A warning does not exist if it is not delivered. This is a key lesson highlighted by the famous expert in warning Cynthia Grabo, who worked as an intelligence analyst for the U.S. government from 1942 to 1980 (Anticipating Surprise: Analysis for Strategic Warning, Editor’s Preface). Similarly, a foresight product such as scenarios, for example, has to be delivered or communicated. Actually, Cynthia Grabo’s point is true for any anticipatory activity, whatever its name, from risk management to horizon scanning.

Furthermore, if strategic foresight and early warning are to be actionable, if they are to allow for true preparedness, then clients – the decision-makers and policy-makers to whom the product has been delivered and communicated – must pay heed to the foresight, or to the warning. What decision-makers then decide to do with those warnings is another story.

Thus, from our point of view – i.e. the perspective of those who are in charge of doing early warning and foresight – decision-makers must receive the warning or foresight product, know they have received them and, as much as possible, consider them.

This part of the process of early warning, strategic foresight, futurism or more broadly anticipation, which handles delivery and communication, tends to receive less attention than other dimensions such as analysis or collect of information. Yet, if we want decision-makers to pay heed to our work, if we want societies to move from reaction to anticipation and action, then delivery and communication are as important as analysis and collect.

This article presents fundamentals for the delivery of early warning and strategic foresight products and the origin of this knowledge. It then suggests that if we were adding a user-centric approach to our understanding of delivery and communication, then we could improve this part of the strategic foresight and early warning process.

Lessons learned

The most famous strategic surprise or warning failure is the attack on Pearl Harbour on 7 December 1941. This attack was indeed a surprise that dealt a devastating blow to the American fleet, even though the fleet recovered. It also overcome the reluctance of the U.S. to enter World War II beyond support of allies. War was formally declared against Japan on 8 December, bringing truly America into World War II (e.g. a Bibliography on Pearl Harbour, from the point of view of strategic surprise, Imperial War Museum, “What happened at Pearl Harbour“).

This event may be considered as the starting point for the study of warning. Indeed, Pearl Harbour and other strategic surprises led intelligence officers and analysts to study how surprise could happen, so as to avoid these very warning failures. Roberta Wohlstetter, Pearl Harbor: Warning and Decision (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1962) is considered as the first famous instance of such studies. Cynthia Grabo’s classified A Handbook of Warning Intelligence (three volumes published in 1972 and 1974), which gave the unclassified 2003 Anticipating Surprise: Analysis for Strategic Warning, is another fundamental textbook for understanding and avoiding warning failures.

We can thus use more than fifty to sixty years of knowledge and understanding gathered in the field of indications and warning, that became strategic warning and early warning. Utilising these lessons learned from strategic surprise and warning failure we can highlight key points for delivery and communication of strategic warning and foresight.

- “Clients” or “customers” for our warning or foresight must be identified. We can actually map these clients.

- Warning officers and more broadly early warning and strategic foresight practitioners must learn to know their decision-makers, their “clients”. They must develop, overtime, a trusting relationship with them.

- Warning and foresight products can, as a result, be adapted to customers in terms of:

- format: making sure the format is right for each decision-maker receiving the product

- understanding: making sure each decision-maker can understand the product (I mean really understand it fully, not getting only a superficial vision of it).

- Products must be delivered to customers. Related necessary channels of communication must be created if need be.

- Strategic foresight and especially early warnings must be delivered in a timely fashion (see Hélène Lavoix, “Revisiting Timeliness for Strategic Foresight and Warning and Risk Management“).

- Feedback on delivery and products must be asked from customers, hoping the latter will have time to provide them.

If we pay attention to these steps and follow them, then we have improved the likelihood to see our customers pay heed to foresight and early warning products.

Many challenges, however, are lurking behind those apparently simple steps, potentially hindering the best completion of each of them. Here we shall focus on an approach that could constructively help us in carrying out these steps.

Moving from classical customers to users?

Usually, chains of command and hierarchical structures define who gets early warnings and strategic foresight products, such as scenarios, for example. They have been established over time, exist and are either necessary or inescapable or both. Most of the time, those who receive warnings and foresight analysis are set policy-makers and decision-makers.

Yet, it could be also of interest to move from the idea of existing pre-determined “customers” or “clients” to a slightly different notion, the idea of users.

A user-centric approach would imply, for example, that we provide those receiving the results of our warning or foresight analysis with tools and instruments, be they concrete or immaterial, that are first and foremost useful and of value to them. This could be any device – including in terms of format – that would be helpful to users for moving from the reception of our products to action and the accomplishment of their mission.

With the idea of users, the emphasis is set on a long-term relationship, on the consideration of the other and his or her needs.

If we adopt a user-centric approach, then we can start our process of identification of the recipient of our early warning and strategic foresight analysis again, with a fresh mind:

- Are we sure that all the necessary, actual and potential users have been identified?

- Would other people, potentially not belonging to the usual chain of command or hierarchy benefit from using the early warning or the foresight product?

- Trump Geopolitics – 1: Trump as the AI Power President

- Uranium for the U.S. Nuclear Renaissance – 2: Towards a global geopolitical race

- The New Space Race (1) – The BRICS and Space Mining

- Uranium for the U.S. Nuclear Renaissance – 1: Meeting Unprecedented Requirements

- Fifth Year of Advanced Training in Early Warning Systems & Indicators – ESFSI of Tunisia

- Towards a U.S. Nuclear Renaissance?

For each type of users and even each user, we would then need to follow the steps related to the delivery and communication of warnings identified above. Each user could receive specific warning products tailored to its needs.

This approach would certainly be most useful, for example, in the case of the COVID-19 pandemic for example, as each and every human being is a whole theatre of operation and entire battlefield for the virus and where actions must be taken by each individual very quickly in series of instants. It would deserve further detailed research as we could find more efficient approaches that only considering if a person is positive or not, contact case or not and needs to isolate or not. Again, this would help moving from reaction to anticipation.

However attractive a user-centric approach may appear, it may also be difficult to implement because, for most actors, having foresight, being able to anticipate, also touches upon hierarchy and ultimately upon power. Thus, within an organisation, care will be taken to clear the question first at the highest level of decision-making.

Moving from “product” and “delivery” to “tools” and “reception”

Classically, once all policy-makers and decision-makers are known, then, ideally, the final result of the analysis is formatted to be adapted to policy-makers and decision-makers and delivered. The aim is to get their attention and raise their awareness.

If we move to the user centric approach, we can start thinking about usage of early warning or foresight analysis rather than just products and switch from an emphasis on delivery to reception.

We could ask questions such as:

- In which circumstances and how would users use the warning or foresight analysis?

- What are the best channels of communication for transmitting efficiently and timely the warnings or strategic foresight analysis that will give the best possible reception by the user?

- Which form should the early warning and the foresight analysis have for best usage by each user or type of user?

The questions above are particularly important as they will also lead us to find out how users think, the dynamics behind cognition, the opportune moments for communication, what and who has influence on the users’ thinking. They will demand we consider the various biases that alter the understanding of any human being (e.g. Heuer, Psychology of Intelligence Analysis, 1999). These indeed do not only affect analysts and analysis, as usually considered. They also impact people receiving our foresight and early warnings and, as Woocher points out, the relationship between analysts, officers and to customers. Answering these questions properly thus will help us changing mind-sets a difficult and constant hurdle strategic foresight and early warning must always overcome.

If we keep in mind that useful recipients of early warning and strategic foresight analysis are not only set clients in a hierarchy but also, first and foremost, users, then we can imagine, design and implement an overall strategy centred on the actionable use of early warning and strategic foresight, for best delivery and communication of our analyses.

A short bibliography

Grabo, Cynthia M., and Jan Goldman. Anticipating Surprise: Analysis for Strategic Warning. [Washington, D.C.?]: Center for Strategic Intelligence Research, Joint Military Intelligence College, 2002.

Heuer, Richards J. Jr., Psychology of Intelligence Analysis, Center for the Study of Intelligence, Central Intelligence Agency, 1999. See also access through Homeland Security Digital Library.

Lavoix, Helene, Ensuring a Closer Fit: Insights on making foresight relevant to policymaking. Development 56, 464–469 (2013), https://doi.org/10.1057/dev.2014.27

Meyer, Christoph O., et al. “Recasting the Warning-Response Problem: Persuasion and Preventive Policy.” International Studies Review, vol. 12, no. 4, 2010, pp. 556–578. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/40931357.

Nolan, Janne E., and MacEachin, Douglas, with Kristine Tockman, Discourse, Dissent and Strategic Surprise Formulating U.S. Security Policy in an Age of Uncertainty. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University, Institute for the Study of Diplomacy, 2007.

Wohlstetter, Roberta. Pearl Harbor: Warning and Decision. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1962.

Woocher, Lawrence, “The Effects of Cognitive Biases on Early Warning,” Presented at the International Studies Association Annual Convention (2008).

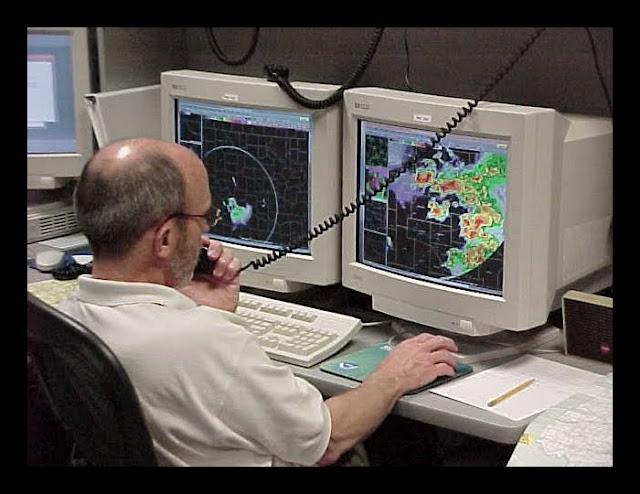

Featured image: by ArtTower, Pixabay, Public Domain.

Hi Lee Robinson,

I am delighted that you liked this post and all the more so that you pasted it in your blog. Would you be kind enough, however, to add the mention: July 13, 2011 by Helene Lavoix before the via Red (team) Analysis, to respect the attribution and copyrights rules as I licenced my work under CC3.0… as mentioned at the bottom of the webpage (which makes me think it is not well located, i shall put it elsewhere)

Thanks!

Helene