The existence of climate change is now recognized as a fact, besides a few remaining climate-sceptics. Its impact is, however, very far from being systematically included in analyses, as should be done and as will be, hopefully, increasingly the norm.

The existence of climate change is now recognized as a fact, besides a few remaining climate-sceptics. Its impact is, however, very far from being systematically included in analyses, as should be done and as will be, hopefully, increasingly the norm.

A large part of the efforts related to climate change are focused on scenarios dealing with the long-term future – the end of the century – and this crucial multi-disciplinary endeavour must continue or even be reinforced. This should not, however, dispense us with looking too at the short to medium term (up to ten years) future, as climate change and its impacts are not only something that our children, grand children, and great grand children will know, but a change of context that has already started. Furthermore, those short to medium term direct and indirect impacts and the way they are faced, are most likely to have a crucial impact on our future long-term understanding and capabilities. Here, I would like to focus on the potential impacts of rising natural catastrophes on the state (government in American terms) and possible consequences.

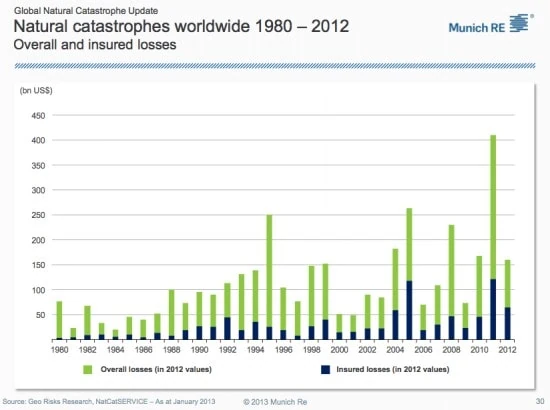

A rising number of natural catastrophes and overall losses worldwide

To be able to start considering such impacts, one must break at least two other biases. The first is inherited from the post World War II “self-determination” period, and can be caricatured as the belief that only poorer and developing countries will suffer from climate change; the main problems are first that rich countries should pay for the huge losses that poorer countries will incur, second that they should also pay for those countries that are getting rich quickly (e.g. China and India), because “the first world” polluted in the past to become rich. The second bias is that only rare, large, noticeable events matter and will impact us. Such events, e.g. Sandy, do definitely count, and furthermore may serve to raise awareness, especially when they hit a well-mediatized country, both in terms of classical media and world-wide-web coverage, such as the United States. They are, nonetheless, not the only ones, and all events must be considered (ideally, loss of biodiversity and of “ecosystem services” should also be included).

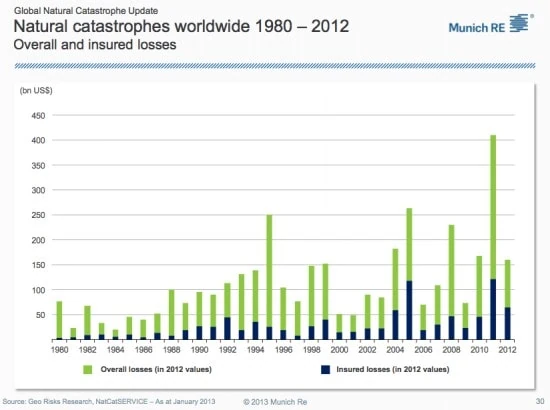

The data held and publicised by re-insurance companies are currently one of the best entry point for estimations of the past existence and costs of climate change related events. Munich-Re, notably, has “one of the world‘s largest databases on natural catastrophes” (Munich-Re, 2013: 3) and publishes regularly analyses related to natural catastrophes. If we wanted to focus solely on climate change, then geophysical events (earthquakes, volcanoes, tsunamis) should be left aside. However, the latter risks are also part of the slowly evolving conditions with which a society must deal in terms of security, notably in the Ring of Fire considering plate tectonics, as the Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami on 11 March 2011 in Japan reminded us. They should thus be kept.

In terms of geographical localization, the three world maps of natural catastrophes for 2010, 2011 and 2012 below (download from Munich-Re for full size pdf), show that, obviously, the whole world is impacted.

The breakdown by continent of all natural catastrophes between 1980 and 2012 (Munich-Re, Topics Geo 2012, 2013, pp. 54-55), in terms of number of events, fatalities and overall losses is even more telling. Monetary losses are much higher in the so-called developed world, while fatalities dramatically rise in poorer countries. Neither one nor the other is a cause for rejoicing, and the first may have bearings on the second.

The world also knows increasingly more natural catastrophes (note the longer series for the U.S., starting in 1950), as shown by the figures below, and more costly ones, the United States bearing the brunt of insured losses (Munich-Re, 2012 NatCat Year in Review).

A cost to states and governments: increased fiscal exposure

Those events have obviously a direct cost to states, as underlined in the 2013 High Risk Report of the U.S. Government Accountability Office (when this cost is usually ever hardly mentioned notably in discussions on public deficit, austerity and budgets):

“These impacts [climate change] will result in increased fiscal exposure for the federal government in many areas, including, but not limited to its role as (1) the owner or operator of extensive infrastructure such as defence facilities and federal property vulnerable to climate impacts, (2) the insurer of property and crops vulnerable to climate impacts, (3) the provider of data and technical assistance to state and local governments responsible for managing the impacts of climate change on their activities, and (4) the provider of aid in response to disasters. For example, disaster declarations have increased over recent decades, and the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) has obligated over $80 billion in federal assistance for disasters declared during fiscal years 2004 through 2011.[3] In addition, on December 7, 2012, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) within the Executive Office of the President requested $60.4 billion in federal resources for Superstorm Sandy recovery efforts to “build a more resilient Nation prepared to face both current and future challenges, including a changing climate.”

For 2012, for the U.S., Munich-Re estimates the overall (direct?) loss to US$101,13 billion, which represents 9,28% of the public deficit (US$1.089 billion). By comparison, the Watson Institute in the Costs of War project estimated the overall cost of the war in Iraq, for the U.S., at US$2,2 trillion. This would correspond to approximately US$251,43 billion per year (total cost incurred between 20 March 2003 and December 2011, i.e. 105 months). Thus, for the U.S., the estimated 2012 direct costs of natural catastrophes represent 40,22% of the estimated yearly cost of the war in Iraq. One of the major differences between both is that losses stemming from natural catastrophes will not stop but rather increase.

We must also not forget indirect costs to states in terms of loss of revenues: each catastrophe has an economic impact on all actors, from individuals to companies (as well as probably health related cost for people), which will then be translated into fewer taxes thus income for the state.

This is not only true – adapted to each state’s specificities – for all countries, but the “increased fiscal exposure” is most likely to have been going on from at least the early 1990s, if we consider Munich-Re charts. Specific research should be made to gather clearer and better knowledge. The share those supplementary costs have in so many countries’ public deficit should thus be estimated and considered.

For the future, as underlined by the U.S. G.A.O. 2013 High Risk Report, we should also add to those accumulated losses the cost of adaptive measures to climate change, expensive but necessary and cheaper than inaction (e.g. upgrading or changing infrastructures: adapting bridges, roads, buildings etc.) and of mitigating ones (carbon capture storage, changing energy mix, and all the devices we shall need to create and use).

A road to hell?

Thus, we have rising costs linked to dangers that cannot be avoided anymore. Meanwhile, policies aim at reducing state expenditures to struggle against increasing public deficit, when facing natural catastrophes obviously means rising public expenses.

In the meantime, those very dangers are most probably lowering incomes, which may only contribute to deepen the overall public deficit. This, in turn, if we remain in the same policy framework, which, among others, fails to consider fully climate change and other natural disasters, will lead to further reduction of state expenditures.

The most likely consequences, if we stay on this trajectory, are that states or governments will be increasingly unable to ensure the security of their citizens, with impact in terms of legitimacy, which, in turn, may only lead to social disorders. As a result, fatalities and casualties may only rise worldwide in all countries from unhindered impacts of disasters, civil unrest, rising criminality and reduction of aid and cooperation. We would thus be heading for a Hobbesian pre-Leviathan world, but in a harsher natural environment.

Privatization and outsourcing may not be the universal panacea, in the absence of a strong state, as respected and upheld regulatory frameworks are necessary (OECD, 2011: 18) and as impoverished people hit by multiple disasters may not be the best clients to earn profits.

Human societies may not have had to face anthropogenic environmental changes in the past, but, throughout history, they did successfully rise above the challenges of increasing costs of governance because of novel dangers. Everything being equal, these past periods could provide us with ideas regarding the solutions that must be imagined and then implemented.

Short of falling into extremely predatory authoritarian systems, where a few may survive on the despair of the many – and I recommend reading Suzanne Collins’ truly excellent novel The Hungers’ Games as an example of one of the many faces such a system could take – solutions must involve new income for political authorities to allow them ensuring security, which will most probably lead to the creation of new socio-political models of organization. In a world that seems to have lost its hope, its enthusiasm and its bearings, such a mammoth challenge could be construed as an immense rallying and mobilizing project, for those leaders with a vision.

—————

Special thanks to Dr Jean-Michel Valantin, specialised in environmental security and author of the recent Guerre et Nature (War and Nature) for many exciting discussions and for helping me overcoming information overload and finding back U.S. G.A.O. 2013 High Risk Report.

Della Croce, R., C. Kaminker and F. Stewart (2011), “The Role of Pension Funds in Financing Green Growth Initiatives”, OECD Working Papers on Finance, Insurance and Private Pensions, No. 10, OECD Publishing. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5kg58j1lwdjd-en

Munich-Re, 2012 NATURAL CATASTROPHE YEAR IN REVIEW, January 3, 2013.