(Art direction and design: Jean-Dominique Lavoix-Carli

Photos credits : Didier Descouens & Egor Kamelev)

The uranium requirements created by the planned American nuclear renaissance are immense and unprecedented (see Helene Lavoix, “Uranium for the U.S. Nuclear Renaissance: Meeting Unprecedented Requirements (1)“, The Red Team Analysis Society, 27 November 2024). Yet, the production of uranium in the U.S., the American reserves and resources of uranium, as well as the involvement of American companies in uranium mining are all insufficient to allow the U.S. to meet its future needs in uranium (Ibid.).

The U.S. will thus need to increase its uranium supply overseas, probably through foreign companies. Hence, we need to look at the global uranium supply and demand situation. We need to do so while also accounting for the impact on global uranium supply of the potential new American uranium requirements.

- Trump Geopolitics (2) – The US vs China Geoeconomic War

- AI at War (4): The US-China Drone and Robot Race

- How to use AI for Weak Signals – Trump, the International Revolutionary?

- 2d session of the Fifth Year of Advanced Training in Early Warning Systems & Indicators – ESFSI of Tunisia

- DeepSeek vs Stargate – China’s Offensive on U.S. AI Dominance?

- Trump Geopolitics – 1: Trump as the AI Power President

- Uranium for the U.S. Nuclear Renaissance – 2: Towards a global geopolitical race

Thus, first, we focus on the making of a global gap between supply and demand, stemming, notably, not only from U.S. uranium requirements but also from Chinese ones. Then, we highlight the major consequences of the global uranium supply demand gap, namely rising uranium prices, the necessity to bring about new mines and mills and a tough geopolitical competition for uranium. From there, finally, we identify future possible ways for the U.S. to meet its uranium requirements. We notably envision some changes of the norms of the international order, as already stressed by U.S. President Trump.

Nota: In this article, by resources [in uranium] we mean measured and indicated resources, i.e. those best assessed with the highest degree of “geological confidence” (see glossary).

The U.S. and China: The making of a global gap between supply and demand

The U.S. is not alone in its need for uranium. We must notably see the American requirements in the light of the Chinese nuclear surge (see, “The Future of Uranium Demand – China’s Surge“). This is all the more important that the Chinese nuclear rise has started, whilst the American Renaissance remains an objective. In other words, China is already constructing new nuclear reactors and has already existing concrete plans for more nuclear plants. Hence its uranium requirements are firmer than those of the U.S.. Furthermore, China’s actions to supply its future uranium requirements have also already started. As a result, the options available to the U.S., and to other actors in terms of uranium supply, narrow down.

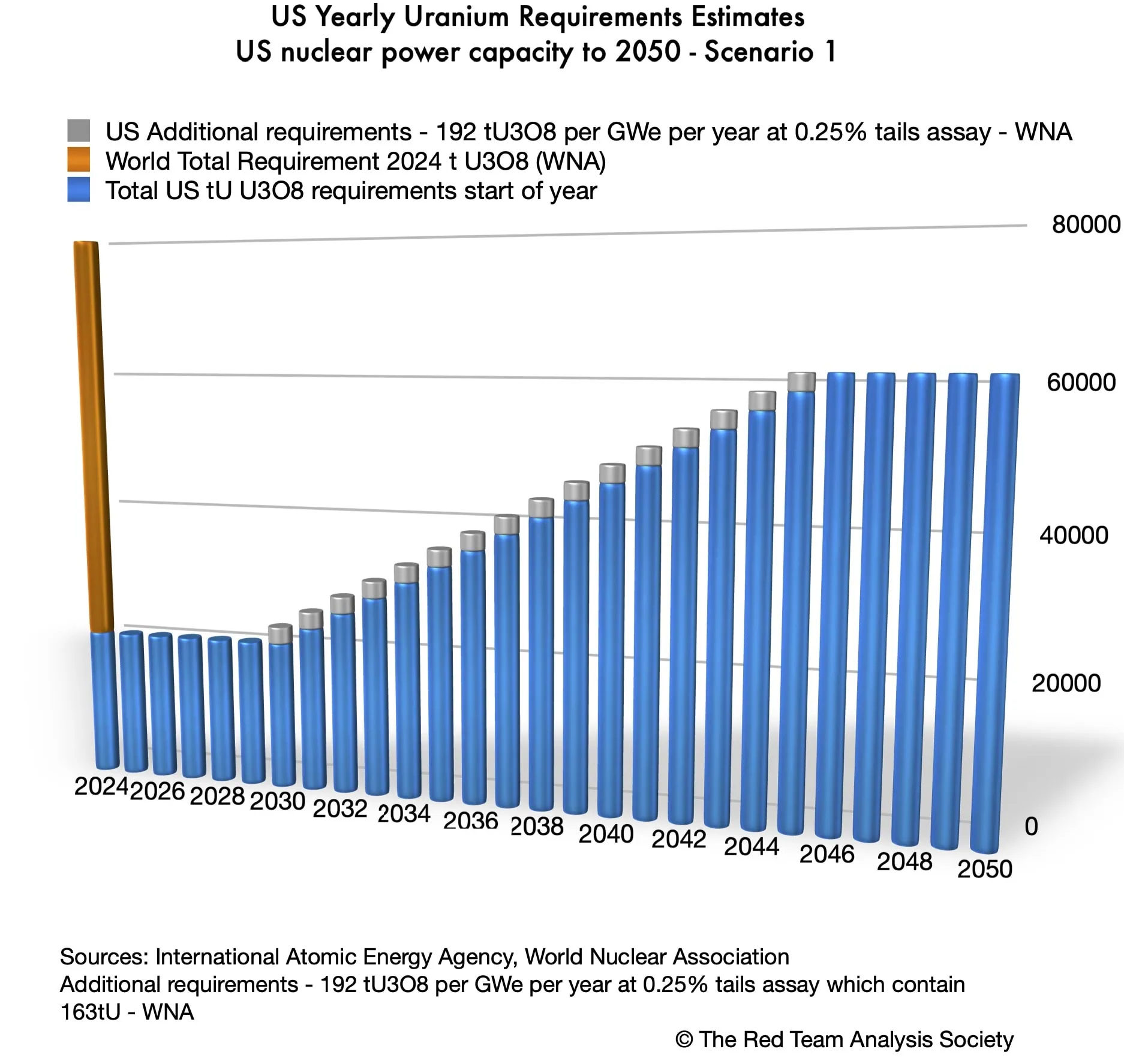

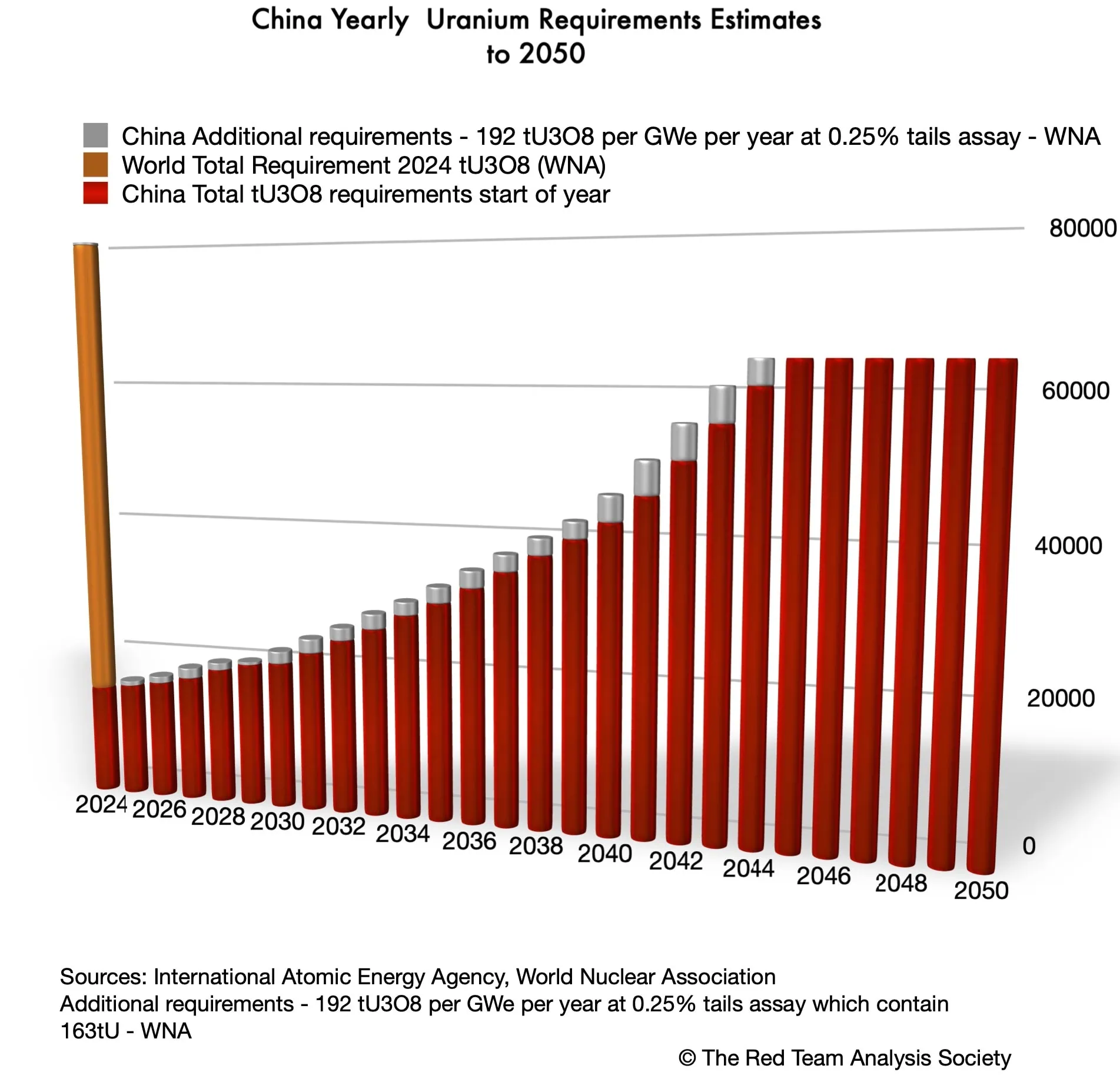

The American and Chinese requirements could look as shown on the two charts below.

If the U.S. uranium requirements alone appeared as immense, the Chinese ones are no less so (“Uranium for the U.S. Nuclear Renaissance: Meeting Unprecedented Requirements (1)“; “The Future of Uranium Demand – China’s Surge“). Indeed they are almost identical. Thus, once we add the U.S. requirements to the Chinese ones, the amount of uranium required is staggering.

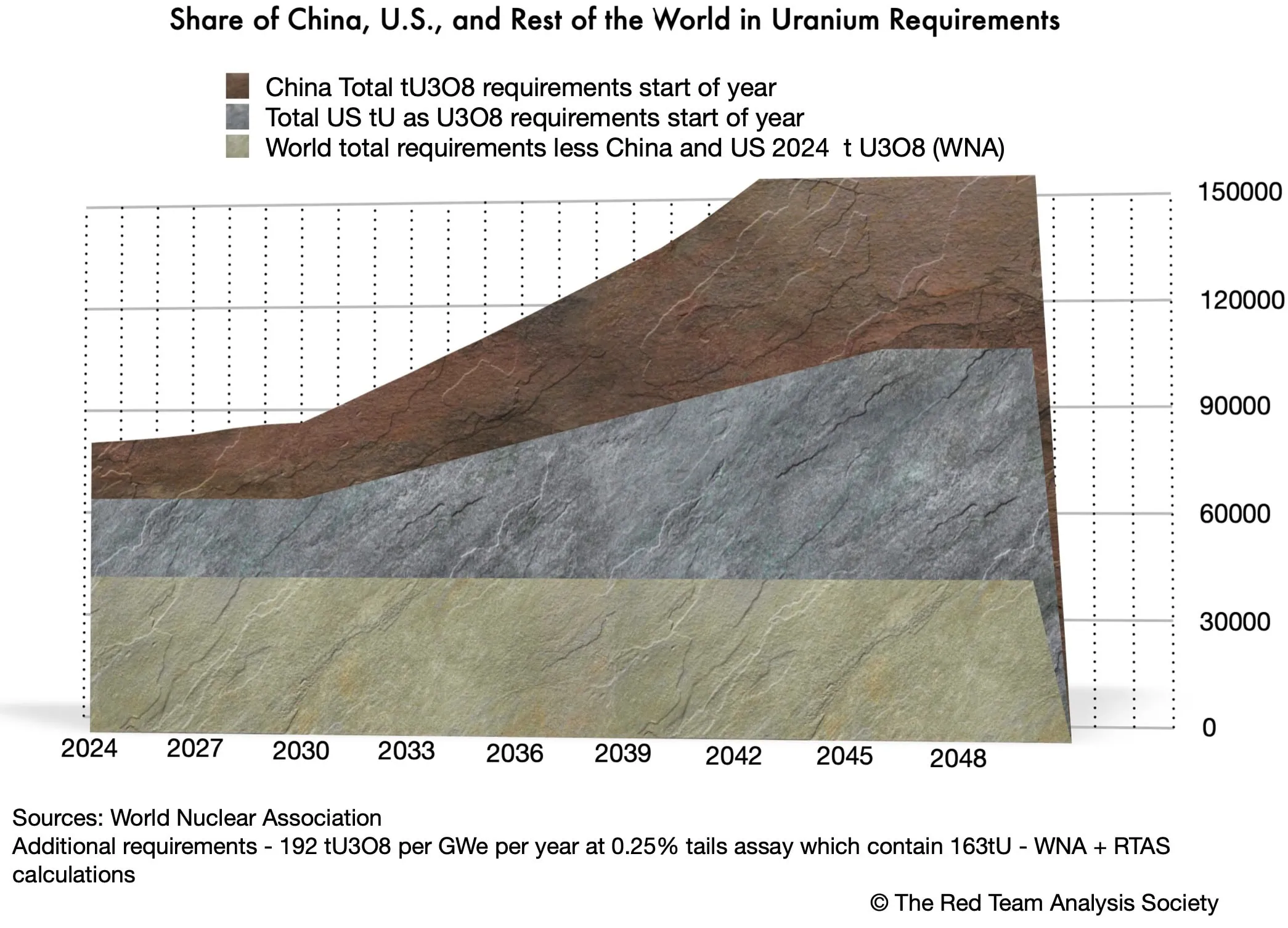

By 2044, American and Chinese yearly requirements will represent each approximately 80 % of 2024 global needs. For these two countries only, this amounts to almost 128.000 tU as U3O8, i.e. 1.6 times the 2024 requirements for the whole world.

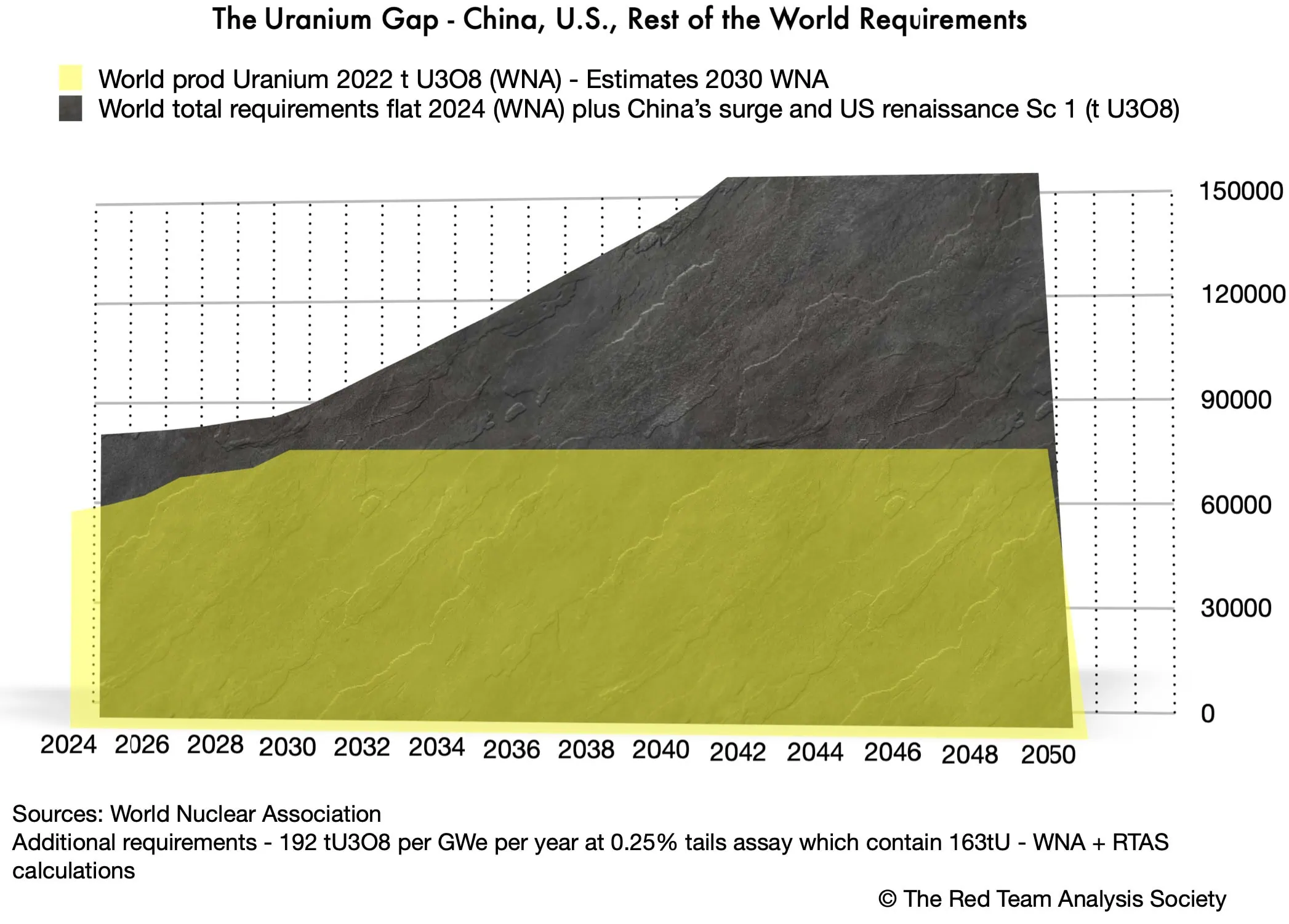

If we look now at uranium production (and not requirements), the World Nuclear Association estimates it reached 58,201 tU as U3O8 in 2022 (“World Uranium Mining Production“, 16 May 2024).

When we compare the Chinese and American uranium requirements plus the estimated amount required by the rest of the world – assuming for now this latter will not increase – with current production estimates, we obtain the following charts. The first one highlights in stone grey a rising global gap between the supply and demand of uranium, and the second the shares of the U.S. renaissance and of the Chinese surge in this rising gap.

As in reality requirements for other countries will also very likely increase considering the global return of nuclear energy, and the willingness to treble nuclear energy worldwide, the gap between supply and demand is likely to be far worse than what is assessed here (Helene Lavoix, “The Return of Nuclear Energy“, The Red Team Analysis Society, 26 March 2024).

Global consequences of the uranium demand and supply rising gap

This rising global gap between supply and demand of uranium will have global impacts, which will then have consequences on each country according to its situation and actions in terms of nuclear energy and uranium supply. Those impacted will also be the U.S. and China.

The rising uranium global gap has three major consequences.

Rising uranium prices

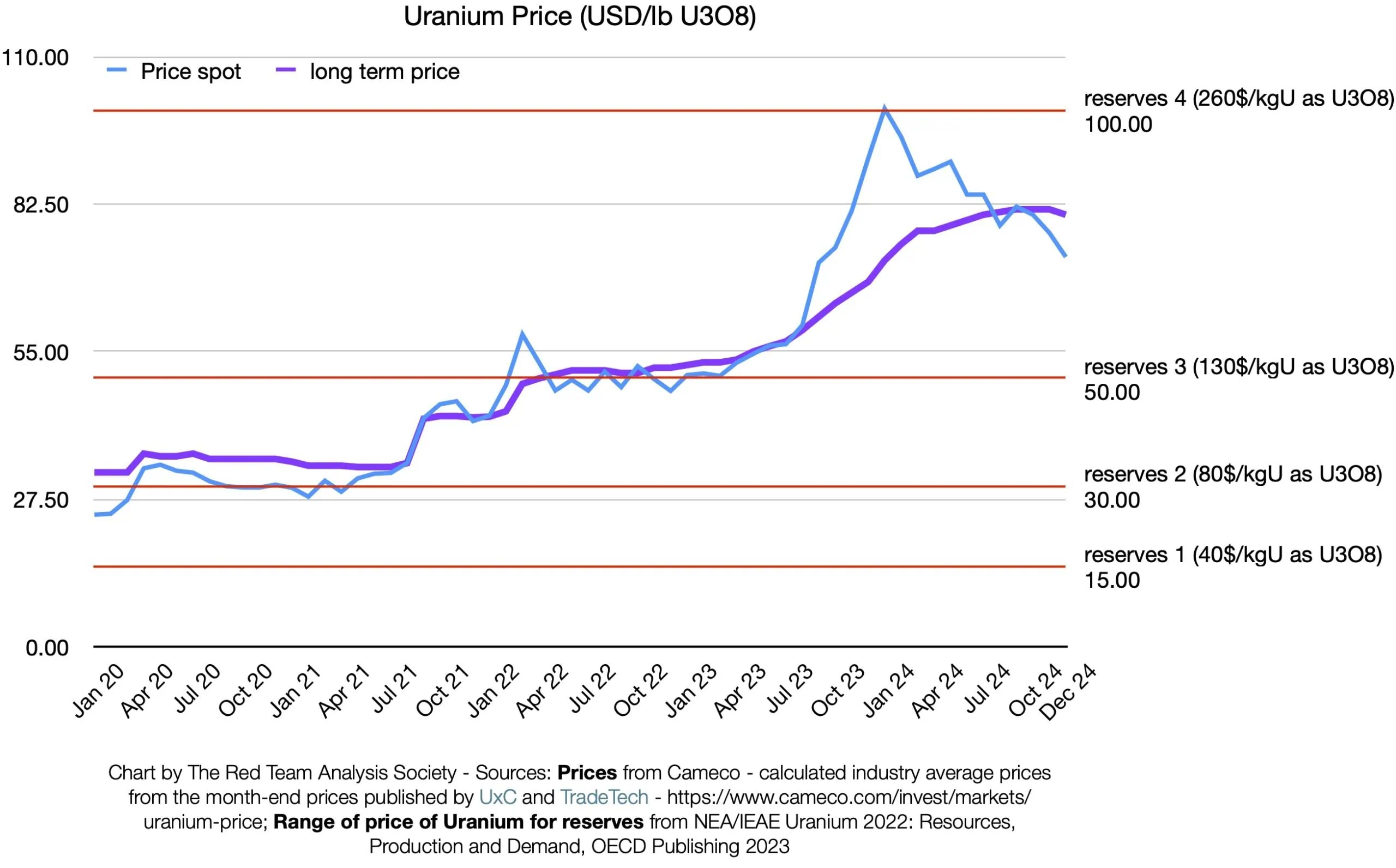

Uranium prices will further increase, which will make new mines viable economically and allow for new production.

The slight decrease shown at the end of 2024 could result from a host of factors, from a divided EU regarding nuclear energy policy to a generalised temporary lack of awareness of the global supply demand gap, through wait-and-see behaviour considering the January 2025 change of Presidency in the U.S., from Biden to Trump (e.g. Kate Abnett, “New EU renewable energy target faces nuclear roadblock“, Reuters, 16 December 2024).

As shown on the chart above, the NEA/IAEA Uranium 2022: Resources, Production and Demand (aka Red Book) uses various price ranges to evaluate reserves and resources in uranium (OECD Publishing, April 2023). The higher the price, the more reserves and resources of uranium available. We are steadily approaching the latest and highest price for the NEA/IAEA estimates of reserves and resources.

As the gap between supply and demand increases, prices will continue rising.

New mines and mills are imperative

New mines must be put into production and mills constructed, and this on a large scale considering future massive requirements notably from the U.S. and China. The mines with the largest reserves and resources will be sought first.

If mines and mills are not constructed on a large scale, then it is the entire “return of nuclear energy” that is endangered. Indeed, the security of uranium supply would then not be ensured, with consequences in terms of energy supply for countries relying on nuclear energy. As a result, the scenario Net Zero by 2050 for greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions would likely not be achieved, with negative feedback loops taking place (IEA, Net Zero by 2050 – A Roadmap for the Global Energy Sector, May 2021).

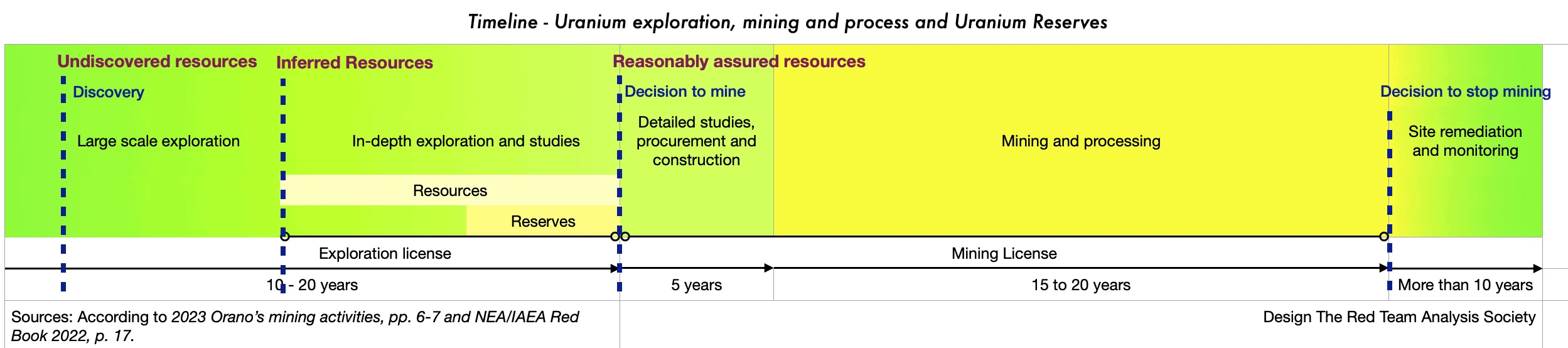

Considering the long timeline to bring a mine to production and the needed amount of financing, the uncertainty surrounding the American renaissance is rather bad news (for the uncertainty, see Towards a U.S. Nuclear Renaissance?).

Indeed, if current mines waiting to be financed – and this is even worse for exploration projects – only find backers once those are almost certain of future requirements, i.e. at best, once a reactor has started being constructed and at worst once the timeline to completion of the reactor seems to be close to two years, then mining investment will likely come too late by three years in the worst case. To be too late by three years means that it will be impossible to start operating the new reactors as fuel will not be available. Nuclear plans will be delayed by at least those three years.

Even in the best case, risks remain. Mining investments will be done first by China and those countries that are considering the security of supply first and that benefit from state-led planning. In other words, when American and Western financiers will be ready to invest in mines because the construction of American reactors will have started, then they are likely to find out that the best mines with the largest reserves have already found financing and that their future production is already sold to others. If part of the production is still available for purchase, then, as ownership of the mining company will be in other hands, the security of supply for those future contracts becomes more fragile.

We can reason similarly for purchases of uranium through long-term contracts not involving investments in mining companies.

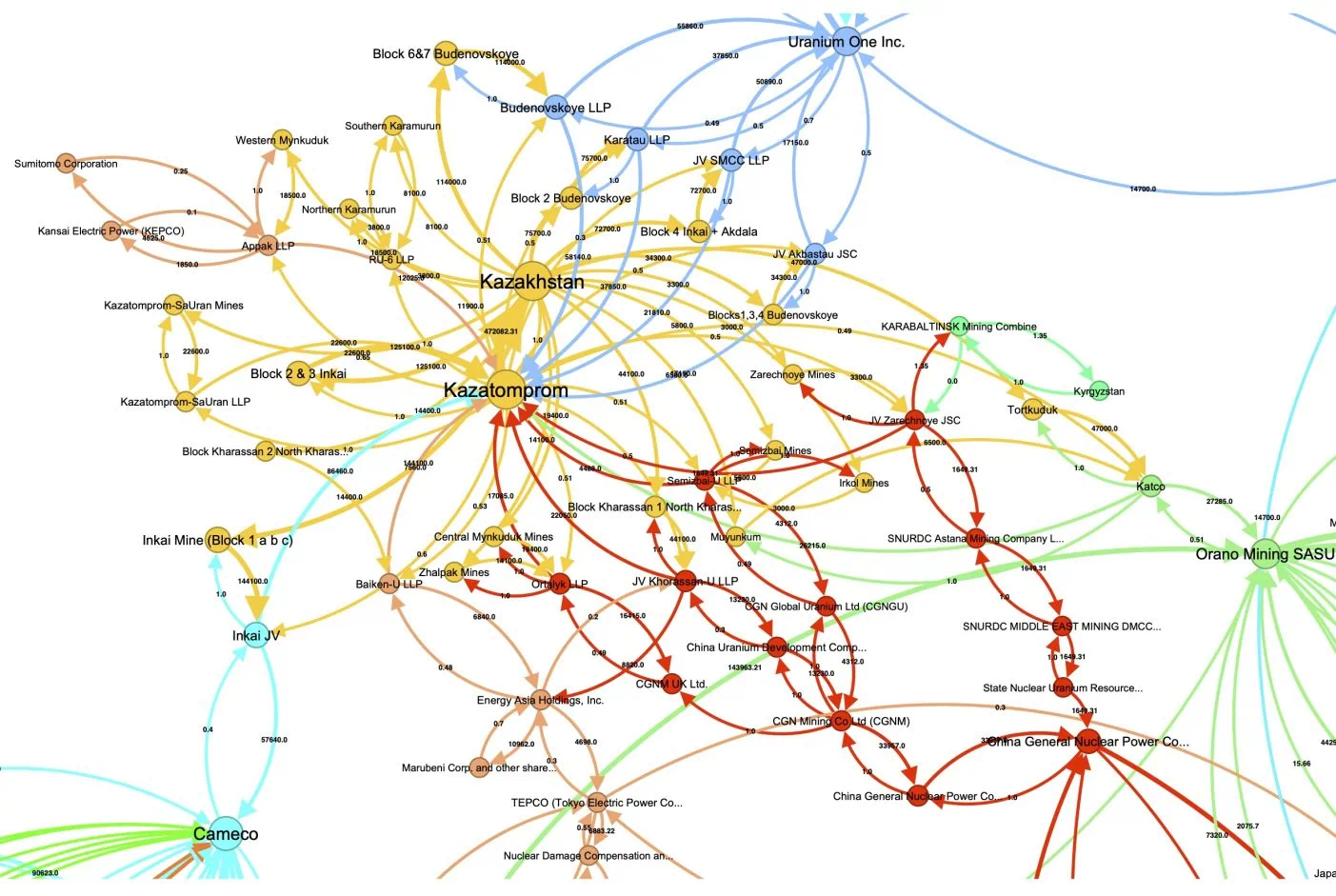

For example, on 15 October 2024, Kazatomprom (the national company of Kazakhstan, responsible for everything related to the nuclear industry) announced a 15 November extraordinary general assembly to vote on an agreement with CNNC Overseas Limited and China National Uranium Corporation Limited on the sale to the latter “of natural uranium concentrates in the form of U3O8 on market terms”. The assembly voted in favour of the agreement at 88.32% (15 Nov 2024 extraordinary general assembly).

The quantity of uranium for the agreement is not mentioned, but we may roughly estimate the overall Chinese purchases of Kazakh uranium, including this new agreement, to be at least between 11.800 and 14.977 tU as U3O8.(1) As the total Kazakh estimated production for 2024 could reach between 22.500 and 23.500 tU as U3O8, then the share already secured by China represents between 50% and 66.5% of the production in Kazakhstan, the first uranium producer in the world and the third most important country in terms of reserves (Kazatomprom 3Q24 Operations and Trading Update, 1 November 2024; chart “Revisiting Uranium Reserves and Resources : reserves, RAR and M&I resources” in Helene Lavoix, “Revisiting Uranium Supply Security (1)“, The Red team Analysis Society, 21 May 2024). If we look at the Kazakh production belonging to the country, which should reach between 15.500 and 16.500 tU as U3O8, it is between 71.5 % and 96.6% that could be bought by China.

China is thus already purchasing a very large amount of the uranium produced in Kazhakstan and an even larger amount of the Kazakh shares in this uranium. Hence, if future Chinese needs are to be satisfied, then new mines will imperatively have to be put into production. Indeed, Kazakhstan and Kazatomprom have an active policy of exploration and development of new mines (e.g. Kazatomprom News, “Kazatomprom obtains the right for uranium exploration at a new site of the Budenovskoye deposit“, 10 September 2024).

Now, we know that part of the Chinese purchases are spot and part are on the longer term (see fn 1). If the Chinese purchases, notably the long-term contracts, are on the “very” long term, for example ten years, then a probably large share of the 11.800 to 14.977 tU as U3O8 of Kazakh production cannot be anymore purchased by anyone else for those ten years. Thus, with the agreement accepted during the 15 November 2024 extraordinary general assembly, China would have secured enough uranium for approximately 78 GWe per year, whilst other countries, including the U.S., wouldn’t.

As a result, once ready to supply its new reactors, the U.S. will have to find other sources of uranium, assuming they are still available. Furthermore, as prices will go up, then the purchases the U.S. will be able to make will be more onerous.

As the whole world is de facto deprived of the Kazakh production bought by China, then it is not only the U.S. that needs to find other sources of uranium but the rest of the world too.

As long as a gap between supply and demand remains, each purchase of uranium and each investment in a uranium mining company and corresponding long-term supply contract rarefies the quantity of uranium that remains available to others. Hence competition for what is left will intensify.

Tough geopolitical competition for uranium

As a result, geopolitical competition to secure uranium supply will be tough.

Indeed, as stakes are high and as countries cannot afford not to have fuel available for their nuclear reactors, we can expect pitiless behaviour to obtain uranium (for stakes, Helene Lavoix, “Revisiting Uranium Supply Security (1)“, The Red Team Analysis Society, 21 May 2024).

The tension will be reinforced by belated financial decisions, besides an absence of awareness of the issue and a related lack of anticipation (see Uranium and the Renewal of Nuclear Energy).

The excellent relations and strategic partnership existing between Russia and China plays to their advantage.

For example, on 17 December 2024, Kazatomprom announced changes of partnership in some of its joint ventures. Russia sold the whole of its shares (49.979%) in JV Zarechnoye JSC to China and is expected to sell 30% participation interest in the capital of JV Khorasan-U LLP (mining) and 30% participation interest in the capital of Kyzylkum LLP (uranium processing facilities) also to China (Kazatomprom News, “Kazatomprom announces the change of the partners in some JVs“, 17 December 2024).

As a result, the new shares of Kazakh reserves and measured and indicated resources in uranium, as well as the related web of stakes looks as on the graph on the right hand side.

In terms of reserves and resources, Russia thus has ceded to China 1.649 tU as U3O8 for JV Zarechnoye JSC (end of life of mine 2028) and 13.230 tU as U3O8 for JV Khorasan-U LLP (end of life of mine 2038).

Those who will be too late in waking up to the new geopolitical competition for uranium may well start buying candles and think about forced de-growth. Alternatively, wars and special operations aiming at securing uranium may become necessary.

Ways forward for the U.S.

Against this highly volatile and challenging backdrop, what are the options opened to the U.S.? The question is of interest not only to the U.S. but also to all other players in the nuclear energy field, considering the global quality of the sector and the weight of the U.S. requirements, should the country manage to go ahead with its plans for nuclear energy.

Relying solely on the invisible hand of the market?

As seen, in 2023, in the U.S., only 4,65% of the uranium delivered originated from the U.S., i.e. came from American deposits, whilst 95,35% came for foreign countries (see Uranium for the U.S. Nuclear Renaissance…). Only 3.88% of the uranium delivered to the United States was purchased by American suppliers, whilst 96.12% was purchased by foreign suppliers (Ibid.).

For the future, the U.S. could thus hope to rely on a similar system, imagining that, as its uranium requirements increase, the market will “automatically” adjust and supply the quantity of uranium needed.

However, this assumes that the private sector from “allies and partners”, to use the U.S. Department of Energy words, will accept to take the risks linked to the supply of uranium, for example those related to delays in terms of nuclear reactors’ construction and corresponding skyrocketing costs (2024 Pathways to Commercial Liftoff: Advanced Nuclear, p.57; for the risks, see “Towards a U.S. Nuclear Renaissance?“). To offset or to the least mitigate those risks, it is likely that companies will tend to be too late in their mining investments rather than too early.

Furthermore, companies will also have to serve all their clients, not only the U.S.. They may thus very well decide to split supplementary production between clients, leaving the U.S. short on its uranium needs. As those companies are not, for the most part, American companies, the U.S. may have little means to pressure those companies for priority supply, in market conditions.

Finally, some of the companies supplying the U.S. are state companies, such as Orano. What does that imply?

Let us go back to the assumption made in the previous article, according to which the increase in production planned by Cameco and French public company Orano for their plants of Cigar Lake(2) and McArthur River/Key Lake(3) is meant to cover the American uranium requirements consequent to the loss of the Russian and Nigerien uranium supply. Previously we imagined that Cameco and Orano would sold all the supplementary uranium produced to the U.S..

Yet, other hypotheses are possible.

If the EU were following the U.S. and sanctioning Russian uranium, or if ever Russia were to decide to ban uranium exports to Europe, then European states would have to find elsewhere corresponding uranium requirements, as well as new ones (EU Parlement, Parliamentary question – E-001721/2024 and answer; Gabriel Gavin and Victor Jack, “EU eyes new clampdown on Russian nuclear sector“, Politico, 5 November 2024). This would be added to the loss of Niger’s uranium (Niger: a New Severe Threat for the Future of France’s Nuclear Energy?). France notably, with its very high stake in nuclear electricity, would be challenged to find a much needed uranium (Revisiting Uranium Supply Security – 1). True enough, Orano progresses in finding new uranium supply sources, for example in Mongolia (e.g. “Mongolia and Orano sign pact for first ever ‘Mongolia-France’ uranium project, International Mining“, 28 Dec 2024). Yet, for that project, production will start in 2028, and peak in 2044 at 2.600 t, 10% of the production being reserved for Mongolia (Ibid.). Compared with the loss of Niger (i.e. France’s share which amounts to 1.268 tU per year), at peak, Orano will thus see its production increase by 1.072 t. It will nonetheless have to find uranium until 2028 to honour its contracts and for France needs. Assuming French uranium stocks are not used, France could be forced to keep any increase in uranium production for its own needs until the Mongolian production starts (Revisiting Uranium Supply Security – 1).

Furthermore, tension between France and Azerbaijan, a key country of the Trans-Caspian International Transport route also known as the Middle Corridor, could also complicate French uranium supply from Central and Eastern Asia (Dauren Moldakhmetov, “What Does the Future Hold for the Middle Corridor?“, The Times of Central Asia, 31 July 2024; among others, R.D. avec AFP, “Tensions France-Azerbaïdjan : la charge d’Ilham Aliev contre le “régime Macron en Outre-mer“, L’Express, 13 November 2024). Assuming this is possible, considering notably the remaining part of the uranium fuel cycle – conversion and enrichment – we may imagine French Orano could have to route Central and Eastern Asian uranium to its Asian clients, rather than using the very long maritime route through a Chinese port, the strait of Malacca and the cap of Good Hope, if the Houthis continue to endanger the Suez Canal route, to bring Asian uranium to Europe.(4) In that case, it could decide to use Canadian uranium for France’s needs, as well as for its non-Asian and European clients. Swaps and barter between companies can also be imagined.

As a result of these potential challenges, as French Orano holds shares in the two Canadian mills of Cigar Lake and McArthur River/Key Lake, assuming contracts allow it, France could decide to keep its part of the increase, i.e. 740 tU as U3O8. In that case, the U.S. would have to find elsewhere 740 tU as U3O8 on a yearly basis.

What we see here emerging with this example – even if it is hypothetical – is that geopolitical decisions (sanctions) and tensions have impact on uranium supply and that stakes in uranium supply may in turn impact decisions regarding uranium that will in turn have geopolitical consequences.

Furthermore, this example also shows that decisions cannot be taken at a macro level but must consider the situation of each country and of each mine and mill.

If we consider the three points above – the risk of uranium supply born mainly by private companies, the imperative, for overseas private companies, to serve all clients, and the uncertainty stemming from using foreign states companies when those states have stakes in nuclear energy – we find that it may prove insecure for the U.S., and actually for all countries, to rely primarily or solely on companies, and worse still on foreign companies, for their uranium supply.

The U.S. DOE’s idea according to which “Mining/milling of uranium will need to be increased from the US, allies, and partners to ensure a secure supply” may very well become impossible, considering geopolitical tension, the uranium supply -demand gap to which the U.S. largely contributes besides China and the needs of these allies and partners (Ibid. p.57).

Actually, the more the global race for uranium intensifies, the less relying exclusively on the invisible hand of the market will ensure a secure supply.

Emulating China’s three pronged uranium policy

The disinterest in terms of production and purchase of uranium by U.S. companies is not only a disadvantage considering the U.S. nuclear renaissance’s objectives, but also a security liability, considering the various stakes of this renaissance, if remedies are not designed (see Towards a U.S. Nuclear Renaissance?).

The Chinese uranium supply policy to rely for one-third on domestic production, for one-third on overseas production through equity and joint ventures and for one-third on purchases cannot be applied as such and at once to the U.S. considering the size of the American resources and reserves and the disinterest of American companies in overseas uranium mining (for the Chinese policy, WNA, “China’s Nuclear Fuel Cycle“, 25 April 2024). It could however be progressively emulated with as objective for 2050 to increase production domestically as much as possible, and for the remaining part of the requirements to rely on purchases for half of the needs and on overseas production though equity and joint ventures for the other half.

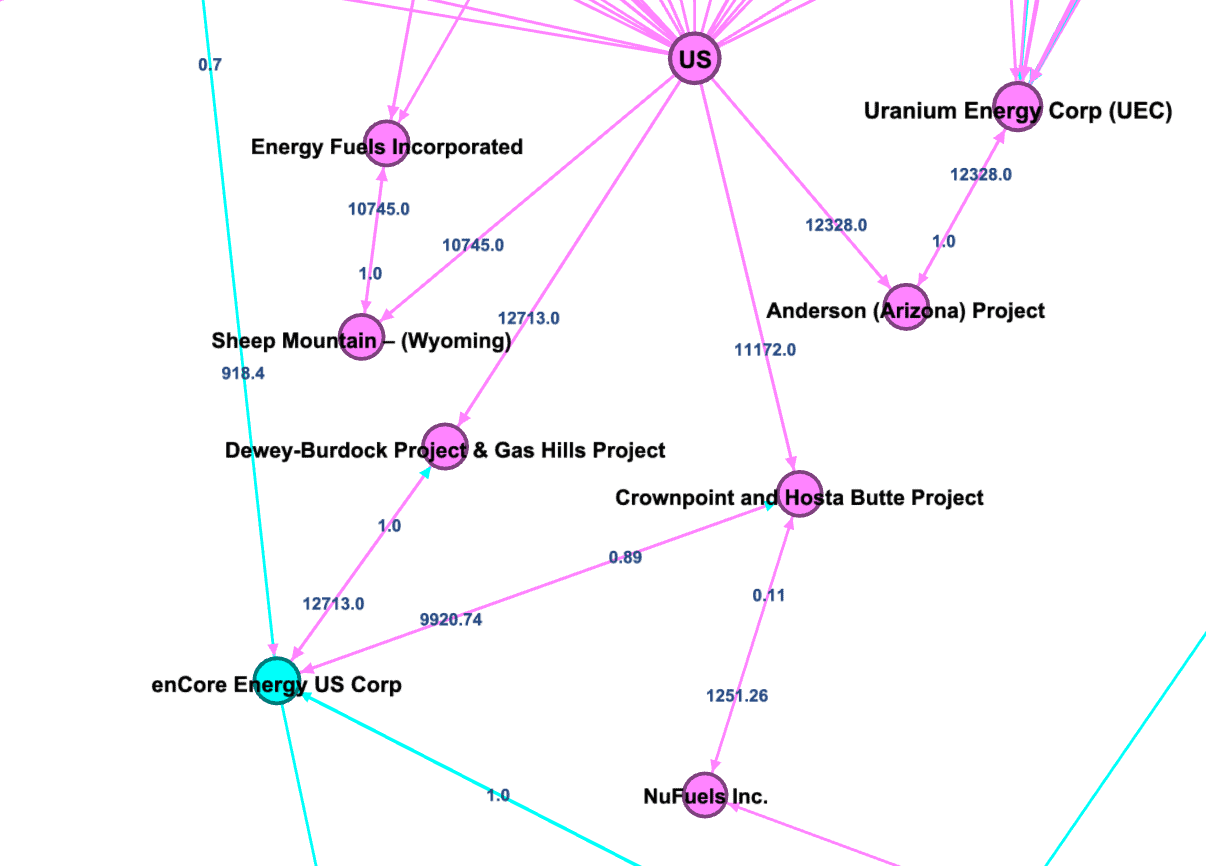

Even though reserves and resources are smaller in the U.S. than in many other countries, they reach nonetheless 147.820 tU as U3O8, when adding all the assessed mines and deposits (see The World of Uranium – 1: Mines, States and Companies – Database and Interactive Graph; “Uranium for the U.S. Nuclear Renaissance…“). Assuming the mines and deposits are truly economically viable, and can be developed considering environmental constraints and indigenous peoples’ rights, the American mines with the largest reserves and resources could be chosen for priority development and thus financing.

For example, the following deposits could be selected: the Anderson project in Arizona belonging to U.S. Uranium Energy Corp (UEC), Sheep Mountain in Wyoming belonging to U.S. Energy Fuels Inc., the Dewey-Burdock Project & Gas Hills Project of Canadian held enCore Energy US Corp and the Crownpoint and Hosta Butte Project belonging to the same company and to Nufuels Inc. (identified through The World of Uranium – 2)

Then, U.S. mining companies, which are solid enough financially to do so, could attempt to take hold or create joint ventures with current holders of large foreign deposits close by, i.e. in Canadian Saskatchewan. Alternatively, concerned actors such as U.S. specialised funds could finance mines in a way that would include an agreement to preempt production for U.S. purchase.

The Rook 1 Project of NexGen Energy Ltd with its 98.738 tU as U3O8 reserves and resources is an obvious candidate. According to NexGen Energy Ltd plans, the mine would produce approximately 11.232 tU as U3O8 per year (29.2 Mlbs U3O8 per year for the first 5 years, with possible expansion from year 6 to end of mine life (11.7 years) – NexGen Investors presentation December 2024). For 4.5 years, the U.S. would have enough uranium for its supplementary requirements. However, after that time, it would again have to find new mines. It would also have to make sure that production of the Rook 1 project does not decrease after the initial 5 years.

If we consider the option to invest as much as possible in mining companies in Saskatchewan, how much of the uranium of Saskatchewan could be needed for the American nuclear renaissance?

The current estimates for the main reserves and resources known for Canadian Saskatchewan (Ca) amount to 555.258 tU as U3O8 (The World Of Uranium-1 and 2). If we remove the two largest mines already exploited, Cigar Lake and McArthur, the remaining amount of reserves and resources amounts to 315.584 tU as U3O8 (The World Of Uranium – 2). We saw the U.S. requirements for scenario 1 of the nuclear renaissance corresponded to an increase of 2.496 tU as U3O8 per year in terms of supply, starting in 2029-2030, to reach from 2045-2046 61.324 tU as U3O8 of yearly requirements. Thus, if we assume that all reserves and resources of Saskatchewan are used exclusively for U.S. requirement needs, then during the year 2045, all the known uranium in the Canadian province will have been used.

This hypothesis is unlikely considering that the main companies operating in Saskatchewan are Cameco, a private global Canadian company with clients worldwide, and French Orano also with clients worldwide and the need to serve in priority France with its high stake in nuclear energy.

Thus U.S. companies will not only have to invest as much possible in Saskatchewan, considering other states’s needs, but also in other Canadian provinces such as the Nunavut and Labrador and fundamentally everywhere in the world where uranium can be mined.

Furthermore, an intense exploration policy for uranium mining will need to be carried out as soon as possible considering high uncertainty and long timeline, as shown by the hypothesis of an exclusive American use of all Saskatchewan reserves and resources. Without exploration, if the U.S. nuclear renaissance takes off, it will be impossible to meet the requirement needs of the U.S. and of other countries by the end of the period.

This could also mean an even more intense geopolitical competition.

Ensuring territories endowed with uranium supply the U.S. first?

Considering the stakes, and faced with the imperative of uranium supply security, in a highly competitive geopolitical environment, the U.S. may choose to annex, one way or another, territories endowed with uranium resources, besides other critical minerals and other strategic assets.

We find here a logic to U.S. president-elect Trump’s declarations regarding his desire to make Canada an American State and to buy Greenland, which uranium potential is “considered [as] relatively high”, according to the 2018 Official Geological Survey Uranium potential in Greenland (e.g. Jessica Murphy, “Trudeau says ‘not a snowball’s chance in hell’ Canada will join US“, BBC, 7 December 2025; Maia Davies, “Greenland ready to work with US on defence, says PM“, BBC, 13 January 2025). The Republicans’ attempt to introduce a bill in the House of Representatives (the “Make Greenland Great Again Act”), which would allow the U.S. to buy Greenland, underlines the reality and seriousness of President Trump’s proposal (Magnus Lund Nielsen, “Make Greenland Great Again Act seeks support in US“, Euractiv, 14 January 2025).

The U.S. would thus start a whole new period for international politics, one where the principles built from the Montevideo Convention on Rights and Duties of States (1933), and then enshrined in the United Nations charter, signed on 26 June 1945, in San Francisco, have become outdated. We would be back to a time where conquest and war become fully part again of international relations.

If ever the U.S. were really annexing Greenland or any other territory, then the security of its uranium supply would be greatly enhanced for the amount of uranium held by the territory annexed. However, here, this uranium would not anymore be available to others. As China will also have secured, in a different way the uranium it needs, the remaining uranium would have shrank drastically. This is not anymore a couple of mines or part of a production that would be removed from the market, but a whole territory endowed with many mines and deposits. According to their stakes in nuclear energy, and to their power, other states would then have to compete for what is left. The likelihood to see force being used is greatly heightened.

Even if war does not ensue from Trump’s declaration and if the “Greenland Act” is not voted, current reactions from Greenland and Denmark to the threats nonetheless seek to appease the U.S. by giving it more than it had before, while also stressing the sovereignty of Greenland (e.g. Davies, “Greenland ready to work with US on defence, says PM“, BBC, 13 January 2025). As a result, by making concessions, Greenland and Denmark tend to condone the change of principles.

Thus, geopolitical race and tensions for uranium supply security could very well be not only an instance of forthcoming wars for resources, but also participate in signalling and spearheading a very change of the international order.

Notes

(1) Estimating roughly the amount in t U as U3O8 of the agreement between Kazatomprom and CNNC Overseas Limited and China National Uranium Corporation: We know that “The transaction value, cumulative with the previously concluded transactions with CNUC [long-term contract] and CNNC Overseas [spot], comprises fifty percent or more of the total book value of the Company’s assets”, hence Kazatomprom extraordinary general assembly. The total asset of Kazatomprom was 3.331.448 million KZT on 30 Sept 2024 (Kazatomprom consolidated statements p.12). Thus, the total amount of sales of uranium concentrate to China, including prior contracts, could be over 1.665.724 million KZT after the EGA on 15 November 2024, i.e. approximately 3.173.32 million USD. We also find sources giving the amount of $2.5 billion USD (e.g. Olga Tonkonog, “Kazakhstan to finalize major uranium deal with China“, Kursiv, 15 October 2024; Vagit Ismailov, “Chinese Companies to Purchase Uranium Concentrates from Kazatomprom for $2.5 Billion“, The Times of Central Asia, 18 Nov 2024).

If we assume an agreement using September 2024’s long term uranium price, i.e. USD 81,50/lbs U3O8 (Cameco), then the minimum quantity purchased as a whole by China to Kazakhstan could be 38,937 Million lbsU3O8, or 14.977 tU as U3O8. The quantity could be larger as previous contracts were certainly contracted at a lower price. If we take the figure of 2.5 billion USD, then the global purchase of uranium concentrate by China could be 11.800 tU as U3O8. These amounts are only very rough estimates, given the number of assumptions made.

The total amount of sales to China was 540.405 million KZT on 30 Sept 2024 (against 342.293 million KZT in Sept 2023 and 522.521 million KZT on 31 Dec 23, Ibid. p.13 and Notes to the Consolidated Financial Statements – 31 December 2023, p. 15). This shows a consequent increase in Chinese purchases has already taken place.

(2) Cigar Lake is owned at 54.547% by Cameco, 40.453% by Orano Canada Inc. (Orano) and 5% by TEPCO Resources Inc.

(3) The Key Lake mill is owned 83.333% by Cameco and 16.667% by Orano.

(4) Estimated transit times

| Shipments from major Chinese ports to North America’s West Coast ports | 15 to 20 days (Artemus) |

| Shipments from Chinese ports to Europe | 30 to 35 days (through the Suez Canal) (Maersk) |

| 39 to 44 days (+ up to 9 days through the Cape of Good Hope) (trans.info) | |

| Transit time through the Middle corridor from China to Europe | 18 to 23 days (with plans for 18 days, then 10 to 15 days) (intellinews) |

| Shipments from Canada’s Atlantic coast to major European ports | 10 to 25 days (OCT) |

Very good https://is.gd/tpjNyL