The world is now struggling to know how to face the COVID-19 pandemic. We want to know how long the pandemic will last. Actually, what we want to know is when the pandemic will end and when life will be able to resume normally.

As we explained in the opening article for this series, to be able to answer these questions, considering the very high number of uncertainties involved, we need to use scenarios. Our aim is to contribute to the creation of robust scenarios in our field, political science and international relations. We are thus concerned with the future of polities, i.e. the futures of organised societies. Nonetheless, to be able to do so, we obviously have to take into account what other sciences, those primarily concerned with diseases and pandemics, find out.

For now we are trying to establish both the general structure for our scenario tree and the timeframe. Thus we study main critical factors that will allow us to articulate our scenarios.

In this article, we first briefly summarise the points made in previous articles. We then turn to the antiviral prophylaxis and treatment as a second key critical factor.

Summary of previous findings

Objectives of societies faced with a pandemic

Because we have collectively and individually “chosen” not to accept the baseline worst case scenario, then our main aim is now survival for each individual, and for each polity, society or country. Fundamentally, as long as the pandemic continues, thus as long as the baseline worst case scenario could become a reality, each polity will need to fulfil simultaneously two objectives.

First objective

Covid-19 pandemic is available for free.

Please consider becoming a member of the Red (Team) Analysis Society

to support independent and in-depth analysis or

Fund Analysis on the COVID-19 with a donation

The first objective is to reduce as much as possible the fatalities resulting from the disease. This implies reducing the number of infected people and caring for those who are ill. This means, in turn, not overwhelming the care system.

Should we fail, then, not only the dreaded scenario we seek to avoid would take place, but, at worst, all other fatalities and deaths we succeeded to prevent over centuries could come back. The excess deaths (compared with the pre-pandemic time) would be dramatic. It would also seriously impaire the capacity of a society to ensure its security and, at term its survival.

Second objective

The second objective is to continue having a society that ensures fundamental security.

Simultaneous objectives

The two aims must be fulfilled at the same time.

Indeed, if fundamental security is not ensured, then the system will rapidly collapse. Neither caring for diseased people, nor containment measures will be possible anymore. The pandemic will run its course as with the worst case scenario, but the situation will be even worse. If we do not stop the pandemic, then death and disease will take their toll and damage the capacity of society to ensure its security. Society will be fragilised, and in turn will less be able to handle the pandemic, increasing fatalities. We risk here to fall into a vicious circle.

Immunisation and vaccine as a first key critical factor

We explained in the previous article, that immunisation through vaccination is a first critical factor around which we can organise the architecture of our scenarios. We also assessed – with many uncertainties remaining – that we could not expect such immunisation to take place before winter 2022-2023. This gives us a first broad likely scenario upon which we can concentrate. Within this scenario that we shall use as framework, we need to understand the futures of our systems as they face the COVID-19 over the next two to three years.

Actually, another implicit scenario at the same level of analysis should also be made explicit. This scenario is, however, uncontrollable, according to the current and expected stage of knowledge. The virus, could lose either its infectious power or its lethality or a strong immunity could also develop naturally among human beings. In that case, the pandemic would end much earlier. This scenario being less likely and also obviously less threatening, considering limited resources, we shall not, right now, examine it. Nonetheless the factors influencing the probability of this scenario must be monitored.

Antiviral prophylaxis and treatment – a second key critical factor

Antiviral prophylaxis and treatment are a second critical factor for our scenarios architecture. Indeed, we try to reduce fatality. Thus, if we have a cure for the disease, the possibility of the worst case baseline scenario disappears.

To date, 30 March 2020, there is no known antiviral treatment against the SARS-CoV-2, i.e. certain and having gone through all the usual testing process.

Thus, some of the key questions we must ask are as follows. Is it possible to see a treatment discovered and developed? Which types of effects this treatment could have on the disease and on the pandemic? When could this treatment become available?

Here, we face a supplementary challenge as controversies, debates, power and ego-struggles have entered the field. Meanwhile, notably out of fear, panic, or lack of trust in governments, these debates and struggles have been transformed and relayed as rumours, fake news, and conspiracy theories.

As far as we are concerned, we shall rely on scientific papers and focus on looking for elements which are key for our aim, contributing to establish valid scenarios. We shall also keep the issue of the timeframe in mind.

Possible candidate antiviral treatments from existing and known drugs

The Chloroquine hope and debate

Since mid-February and increasingly so as the pandemic spread, the efficiency of chloroquine, either as Chloroquine phosphate or as one of Chloroquine’s derivate, hydroxychloroquine, to treat patients infected with the SARS-CoV-2, has become a hot topic in scientific and lay publications (see a non-exhaustive bibliography below). Some promote it as the Graal that will save us all from the disease. Others just underline that the necessary clinical tests allowing to assert and measure its efficiency – as well as the ideal posology according to the stage of the disease – have not yet been completed. Meanwhile, conspiracy theories abound.

Hope from a Chinese publication

In a nutshell, the issue is relatively simple. On 19 February 2020, as an e-publication, Gao J, Tian Z, Yang X, published a letter for advanced publication titled “Breakthrough: Chloroquine phosphate has shown apparent efficacy in treatment of COVID-19 associated pneumonia in

clinical studies” in the journal BioScience Trends. There, they notably stated that

“The drug is recommended to be included in the next version of the Guidelines for the Prevention, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Pneumonia Caused by COVID-19 issued by the National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China for treatment of COVID-19 infection in larger populations in the future.”

They also underlined that

“results from more than 100 patients have demonstrated that chloroquine phosphate is superior to the control treatment in inhibiting the exacerbation of pneumonia, improving lung imaging findings, promoting a virus negative conversion, and shortening the disease course according to the news briefing”.

The need for further trials

Now, those who urge caution do so because they would like to have access to all these trials and to be able to replicate and enlarge them.

Consequently, up to 30 March 2020, at least 17 studies (out of 22 trials) have started, or are planned, to carry out further testing of the efficiency of hydroxychloroquine on patients with COVID-19. They are taking place from South Korea to the U.S. through Thailand, Brazil and the EU. They address various stages of the clinical trials studying a drug. One of these studies only has been completed, in Shanghai. Its results have been published in the Journal of Zhejiang University (Medical Sciences, 3 March 2020). It was carried out only on 30 patients.

Disappointing results on a small sample

We should note that the results of the Shanghai’s trial show no impact of hydroxychloroquine on patients, compared with the control group. Even worse, although on such a small group conclusions are only tentative, one patient under hydroxychloroquine developed to a severe condition (ibid).

A French microbiologist promotes the treatment

Meanwhile, some French immunologists and specialists in microbiology headed by the Director of the State Institut Hospitalo-Universitaire Méditerranée (IHM) Infection Didier Raoult promoted the early use of Chloroquine (Philippe Colson , et al., “Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine as available weapons to fight COVID-19”, International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents, 26 February 2020). Furthermore, the same team tested Chloroquine with Azythromycine on 26 patients, 16 others being used as control group (Gautret et al. (2020) Hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin as a treatment of COVID‐19: results of an open‐label non‐randomized clinical trial). On 22 March 2020, they decided to start applying hydroxychloroquine massively to infected people in Marseille, adding furthermore Azythromycine.

Out of the 17 studies mentioned earlier, three of them test the combination of Hydroxychloroquine and Azythromycin.

Further need to be careful

Meanwhile, scientists, including from the IHM, have warned about the difference between in vitro successful experiments and in vivo ones. For example, Franck Touret et Xavier de Lamballerie in “Of chloroquine and COVID-19” (Antiviral Research 177 (2020) 104762) pointed out various negative possible impacts in previous attempts at using Chloroquine on other types of viruses. Notably, “in a nonhuman primate model of CHIKV infection”, the use of Chloroquine was shown to delay the cellular immune response (Ibid.). Even though every virus is different, these earlier trials on other viruses highlight the need for caution.

An indication from outside the medical world

To this, we should add an indication coming from outside the world of clinical tests. If China considers “the apparent efficacy” of Chloroquine since 19 February, it has nonetheless continued its lockdown, travel bans and quarantine policy on the country. Indeed, for example, lockdown on Wuhan will be partially lifted only on 8 April 2020 (BBC News, “Coronavirus: Wuhan to ease lockdown as world battles pandemic“, 24 March 2020). Furthermore, China is rightly being extra careful with not allowing new imported cases to spread (BBC News, “Coronavirus travel: China bars foreign visitors as imported cases rise“, 27 March 2020). It is paying particular attention to all cases, in case a new wave of COVID-19 would hit the country (Ibid).

Should Chloroquine – possibly added to Azythromycine – be such a miracle drug, then China would not be so afraid of seeing a new epidemic outbreak. Thus, if we take Chinese policies and behaviour as indication, Chloroquine could hopefully alleviate sufferings, but not critically change the disease behaviour.

The results of the clinical trials will tell.

Other candidate treatments

Meanwhile, China and other countries are testing other drugs and molecules, such as arbidol, remdesivir, favipiravir, lopinavir and ritonavir, also with immunomodulator interferon beta-1b and others (Liying Dong, Shasha Hu, Jianjun Gao, Discovering drugs to treat coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), Drug Discov Ther. 2020;14(1):58-60. doi: 10.5582/ddt.2020.01012; Lindsey R. Baden, M.D., and Eric J. Rubin, M.D., Ph.D., Covid-19 — The Search for Effective Therapy, NEJM, 18 March 2020; Camille Gaubert, “Coronavirus : lancement d’un essai clinique sur 3.200 patients atteints de Covid-19“, Sciences et Avenir, 12 March 2020; John Cahill, “Potential COVID-19 therapeutics currently in development“, European Pharmaceutical Review, 26 March).

Major ongoing trials

Among all these candidates the WHO has selected four treatments as most promising for a very large trial: the “experimental antiviral compound called remdesivir; the malaria medications chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine; a combination of two HIV drugs, lopinavir and ritonavir; and that same combination plus interferon-beta” (Kai Kupferschmidt, Jon Cohen, “WHO launches global megatrial of the four most promising coronavirus treatments“, Science, 22 March 2020). The WHO solidarity trial is expected to run from March 2020 to March 2021 (ISRCTN registry).

The French INSERM coordinates a European corresponding trial called DISCOVERY on 3200 patients. It started on 22 March. Fifteen days after the inclusion of each patient, the analysis of treatment efficacy and safety will be evaluated.

We should also count the Institut Hospitalo-Universitaire Méditerranée 22 March beginning of treatment of patients with Chloroquine and Azythromycine also as a trial. Indeed, it differs from SOLIDARITY and DISCOVERY because it adds Azithromycine. This point could be important if we consider the pre-test done, as Azythromycine seemed to have a critical role to play (Ibid.).

As highlighted above, according to the database Clinicaltrials.gov of the U.S. government, 22 trials are currently taking place on various drugs.

Discovering new treatments or uncovering less common treatments

This type of scenario is quite similar, in terms of process, to what we saw with vaccines. We must first discover or unearth one or more molecules that may positively impact the development of the disease, yet without adverse effects.

Artificial Intelligence, Automation, and supercomputers against the SARS-CoV-2

As existing and known drugs and treatments are tried, researchers are also also busy trying to unearth or discover molecules that could help fight the SARS-CoV-2.

For example the Institut Pasteur of Lille – France (EN version) tests molecules on the virus thanks to robots in a specially confined laboratory. As a result, researchers can greatly speed the rhythm of tests. Thousands are carried out daily. Meanwhile, the combination of molecules by pairs for testing is also automated (website).

DeepMind, or rather DeepMind Technologies Limited, the famous artificial intelligence / deep learning lab. Alphabet Inc. (Google) bought, joined the efforts to fight the SARS-CoV-2 ( Computational predictions of protein structures associated with COVID-19, 5 March 2020 – for more on artificial intelligence and deep learning see our related series). It used the latest version of their AlphaFold system to “release structure predictions of several under-studied proteins associated with SARS-CoV-2”. Should these deep learning predictions then be confirmed through experiments, then they will have contributed to a better knowledge of the virus and possibly to the development of new drugs.

Researchers at the U.S. Oak Ridge National Lab (Department of Energy) use Summit, the most powerful supercomputer to date, “to run through a database of existing drug compounds to see which combinations might prevent cell infection of COVID-19” (Brandi Vincent, “Researchers at Oak Ridge National Lab Tap into Supercomputing to Help Combat Coronavirus“, Nextgov.com, 11 March 2020). Researchers could simulate 8,000 compounds and select 77 that have “the potential to impair COVID-19’s ability to dock with and infect host cells” (Dave Turek, “US Dept of Energy Brings the World’s Most Powerful Supercomputer, the IBM POWER9-based Summit, Into the Fight Against COVID-19“, IBM News Room, nd). It took them a couple of days instead of “months on a normal computer” (Ibid.).

As we pointed out in our series on supercomputers and computing power, these are increasingly key factors for the present and the future. In this case, supercomputers could be critical in the fight against this pandemic.

Other efforts using supercomputing power, such as a NSF programme or the European program Exscalate4CoV are at work (Oliver Peckham, “Global Supercomputing Is Mobilizing Against COVID-19“, 12 March 2020, HPC Wire). For example,

“E4C is operating through Exscalate, a supercomputing platform that uses a chemical library of over 500 billion molecules to conduct pathogen research. Specifically, E4C is aiming to identify candidate molecules for drugs, help design a biochemical and cellular screening test, identify key genomic regions in COVID-19 and more”.

Oliver Peckham, “Global Supercomputing Is Mobilizing Against COVID-19“, 12 March 2020, HPC Wire

We could also imagine that companies and start-ups in the quantum information science field, who highlighted the importance of quantum computing and simulation in the field of chemistry, for example, or material science, would be actively contributing to the fight against the COVID-19 (e.g. Foreseeing the Future Quantum-Artificial Intelligence World and Geopolitics; Quantum Optimization and the Future of Government). A similar point could be made regarding logistics necessary to survive the pandemics, working from the Volkswagen Group research with D-Wave (Quantum Optimization, Ibid.). Yet, up to 30 March 2020, no open source information regarding the participation of the “quantum world” in the fight against the COVID-19 seems to be available.

When could such a new treatment become available?

There is no way to know how close we are to the discovery of the right molecule or combination of molecules.

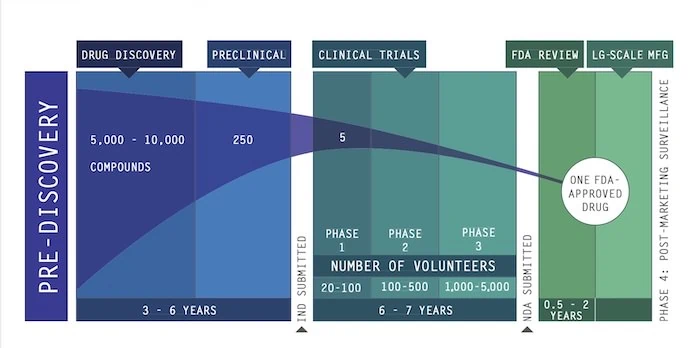

Once it is discovered, the new potential drug will have to go through the whole process of trial and development, including clinical trials (e.g. EU Drug Discovery and Development, U.S. Biopharmaceutical Research & Development).

Classically – i.e. when we are not in an emergency mode – this process takes 10 to 15 years (Drug discovery, Ibid.) as shown in the picture below.

Then, even if we are lucky and manage to shorten the process – to how long? – we shall still need to manufacture the drug and then deliver it.

First, this explains why the current focus is on known drugs. Second, this highlights that totally new drugs may not help us on the short and even medium term.

This reminds us that major world pandemics, in the past, lasted not months, but years. Meanwhile, outbreaks happened across centuries. If ever, for antiviral treatments, hope is only in the discovery of a totally new medicine, then then waiting (actively) for a vaccine moved from being a pessimistic scenario to being an optimistic scenario.

Key elements to look for in an anti SARS-CoV-2 treatment and to inject in scenarios

Because an antiviral treatment can mix different drugs, posologies and approaches, sub-scenarios will need to include main elements impacting epidemiological models. To identify them, we used the model of the Imperial College COVID-19 Response Team in Impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) to reduce COVID19 mortality and healthcare demand, 16 March 2020. As a result, we shall also get the indicators we need to monitor candidate treatments.

We assume that, once a treatment is found, epidemiologists will relatively rapidly run their models and publish results. In turn, this will allow us updating our scenarios as well as their likelihoods.

The key elements to which we need to pay attention are as follows.

Impact on infectiousness

For example, the treatment could be given prophylactically to everyone, or to the contact cases of an infected person. In turn, the treatment could also lower the cases of asymptomatic or very mild symptomatic infections.

Impact on immunity

The impact of treatment on immunity after recovery from infection, on the short term and on the long-term needs to be evaluated.

Impact on severity of disease

If the treatment is given to symptomatic cases, we shall monitor if the treatment lowers the amount of patients developing severe, critical and fatal disease. This could twice decrease the pressure on the health system. Indeed, we would have less patients needing stays in hospitals. Furthermore, the duration of the stay in hospital could also diminish. Currently, the Imperial College COVID-19 Response Team estimates that we have:

“A total duration of stay in hospital of 8 days if critical care is not required and 16 days (with 10 days in ICU) if critical care is required. With 30% of hospitalised cases requiring critical care, we obtain an overall mean duration of hospitalisation of 10.4 days…”

Imperial College COVID-19 Response Team, Impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) to reduce COVID19 mortality and healthcare demand, 16 March 2020

Manufacturing and supply

Again, as for vaccine, the manufacturing of doses and their availability per country will need to be envisioned in detailed scenarios. Supply tensions are likely to emerge. As a result, we may possibly face international tensions. Should the quantity of the new drug be insufficient per country, then it would be interesting if epidemiological models were run according to possible supply.

New treatment(s) against the SARS-CoV-2 could offer any combination of the proprieties above. Ideally, epidemiological models or those built on them would also account for the feedbacks between non-pharmaceutical interventions, new treatments beneficial impacts and drug availability.

With the next articles, we shall continue to explore the factors that determine the architecture of our scenarios.

Bibliography

Tara Haelle, “Chloroquine Use For COVID-19 Shows No Benefit In First Small—But Limited—Controlled Trial“, Forbes, 25 marche 2020.

Tony Y. Hu, Matthew Frieman & Joy Wolfram, “Insights from nanomedicine into chloroquine efficacy against COVID-19“, Nature, 23 March 2020.

Xueting Yao, Fei Ye, Miao Zhang, Cheng Cui, Baoying Huang, Peihua Niu, Xu Liu, Li Zhao, Erdan Dong, Chunli Song, Siyan Zhan, Roujian Lu, Haiyan Li, Wenjie Tan, Dongyang Liu, In Vitro Antiviral Activity and Projection of Optimized Dosing Design of Hydroxychloroquine for the Treatment of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), Clinical Infectious Diseases, , ciaa237, https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa237

Adam Rogers, Chloroquine May Fight Covid-19—and Silicon Valley’s Into It, Wire, 19 March 2020.

Liu, J., Cao, R., Xu, M. et al. Hydroxychloroquine, a less toxic derivative of chloroquine, is effective in inhibiting SARS-CoV-2 infection in vitro. Nature, Cell Discov 6, 16 (2020), 18 March 2020. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41421-020-0156-0

Philippe Colson, Jean-Marc Rolain, Jean-Christophe Lagier, Philippe Brouqui, Didier Raoult, “Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine as available weapons to fight COVID-19“, International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents (2020), doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105932

Gautret et al. (2020) Hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin as a treatment of COVID‐19: results of an open‐label non‐randomized clinical trial. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents – In Press 17 March 2020 – DOI : 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105949.

Guangdong Provincial Department of Science and Technology and Guangdong Provincial Health Committee Multi-center Collaborative Group on Chloroquine Phosphate for New Coronavirus Pneumonia, “Expert Consensus on Chloroquine Phosphate for New Coronavirus Pneumonia” [J]. Chinese Journal of Tuberculosis and Respiratory Medicine, 2020,43 (03 ): 185-188. DOI: 10.3760 / cma.j.issn.1001-0939.2020.03.009

Featured image: Image by Darko Stojanovic from Pixabay