This article will be the last one that presents the current state of play and the five categories of actors fighting in and over Syria.

The rise of the two groups of factions presented below – the Syrian Sunni factions intending to install an Islamist state in Syria and the Sunni extremist factions with a global jihadi agenda – as well as their mobilization power has been, first, eased by the protracted quality of the conflict and the despair it implied among Syrian people. It was then facilitated by the initial inability of the moderates to find support in the West, thus to demonstrate their power.

“Nationalist Salafis”: Syrian Sunni factions intending to install an Islamist state in Syria

The first nexus is composed of more extreme Islamist groups – compared with those seen previously – and of “Nationalist Salafis” groups – to use Lund (2013:14) terminology, noting that scholar of Jihad in Syria, Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi questions the very dichotomy between Nationalist Salafis and Jihadi Salafis (see below update 8 July).

Nationalist Salafis want to create an Islamic Sharia state in Syria. Lund (2013: 14) quotes Abdulrahman Alhaj, an expert on Syrian Islamism he interviewed in January 2013:

“When it comes to the salafis, we have to separate between two things. There are publicly declared salafi groups who have an experience of [armed] salafi work outside Syria, and who have a systematic salafi thinking. These groups, the salafiya-jihadiya [salafi-jihadism], are not many, but they affect people’s thinking.”

“The others are young, extremist people. They are Sunni Muslims who just follow this path because there is a lot of violence. Day after day, they come face to face with violence, so they adopt salafism, but they are not really part of the salafiya-jihadiya ideologically. Like Ahrar al-Sham: they are not part of the salafi-jihadi movement. There are of course real salafis among them, but mostly they are just extremist sunnis without a systematic salafi ideology. It’s very different from Jabhat al-Nosra.”

Within those groups one finds two major alliances, who are attempting to unite factions.

The Syria Liberation Front (SLF) also known as the Syrian Islamic Liberation Front (SILF) factions (Jabhat Tahrir Souriya or Jabhat al-Tahrir al-Souriya al-Islamiya) was created in September 2012 when some factions ended their associations with the FSA and dissolved with the creation of the Islamic Front on 22 November 2013. The groups that are mentioned as belonging to the SLF are: two of Syria largest Islamist groups, Kataeb al-Farouq and Suqour al-Sham (Lund 2013: 16), Liwa al-Tawhid and Liwa al-Islam (Lund 3013: 27 using Noah Bonsey, Lund, 3 April 2013). According to Lund, most of the SLF factions are also now part of the Supreme Joint Military Command Council (Ibid: 13), despite their ideological outlook, which also underlines again the pragmatic feature of affiliations and the shifting and lose characteristic of alliances, as suggested previously.

The SILF/SLF would count an estimated 37.000 fighters (Ignatius, 2 Avril 2013; see also Lund’s related comment, 3 April 2013).

The Syrian Islamic Front (SIF) (Al-Jabha al-Islamiya al-Souriya) was created in December 2012 under the leadership of the more powerful Ahrar al-Sham and dissolved with the creation of the Islamic Front on 22 November 2013. It initially included 11 factions, covering most of the territory (see mapping below and previous versions of the mapping accessible below), which were, in January and February 2013, reduced to 7 through the merging of various groups (Lund, 2013: 25-27). Since April 2013, the SIF counts one new member, the Haqq Battalions Gathering (Tajammou Kataeb al-Haqq) (Lund, May 3 2013). Between 10.000 and 30.000 fighters could be part of the SIF (Lund, 2013: 23).

Talks between initial SIF groups and the SLF had taken place when the SLF was created but failed for various reasons, from ideological to disagreements between groups.

To access the actors’ mapping (updated 27/01/2014), become a member of The Red Team Analysis Society. If you are interested in specific actors’ mapping and latest updates,  contact us.

contact us.

If you are already a member, please login (don’t forget to refresh the page). You can access the page through my account, click on view in “My membership table” to access the list of the articles available to members only).

Lund (Ibid: 17-19) qualifies the SIF as an Islamist “Third Way,” strictly salafist but also pragmatic, able to discuss with the West, and to cooperate on the ground with the SMC or with salafi-jihadi groups, while also criticizing the latter, as shows the 4 May 2013 statement by Ahrar al-Sham on “Jabhat al-Nosra’s recent declaration of allegiance to al-Qaida’s Ayman al-Zawahiri.” (Lund, 4 May 2013):

“It seeks to demonstrate a strict salafi identity, and makes no attempt to hide its opposition to secularism and democracy. but it also tries to highlight a streak of pragmatism and moderation, intended to reassure both syrians and foreign policymakers. In this way, it sets itself apart as an Islamist ”third way”, different from both the most radical fringe of the uprising, and from its Western-backed islamist mainstream.” (Lund, 2013: 17)

However, the SIF aims at establishing a Sunni Islamist Theocracy, allowing only some modicum of consultation and political freedom within the bounds of sharia law (Ibid: 19). It has already started working towards this goal when, as described by Lund (Ibid: 25), it develops a “humanitarian and non-military activity.” It does not only fight but also plays the role of a real political authority, which strengthens both its mobilization power and its resource-base. Thus, overthrowing the regime of Bashar al-Assad is only a step towards achieving its objectives, and the “Third Way” may only last temporarily, assuming the SIF continues its current course, and finds access to sufficient and secure resources and fundings (for details on funding see Ibid: 27).

For more details on the SIF and, among others, salafism in Syria, I highly recommend Lund’s report.

Update 31 May 2013

- 26 May 2013 – The SLF would have declared war on The Kurds: “a statement signed by no less than twenty-one armed groups declared ”Kurdish defense units, YPG, are traitors because they are against our Jihad.”The goal, according to the statement, is a “pending the completion of comprehensive cleansing process”, liberation from “PKK and Shabiha”. The statement was published by the “Syrian Islamic Liberation Front” – Syria Report, 27 May 2013 – “Insurgents Declare War on Syrian Kurds“

Update 8 July 2013

Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi in his meticulous analysis of the relationships between JAN and ISIS (see below), for the region of Raqqah (24 June 2013 for Jihadology), following common demonstrations, questions:

“In Raqqah itself, further evidence of an ISIS-JAN unity became clear in the counter-demonstrations on the ground. Here is one such video, featuring several youths holding the banners of Harakat Ahrar ash-Sham al-Islamiya (which, to recall, was the main group of battalions responsible for the rebel takeover of Raqqah in March), ISIS and the general flag of jihad.

… The recent developments should also debunk the false dichotomy posed by some commentators of ‘Salafist nationalist’ Syrian Islamic Front [SIF] groups like Harakat Ahrar ash-Sham al-Islamiya versus transnational jihadist groups (cf. my overview of statements put out by various factions on Sheikh Jowlani’s bayah to Sheikh Aymenn al-Zawahiri).”

Next updates

21 October 2013: Facing the Fog of War in Syria: The Syrian Islamists Play the Regional “Game of Thrones”

27 January 2014: the Rise of the Salafi-Nationalists?

Sunni extremist factions with a global jihadi agenda

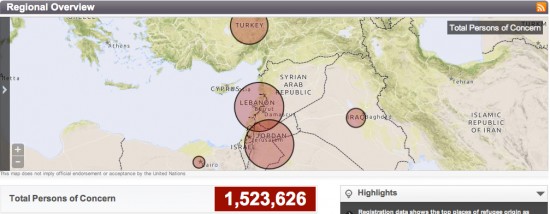

The last nexus is composed of salafi-jihadi groups or salafis groups with a global agenda, such as Al Qaida, and includes many foreign fighters – Tunisian, Libyan, Iraqi, Chechen (e.g. Solovieva, 26 April 2013, AlMonitor; Kavkav center, 26 March 2013) and European. ICSR Insight estimates that “between 140 and 600 Europeans” from fourteen countries, “have gone to Syria since early 2011, representing 7-11 per cent of the foreign fighter total” (April 2013).

The best known group is Jahbat Al-Nosra or Al-Nusra, created in January 2012 and declared a terrorist group by the U.S. in December 2012. It is seen “as the most effective fighting force in Syria” (Bergen and Rowland, 10 April 2013). In November 2012, Washington Post David Ignatius, using sources from the FSA, considered it included “between 6,000 and 10,000 fighters.”

In mid-April, Jabhat al-Nosra, answering to al-Zawahiri and then to Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, leader of Al Qaida in Iraq (ISI, Islamic State of Iraq) and as excellently summarized by Lund (4 May 2013) “promised to follow every order from Zawahiri as long as this does not contravene sharia law,” while refusing merging with ISI (see for full detailed analysis and translated documents, Barber, 14 April 2013). Jabhat al-Nosra thus asserts an Al Qaida in Syria, in a nationalist move that is not without recalling salafi-nationalist groups, and stresses its aim to establish an Islamist state in Syria, “The Islamic State of al-Sham” (ISIS – see below update 8 July). Al-Sham stands for Bilad al-Sham, i.e. The Levant (today’s Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, Palestine, Israel, and potentially the Hatay Province of Turkey). The choice of words could potentially indicate a wish to revise borders, although such aim would need to be proven.

Until the more recent succesfull offensive of pro-Assad groups (Spyer, 3 May 2013), the salafis nationalists and the global jihadis tended to be most successful militarily, seizing important locations and infrastructure, while they mobilized effectively, somehow along the lines of a “People’s War” (less the Maoist ideology).

This, in turn, prompted progressively the beginning of a change of policy regarding the delivery and type of aid given to the moderate factions by their supporting external powers. It also potentially started to soften the position of Russia, concerned by the development of jihadi terrorism, thus allowing for improvement in diplomatic talks towards negotiations, as explained by Putin in an interview with German broadcaster ARD (Ria Novosti, 5 April 2013), and as seems to be ongoing even if chaotically.

Update 8 July 2013

Aymen Jawad Al Tamimi evaluates the relationships between JAN and ISIS, where they sometimes designate the same entity, but not always, through a meticulous and thorough regional analyses:

Update 24 February 2014

The remaining part of this article is for our members and those who purchased special access plans. Make sure you get real analysis and not opinion, or, worse, fake news.

log in and access this article.

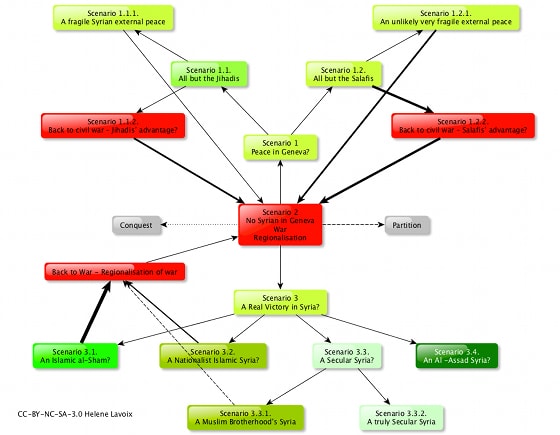

Now we have described all the actors on the Syrian battlefield. Now we shall be able to put forward a few scenarios.

————

To Scenario 1: Peace in Geneva.

——-

Detailed bibliography.

![[Victory]...depends on overwhelming striking force, 1939-1946, by S Whitear, The National Archives (United Kingdom), catalogued under document record INF3/138, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons victory, striking force, war scenario](http://www.redanalysis.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/INF3-139_War_Effort_Victory_depends_on_an_overwhelming_striking_force_Artist_S_Whitear.jpg)