepared to be made constructive, positive, and lasting, and the strategic environment conducive to interests.* Getting ready for the second period and succeeding there starts with actions taken during the war and with the fate of the war itself, according to three main scenarios (leading to ten sub-scenarios) grounded in the current state of play.

To be able to use these scenarios for warning, regularly revisions should include what is happening on the ground. Methodologically, ongoing monitoring of the situation and related updating of scenarios may be the only way forward to deal with the fog of war.

Understanding the current state of play and the actors

Before to present the actors (click here), it is necessary to make two preliminary remarks.

1- Interestingly, in many analyses and reports on the war in Syria, one finds mention of only two or three groups of actors: the regime of Bashar al-Assad and the insurgency, to which are sometimes added the Kurds in Syria, who initially sat in an almost neutral position. Save for a few more detailed studies, which show how much more complex the situation is, “the insurgency” tends to be taken either as a broad umbrella label, or, more worryingly, as a monolithic bloc. A few interacting factors are probably at work here to explain this approach:

- We are faced with cognitive biases, or more specifically with the problem of enduring cognitive models in the face of new evidence, when the initial model was created early and with very few available evidence (Anderson, Lepper, and Ross, 1980). The tendency of our human brain to also overestimate “intentional centralized direction and planning” (Heuer, chapter 11, bias 2) is also probably at play.

- The difficulty to get information on the ground makes it even more complex to obtain reliable evidences that would ease our understanding of the situation on the battlefield. We should nevertheless underline, as noted in a recent EAworldview article, that the civil war in Syria is redefining how we get to know what is happening in the case of war, and it is thanks to the dedication of many, to a real crowdsourcing effort, and to the web and communication technologies that knowledge of the situation emerges. Compare, for example, with our blindness in past situations such as Cambodia. However, this also casts everyone in the role of collector of information and analyst (intelligence and scientific research roles), for which s/he has not been trained and that must be learned by trial and errors.

- Most probably, observers and analysts need to face conscious and unconscious deception and manipulation by fighting actors on the ground. Each group of fighters has an aim, as well as its own unconscious biases and partial vision and understanding of the situation. The story of each group, of each battle, be it told through written or video means or through interviews will reflect specific perceptions and goals, which must also be considered. The difficulty is very well underlined in the introductory paragraphs of a recent article by Matthew Barber on the excellent Syria Comment of Joshua Landis when he uses the new Syria Video facility to analyse “The Raqqa Story: Rebel Structure, Planning, and Possible War Crimes.”

- As a result, analysts are also actors in the Syrian war.

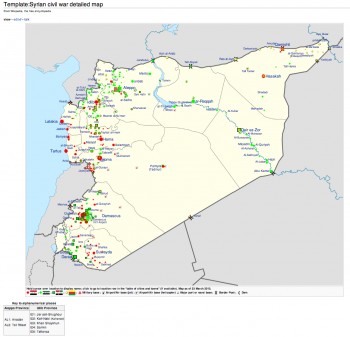

Furthermore, most of the time, the maps available in open source – however impressive the amount of details found on them, which is furthermore regularly updated (as the Wikipedia map shown here which describes the situation in Syria as of 23 March 2013) – only communicate part of the picture and could lead to partial conclusions. They are nevertheless not only informative (and incredibly so most often) but also useful, as long as the reality of the situation is not forgotten, and one could build upon them to include the various broad types of fighting opposition.

Furthermore, most of the time, the maps available in open source – however impressive the amount of details found on them, which is furthermore regularly updated (as the Wikipedia map shown here which describes the situation in Syria as of 23 March 2013) – only communicate part of the picture and could lead to partial conclusions. They are nevertheless not only informative (and incredibly so most often) but also useful, as long as the reality of the situation is not forgotten, and one could build upon them to include the various broad types of fighting opposition.

2- Following Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi in his “Jihad in Syria,” and Phillip Smith, a central idea should be kept in mind regarding the Syrian civil war – and generally most civil wars: the situation is fluid, changing and much more complex to describe than any categorization could allow.

The Syrian battlefield involves more than 1000 factions and groups (Smith), some more powerful than others. It would seem we are at this stage when the length of the war has created enough havoc and chaos to allow every willing clan to create its own localised guerrilla group (Lund, 2013: 10), whilst the dynamics of the Syrian insurgency has not – or not yet or not completely – allowed a few groups to take real pre-eminence. Thus, all classifications should be taken with the utmost carefulness and what is true one day may well change the next. Alliances and participation in one group or another must also be considered as temporary. Those warring dynamics, yet, need to be observed and understood, because it is finally on the battleground that the destiny of Syria is being played out, while the interactions between international actors and this battleground progressively and incrementally impact the region and shape potential futures. (Author: Dr Helene Lavoix – for Red (team) Analysis – posted on 15 April 2013).

Next article click here.

* Interests will vary according to actors, each trying to influence the overall situation to achieve its goals at best.

Featured image: Free Syrian Army soldier walking among rubble in Aleppo during the Syrian civil war. 6 October 2012. By Voice of America News: Scott Bobb reports from Aleppo, Syria [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

——

Detailed bibliography and list of primary sources forthcoming